In RK Narayan’s The Doctor’s Word, Dr. Raman, the titular doctor of the story, finds himself in a dilemma. Gopal, his dear friend of many decades, is sick and bedridden. After visiting Gopal, Raman, who has a reputation for always being truthful, concludes that his friend is counting his last breaths, and if he lets him know the true diagnosis, the man will lose whatever hope he has left. The doctor, for once in his life, decides to lie. He tells Gopal that he has a long life ahead of him. In the coming days, unexpectedly, Gopal recovers, and survives, leaving Raman in awe of the unknown power his words hold.

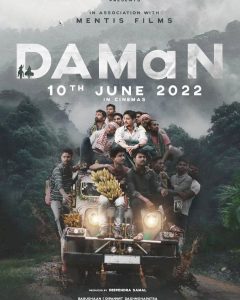

Babushaan’s Siddharth, a physician, in the recently released Odia film DAMaN, also comes to terms with this power, the power of his words. Securing a medical degree from a city college, he has no intention of serving in the countryside. But fate has other plans. He is posted at a primary health centre (Janbai) of Malkangiri, a collection of some 151 human settlements that is known as the cut-off area, because water separated it from the mainland.

Siddharth, used to the glitz of city life, 24X7 power supply and running water, is out of his comfort zone. In the new place, after spending only a night in the company of buzzing mosquitoes, he is ready with his bags packed, to return to the city.

But again, fate intervenes. As his boat is about to leave, a man begs for help with his shivering daughter in arms. Siddharth, hesitantly, turns back, examines the patient, as his boat leaves. Finding that she is down with malaria, he administers her treatment, and scolds the father for being so late in coming to the hospital. There, Ravi Muduli, the pharmacist, played by a charming Dipanwit Dasmohapatra, tells Siddharth, that the people here believe in ghosts, and when they get fever, they go to the ‘dishari’( exorcist), which, predictably, leads many to their graves. But there is a chance; they might listen to his words, because, after all, he is a doctor, says the pharmacist. Ravi’s optimism coupled with a few slogans written on hospital walls propels Siddharth to begin a new journey.

Actor Babushaan, who early in his career got pigeonholed into playing the cute and funny boy in love, wins hearts this time demonstrating his variability mostly through facial expressions

The plot aside, Daman works remarkably well as a film. It’s a splash of rain in the desert of originality that is Odia cinema. All the elements of filmmaking come together nicely.

Pratap Rout’s cinematography helps set the proper atmosphere. The clouds over the mountains, the green valleys and the forests, evoke the present promise of an adventure. The landscape shots remind one of Denis Villenueve’s Sicario (2015), that feeling of immersion in the geography of a film.

The sound design by Gaurav Anand complements the narrative. The use of traditional folk instruments amplifies the atmospheric dimension of the film. The lyrics to the songs reflect the state of mind of the lead character, his predicament, at times, his doubts, helplessness, and resolve.

The actors, many of them local stage artistes, bring an aura of authenticity with their presence. Babushaan, who early in his career got pigeonholed into playing the cute and funny boy in love, demonstrates here his acting range with subtlety.

Whatever may be DaMAN’s limitations, they seem small in comparison to the acceptance it has received

Moreover, there is something to admire about the simplicity of the plot. The film is basically about the success of a public welfare scheme, which seems quite a boring premise for a film. But the directors, Vishal Mourya and Debi Prasad Lenka, turn it interesting by using the tool of the character arc. It becomes a ‘rite-of-passage story’ for a young doctor, who undergoes a character transformation and learns to accept his social responsibilities.

Also noteworthy is the discipline of the filmmakers. Walking into the film I half expected the lead character, an outsider in a new place, the pardesi babu, to fall in love with a local girl and go on to fight the naxalites and build dams and cry to the tunes of yeh jo desh hai tera… But the directors, to their credit, abstain from doing any of that, from making it another Swades (2004).

However, Daman’s strengths could also be seen as its weaknesses. There are no other plotlines except for the central one, that’s why the latter half feels less dramatic. And by telling the story as the journey of a single character the film risks becoming a story of a saviour, of an educated outsider putting an end to the suffering of an underprivileged group.

Whatever may be its limitations, they seem small in comparison to the acceptance it has received. Till the writing of this review, the movie was running to packed houses in most centres of Odisha and on public demand, more prints were on the way for screening in other cities like Kolkata, Mumbai, Bangalore and Ahmedabad. The success of Daman, and those of TV shows like Panchayat and films like Kantara (2022), only proves that the next batch of good stories is going to come from filmmakers who go to the ground, listen to the people, the folktales and mine the collective memory.