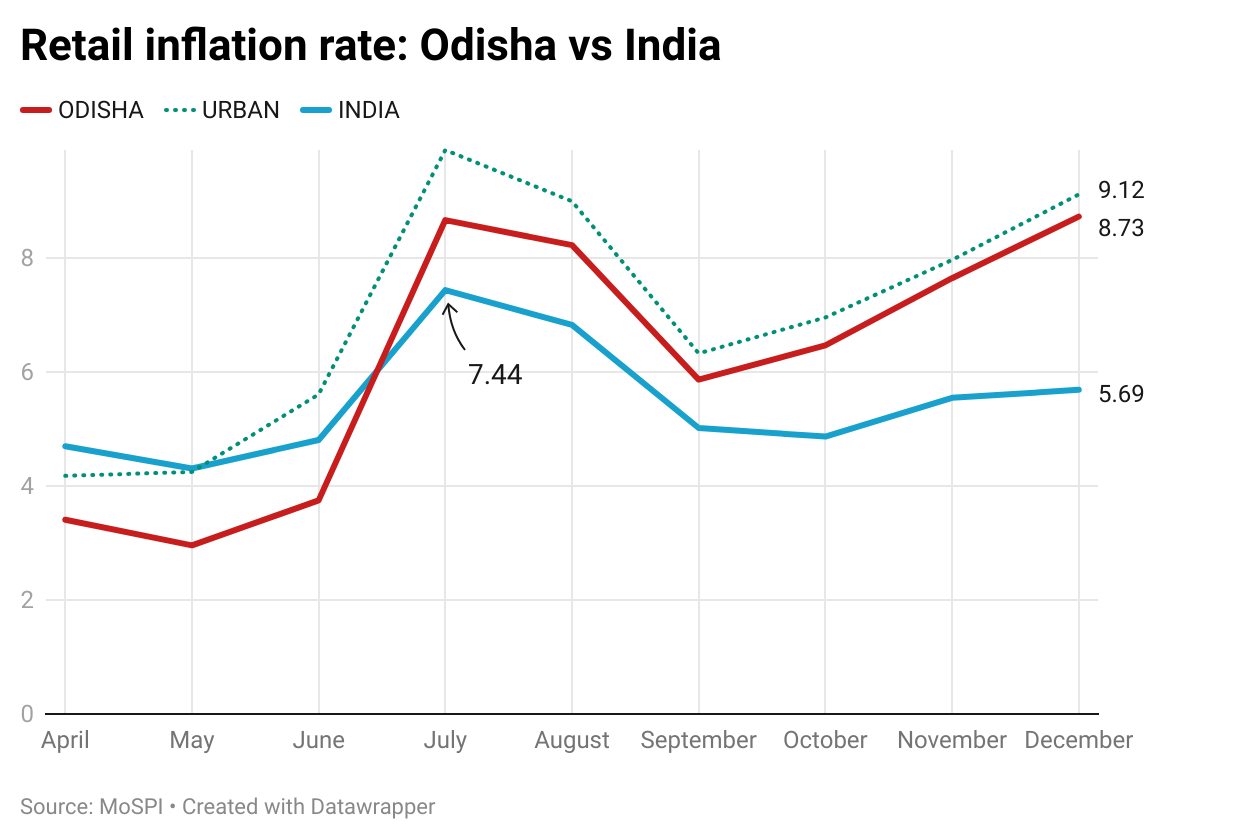

The recently released retail inflation data by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (MoSPI) for December 2023 showed Odisha recording the highest inflation rate among all states and Union Territories of the country. The trend didn’t come as a surprise given the state had been posting the country’s highest inflation rate for the last two months. And, in the last six months, the second half of 2023, inflation in the eastern Indian state had remained high – above the national level. (Chart 1) Inflation rate, calculated from the Consumer Price Index (CPI), captures how the price of a basket of goods and services changes over a period of time, generally on a year-on-year basis. The Reserve Bank of India has a mandate to keep the rate within 4 per cent, with a maximum legroom of 6 per cent.

In 2023, though the all India level inflation rate went above the 6 per cent margin in July (7.44), it fell back to 5.02 in September. But for Odisha, the rate shot up from 3.75 per cent in June to 8.67 in July, and continues to remain above the 6 per cent mark, except for a brief climb down in September. For consumers in the state, this has meant rapid rise in daily goods’ prices.

In April, OMFED hiked price of packaged milk by Rs 4 per litre, citing rise in packaging, logistics and cattle feed cost. In July, tomato prices in the Capital jumped to Rs 200 per kg, while prices of other vegetables like brinjals and pumpkins went up by 20 to 30 rupees. Later in October, because of inadequate supply from Andhra Pradesh, onion prices doubled within a couple of weeks from Rs 30 to Rs 60. The inflation at the national level has mainly been driven by rise in price of pulses, spices, fruits and vegetables. Explaining high inflation in Odisha, economist Amarendra Das of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the National Institute of Science Education and Research (NISER) says, “El nino could have affected the vegetable production.

