Akira Kawamoto

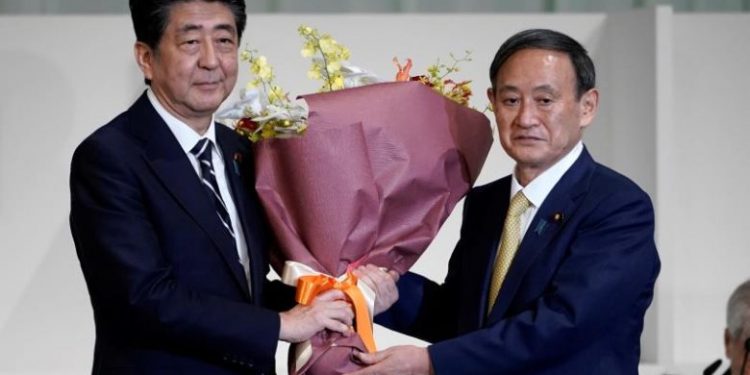

Yoshihide Suga has been selected as the new prime minister of Japan. He will replace Shinzo Abe, who announced his resignation last month for health reasons after almost eight years in office. Japanese and international observers are now asking whether the Abe government’s economic-policy course (dubbed ‘Abenomics’) will change significantly under Suga; and if so, how.

The answer will have important geopolitical implications. Japan, after all, is still struggling to overcome the negative shock from Covid-19, and its economic health is becoming ever more pivotal in view of the deepening confrontation between the United States and China. Many outside Japan might assume that Suga will change little, and he presented himself to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) as the ‘continuity’ candidate to replace Abe. That was, perhaps, the best card that he could have played, having served as cabinet secretary, the second most powerful position in Japan, for the entirety of Abe’s eight-year tenure.

On this view, Suga will remain safe by sticking closely to Abenomics. The massive quantitative easing undertaken since 2013 by Bank of Japan (BOJ) Governor Haruhiko Kuroda – an Abe appointee – will continue. Similarly, Suga will avoid vigorous and hasty fiscal tightening, even though the Abe government’s pandemic-response measures have further increased Japan’s net public debt, which, at around 150 per cent of the GDP, was already the highest among developed countries.

But if Japan is to sustain its global position, Suga must make a clear break from his predecessor and patron, and pursue a broad range of structural reforms. Indeed, productivity-enhancing labour-market and regulatory reforms are almost certainly the only way to increase Japan’s economic growth. Although Abe’s policies helped end Japan’s deflationary stagnation, the overall record of Abenomics is not very impressive. Between 2013 and 2019, annual GDP growth averaged just 1 per cent, and exceeded 2 per cent in only two of the eight years of Abe’s premiership. Moreover, BOJ data show that growth under Abenomics resulted mostly from increases in capital and labour inputs, rather than from productivity gains. Contrary to the conventional view that the Japanese economy faces strong headwinds owing to its aging population and shrinking workforce, the number of people in employment continued to grow throughout the Abe years, because more women joined the labour force. But with Japan’s female labour-force participation rate now higher than that of the US, this trend may not continue for much longer.

Stalled productivity growth strongly indicates that the Abe administration’s structural reforms (often called the ‘third arrow’ of Abenomics) fell far short of what Japan required. True, Japan’s rescue of the 12-country Trans-Pacific Partnership trade pact following the withdrawal of the US by President Trump, and its recent free-trade agreement with the EU, are substantial and praiseworthy achievements, particularly given the increase in protectionist sentiment that Trump has fostered. The Abe administration also made strong progress on corporate governance. But the aggregate impact of Abenomics was simply too small. Given his consistently high approval ratings and savvy economic advisers, why did Abe fail to pursue bolder structural reforms? One answer is he did not have to, because of lack of effective opposition parties offering alternatives.

Another answer is that Abe had a big, non-economic policy priority – revising Japan’s pacifist 1947 constitution – and always intended to spend his political capital on that issue. But he ultimately failed to achieve that goal, too, because there was never a moment when constitutional reform could command anywhere near majority support among the electorate.

Promoting wide-ranging structural reforms of the type that his predecessor largely avoided will require Suga to face down powerful lobbies and vested interests – many of them in his own ruling Liberal Democratic Party – and mobilise public opinion skillfully. But some of Suga’s remarks during his recent LDP leadership campaign offer hope that he may be a more daring and courageous prime minister than many expect. For example, Suga explicitly welcomed the idea of allowing new competitors to enter heavily regulated sectors such as mobile telecommunications and agriculture. He also announced his intention to establish a new agency tasked with overhauling the government’s digital infrastructure. Other clues come from Suga’s tenure as cabinet secretary, when he prodded Japan’s bureaucrats to change policies hitherto regarded as untouchable. Easing restrictions on visa issuance paved the way for a vast increase in the number of foreign tourists visiting Japan in recent years.

Nonetheless, much uncertainty lies ahead, and Suga will face two immediate hurdles. First, he must visibly establish his own leadership style. Whereas many of Suga’s predecessors as prime minister – including Abe and Taro Aso – hailed from well-known political (even aristocratic) families, Suga comes from a solid middle-class background. Although Suga proved himself an extremely capable manager as Abe’s cabinet secretary, his new role will require him not only to administer, but also to lead. Rather than pulling strings behind the scenes with elite bureaucrats, Suga must inspire the country. His first test will be to lead the government’s response to the pandemic, because the Abe administration’s confusing signals as to whether more restrictions are preferable to more economic activity – or, indeed, the reverse – have often bewildered the Japanese public. Suga’s second hurdle will be to consolidate power within his party. He was elected LDP leader with the support of the party’s major factions, but does not belong to any of them. Once he has appointed his cabinet, the LDP’s internal rivalries and fissures will likely re-emerge.

Suga’s best strategy might well be to go to the voters soon. Winning a general election, rather than just an internal party contest, would give him the popular mandate he needs to chart a bolder economic-policy course.

The writer is a former deputy director general in Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry. @Project Syndicate.