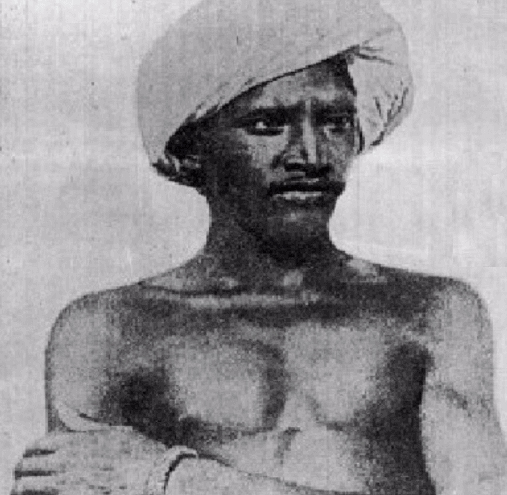

Debendra Kumar Biswal

Thursday, November 15, is the birth anniversary of Birsa Munda (1875-1900), known as Dharti Abba or Bhagwan among adivasis of eastern India. Besides being a freedom fighter, his ideas of customary rights to territories, control of dispossession and utilisation of land and natural resources of tribal communities seems to be useful and in many instances more relevant than the United Nations MDGs, Convention of Biological Diversities and state parties empowered by dominant jurisprudence of states.

The Munda rebellion or ‘Ulgulan’ (1895-1900) under the leadership of Birsa in the Chotanagpur region of Jharkhand was significant in three ways: the way it forced colonial government to introduce laws to regulate taking away of land of tribals by dikus (outsiders); the way it proved that tribals had the capacity to protest against injustice and to preserve customary laws through indigenous techniques; and the way it guided future policymakers to recognise Birsa’s idea of “historical injustice” in shaping the present day Panchayat Extension to Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act, Forest Rights Act (FRA) and several environmental movements of the twentieth century.

Birsa’s revolt had twofold objectives; first to protest against planned destruction of forest-based tribal society by the British and to drive out ‘dikus’ — dacoits or outsider non-tribals who made the tribal people dependent on them. The British laws stripped tribals of their natural rights. They tried to introduce zamindari/jagirdari or thekedari (private property) tenancy system in place of traditional khuntkatti system (joint land holding by tribal lineages) of cultivation, to alienate the tribal peasantry. In a similar way, the ‘dikus’ caused indebtedness, slave like existence and beth-begari (forced labour) among tribals. Birsa waged a guerrilla war against a diku-backed British government in the 1890s. The bow and arrow, though, was no match for British firepower and Birsa was caught and martyred in Ranchi Jail June 9, 1900.

Though the movement was short-lived, its impact was powerful; it forced the state to take effective measures to solve problems of the adivasis of Chotanagpur belt. Among such measures, an initial one was the abolition of beth-begari and introduction of Chotanagpur Tenancy (CNT) Act in 1908. The Act was aimed at providing a degree of protection to the tribes of Chotanagpur by making khuntkatti tenures secure from encroachment by landlords; it fixed rents in perpetuity and made sale of these lands for any purpose other than arrears of rent illegal. The establishment of khuntkatti rights served as beacon for other rights existing today in the tribal areas of India.

Birsa’s rebellion and self-perception were assimilation of two powerful mindsets: messianism and revolutionary activism. He advised his followers to pursue their original, traditional tribal religious system, particularly against large-scale deforestation — by the outsiders for farming and the British for developing industries.

Marxists suggest Birsa’s rebellion was an agrarian revolt of tribal communities, as it has its roots in Indian Forest Act which deprived tribal groups of their land. Subaltern theorists suggest an indigenous political-theological movement, as it targeted toppling of power structures and attack on Christian missionaries.

Contrary to theoretical discourse, Birsa Munda proved that adivasis were historically never under the ‘external system’ and were not demanding justice for themselves from the biased and oppressive system; their right to decide for themselves and the desire for natural freedom must be recognised.

Birsa proved before the colonial government that the existing customs, such as those regarding forest occupancy rights and right to claim land, were better than their statutes. Because these have provisions of self governing strategies, even the least assertive individuals had a voice; it opposed the idea of private property and believed in community ownership and collective action. The British were forced to enact laws such as the CNT Act based of Birsa Munda’s idea of natural rights and justice.

The writer is assistant professor, Centre for Tribal and Customary Law, Central University of Jharkhand, Ranchi.