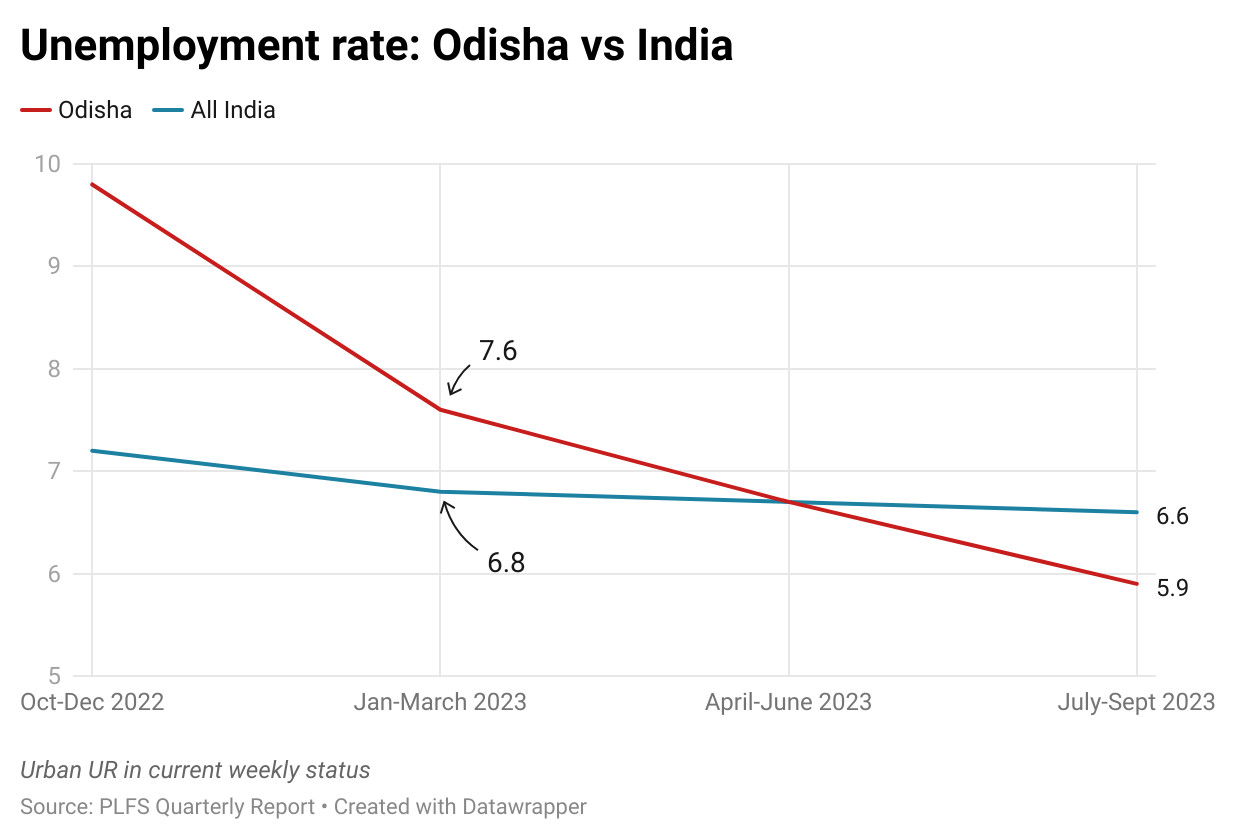

Since Odisha imports all pulses, edible oil and vegetables from other states, it could have kept the inflation rates higher compared to other states.” Das adds that there could also be a ‘low-base effect,’ where a small absolute change from a low initial amount, when converted into percentage, looks large. Like, a change of 20 from an initial amount of 100, a lower base, would be 20 per cent change, whereas a change of 20 from 200, a higher base, would be 10 per cent. “Odisha’s base was lower in the last two years compared to other states. So, the same amount of price rise in all states will be higher in percentage terms for Odisha,” he says. Contrary to other states, where rural inflation is often higher than urban, in Odisha inflation rate has remained consistently higher in urban areas, possibly due to rapid urbanisation. However, with rising inflation, the unemployment rate in urban areas has decreased, as economists have often observed an inverse relationship between the two.

According to data from the quarterly Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) urban unemployment rate has fallen down from 7.6 per cent in January March 2023 to 5.9 in July September. (Chart 2) “Price rise is something we have gotten used to. But it always hits harder people who have private jobs. Government employees get dearness allowances, but we don’t get timely salary increments. The only option we have is to change jobs, which is now an annual hassle,” said Amaresh Mohanty who works as a sales agent in a private firm. But ripple effect of the price rise has spread well beyond the job market, even into the modest household kitchen. “Our monthly grocery bill has now gone past Rs 5,000. With schools and tuition also hiking their fees, we face the dilemma every month whether to send our kids to tuition or to serve them healthy meals,” said Rashmirekha Swain, a housewife.