Washington: Throughout January, the World Health Organization publicly praised China for what it called a speedy response to the new coronavirus.

It repeatedly thanked the Chinese government for sharing the genetic map of the virus ‘immediately’, and said its work and commitment to transparency were ‘very impressive, and beyond words’.

But behind the scenes, it was a much different story, one of significant delays by China and considerable frustration among WHO officials over not getting the information they needed to fight the spread of the deadly virus, The Associated Press has found.

Despite the plaudits, China in fact sat on releasing the genetic map, or genome, of the virus for more than a week after three different government labs had fully decoded the information.

Tight controls on information and competition within the Chinese public health system were to blame, according to dozens of interviews and internal documents.

Chinese government labs only released the genome after another lab published it ahead of authorities on a virologist website January 11.

Even then, China stalled for at least two weeks more on providing WHO with detailed data on patients and cases, according to recordings of internal meetings held by the U.N. health agency through January — all at a time when the outbreak arguably might have been dramatically slowed.

WHO officials were lauding China in public because they wanted to coax more information out of the government, the recordings obtained by the AP suggest.

Privately, they complained in meetings the week of Jan. 6 that China was not sharing enough data to assess how effectively the virus spread between people or what risk it posed to the rest of the world, costing valuable time.

“We’re going on very minimal information,” said American epidemiologist Maria Van Kerkhove, now WHO’s technical lead for COVID-19, in one internal meeting.

“It’s clearly not enough for you to do proper planning.” “We’re currently at the stage where yes, they’re giving it to us 15 minutes before it appears on CCTV,” said WHO’s top official in China, Dr. Gauden Galea, referring to the state-owned China Central Television, in another meeting.

The story behind the early response to the virus comes at a time when the U.N. health agency is under siege, and has agreed to an independent probe of how the pandemic was handled globally. After repeatedly praising the Chinese response early on, U.S. President Donald Trump has blasted WHO in recent weeks for allegedly colluding with China to hide the extent of the coronavirus crisis.

He cut ties with the organisation on Friday, jeopardizing the approximately USD 450 million the U.S. gives every year as WHO’s biggest single donor.

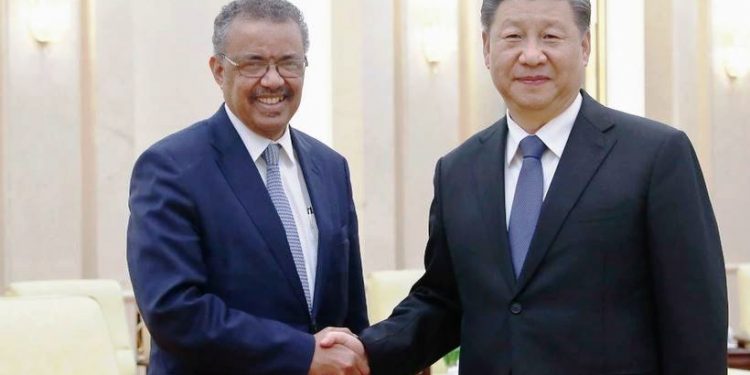

In the meantime, Chinese President Xi Jinping has vowed to pitch in $2 billion over the next two years to fight the coronavirus, saying China has always provided information to WHO and the world “in a most timely fashion.”

The new information does not support the narrative of either the U.S. or China, but instead portrays an agency now stuck in the middle that was urgently trying to solicit more data despite limited authority.

Although international law obliges countries to report information to WHO that could have an impact on public health, the U.N. agency has no enforcement powers and cannot independently investigate epidemics within countries. Instead, it must rely on the cooperation of member states.

The recordings suggest that rather than colluding with China, as Trump declared, WHO was itself kept in the dark as China gave it the minimal information required by law. However, the agency did try to portray China in the best light, likely as a means to secure more information.

And WHO experts genuinely thought Chinese scientists had done “a very good job” in detecting and decoding the virus, despite the lack of transparency from Chinese officials.

WHO staffers debated how to press China for gene sequences and detailed patient data without angering authorities, worried about losing access and getting Chinese scientists into trouble. Under international law, WHO is required to quickly share information and alerts with member countries about an evolving crisis.

Galea noted WHO could not indulge China’s wish to sign off on information before telling other countries because “that is not respectful of our responsibilities.”

In the second week of January, WHO’s chief of emergencies, Dr. Michael Ryan, told colleagues it was time to ‘shift gears’ and apply more pressure on China, fearing a repeat of the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome that started in China in 2002 and killed nearly 800 people worldwide.

“This is exactly the same scenario, endlessly trying to get updates from China about what was going on,” he said. “WHO barely got out of that one with its neck intact given the issues that arose around transparency in southern China.”

Ryan said the best way to ‘protect China’ from possible action by other countries was for WHO to do its own independent analysis with data from the Chinese government on whether the virus could easily spread between people. Ryan also noted that China was not cooperating in the same way some other countries had in the past.

“This would not happen in Congo and did not happen in Congo and other places,” he said, probably referring to the Ebola outbreak that began there in 2018.

AP