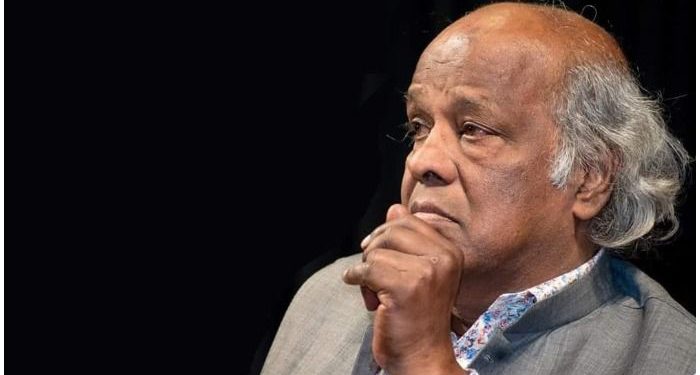

Saeed Naqvi

Rahat Indori was five years old when the much loved poet Majaz died of a stroke after he was found on the freezing terrace of a country liquor shop in Lucknow’s Qaisar Bagh. As someone born to a poor cloth mill labourer, Rahat’s nightmare of financial insecurity only increased watching the economically circumscribed lives of Urdu poets. Majaz was only one of them.

Rahat worked hard educating himself right upto PhD on a subject which was to stand him in good stead in subsequent years – Urdu Mushaira. And what a performer he became in Mushairas – charging upto `10 lakh for an appearance – quite unprecedented.

A brief digression might help explain the phenomenon of Rahat Indori, the Urdu poet who died in his hometown, at the age of 70 last week. Govind Ballabh Pant, Uttar Pradesh’s first Chief Minister and Union Home Minister died on the same day as one of Urdu’s greatest ghazal writers of the 20th Century, Jigar Moradabadi. But while Pant made banner headlines in newspapers, Jigar received a single column notice, buried in the inside page.

This is precisely the reason why Rahat’s dominance of the media space following his death is such a phenomenon. Andy Warhol’s observation is succinct: society has reached a point where everybody will have fifteen minutes of fame. But applying this quip to Rahat Indori would be an insult. Rahat had an extraordinary following for decades.

Rahat missed out on any personal experience of the greats like Faani Badayuni, Jigar Moradabadi and Yaas Yagana Changezi. He was too young. But Josh Malihabaid and Firaq Gorakhpuri were around till the late 80s, and a 30-year-old budding poet of Indore must have overlapped in a Mushaira or two.

Firaq, of course, taught English literature in Allahabad University, but Josh mostly depended on feudal patronage after the abolition of Zamindari system in 1952. Some experiences for a man of his ego were humiliating. For instance, when Josh was introduced to the Patiala Durbar, the state’s Prime Minister Sardar KM Panikkar, ill-equipped to place any value on an Urdu poet, decided on a stipend of `75 per month. The Maharaja, an admirer of Josh, was embarrassed: he increased the amount to `300, a princely sum those days.

The fastidious would not rank Rahat among the finest poets, but the poets who would qualify for their esteem would never have audiences of thousands in their thrall, Mushaira after Mushaira, across India, indeed, worldwide.

What will be Rahat’s place in literature? There is a singular lack of endorsement of a large swathe of contemporary Urdu poetry by critics, scholars, connoisseurs and those who have grown in an informed Urdu milieu. Ironically, this turns out to be in inverse proportion to the unprecedented popularity of poets like Rahat. How does one explain this equation?

It is almost axiomatic that with rising egalitarianism a taste for classics will decline. This truism was advanced for classical music too. It was a touching dependence on feudal patronage, as Jawed Naqvi recently reminded us, that caused the great Sarod maestro, Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan (Amjad Ali Khan’s father) to refuse any recording of his performances: “I don’t want my music to be played in city squares and paan shops.”

The danger of feudal patronage drying up was real but mostly in North India. The South remains much the more civilized thanks to such institutionalized treats in dance and music annually as “The Season” in Chennai. In the Hindi belt, just as the feudal patronage tapered off, enlightened business houses like the Bharatrams, Charatrams and the Sarabhais stepped in massively. They have now been superseded by the unbelievable explosion of music on the social media. Everything, from the earliest recordings in 1900, is available with the flip of a switch.

Compared to music, the graph of Urdu poetry is more complex. After Partition, it was assumed that interest in Urdu would decline. Josh Malihabadi’s dictum that “a language which does not give you bread will die” did operate to the extent that the number of scholars, critics, indeed even university faculties dwindled.

A more formal and educated appreciation of poetry was a distinct casualty. Highbrow literature did begin to make way for more popular genres. But Urdu was able to frequently shock those who had written its obituary. Never was this shock more telling than during the unprecedented success of Jashn-e-Rekhta, a celebration of Urdu in all its forms, an annual carnival which fills up half a dozen venues at New Delhi’s National Stadium day and night for three days.

This brainchild of a remarkable cultural entrepreneur Sanjiv Saraf is an unparalleled contribution towards uplifting the drooping morale of Urduwallas. Urdu’s demise, in any case, was prematurely predicted after the resilience it had demonstrated in the Hindi film industry in the field of lyrics, diction, dialogues both, their content and delivery. Little wonder, Rahat became a sought after lyricist with music directors like Anu Malik and AR Rahman.

Artist M.F. Hussain became one of Rahat’s obsessive admirers after watching him keep a packed hall spellbound during a poetic symposium in Qatar. They became close friends. In fact the cover of one of Rahat’s collections, has been designed by Hussain. There is stunning irony about his death. Rahat wrote:

“Waba phaili hui hai har taraf/ Abhi mahaul mar jaane ka naheen.”(A pandemic is spreading everywhere/This is not the proper season to die.)

The poet who wrote these lines is declared Corona positive on the night of August 10 and is dead by August 11. Is there a galloping strain of Corona?

Remember how Habib Jalib’s “Main naheen manta” became an iconic song during the anti-citizenship stir? Equally evocative and direct was Rahat’s couplet:

“Sabhi ka khoon hai shamil yahan ki mitti mein; Kisi ke baap ka Hindostan thodi hai”(The blood of all of us has mingled in this soil; Hindostan is not the property of anybody’s father).

IANS