Few minutes into Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Soufflé (Breathless, 1960), after fleeing the city in a stolen car, on an empty road, surrounded by open fields, the protagonist Michel, absorbing the beauty around him, says, “Nothing like the countryside!”

In the opening scenes of Adieu Godard, director Amartya Bhattacharya takes us away from the city, away from the tall towers and the noisy traffic, to an ordinary Odisha village, to the countryside.

There he weaves a story of an old man, his daughter, and their individual quests for agency in life. The father, Anand, buys from a local store cassettes of pornographic films which he watches at home, in the company of a few friends, while subjecting his innocent wife and daughter to the sound of moans and grunts. And he is absolutely unapologetic about this obsession of his, despite people of the village calling him an “old pervert.” The daughter, Shilpa, school-going and ambitious, dreams of seeing the world, and getting some control over her future, her love-life and her life story.

Anand’s life takes a turn when the DVD dealer, who supplies him the cassettes, decides to change his business, and he gives Anand one last cassette, for free. Upon playing the DVD, he and his friends find that the film, which is in French, doesn’t contain any explicit sex scenes. While this frustrates the others, Anand is intrigued to see a film that goes against the wave of mainstream Indian cinema, a film in which characters don’t break into a fight or a dance sequence.

After this experience Anand is convinced that exposure to such films will provoke thinking in the villagers, making them more critical and self-reflective. With that in mind, he takes up the challenge of public-screening a few films of Godard. But from here on what follows is a story of a man whose conviction and obsession lead him to tragedy and madness.

As a storyteller, Bhattacharya seems equally interested in how people differ in their responses to art, why a film that pushes Anand on a journey of enlightenment, drives the youth of the village to frustration, anger, and violence.

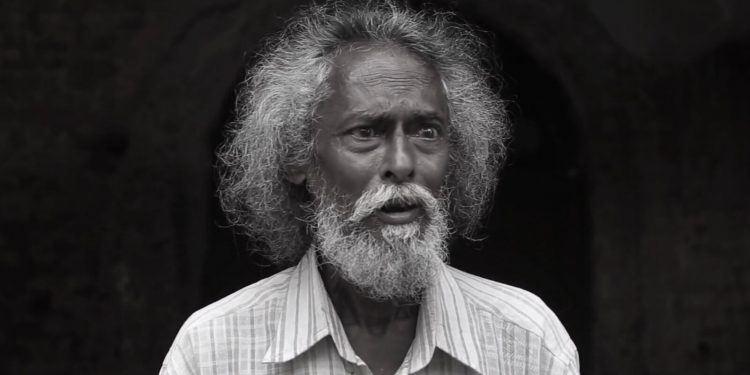

The cinematography, also done by Bhattacharya, complements the narrative. When Godard’s film is screened for the village people, we see close-ups of their faces, their wrinkles set in awe and confusion. Part of the film is in B&W, seemingly to imply a time that has passed. Another part, in colour, suggests the present day. And other parts, desaturated, mark the episodes in between, or the territory that lies between fact and fiction.

Also Read – World premiere of Odia film ‘adieu Godard’ to be held at Moscow International Film Festival

The editing is neat and crisp, the background is full of sounds that define the village, and the music by Kisaloy Roy is minimal yet fitting (shout out to the “Asantu” rap).

Notwithstanding the euphoria surrounding its screening at various festivals, Adieu Godard has its share of flaws. If not pointed out, it will certainly be a disservice to the filmmakers and the film community.

The lines delivered by some of the characters, Joe and Shilpa in particular, sound made-up, unnatural, inauthentic, to my Odia ears. Similarly, the character of Pablo seems depthless and under-developed, the entire episode with him feels like an afterthought. The ending too looks ambiguous. Though it’s fun to have an ending that leaves the viewer with some questions, unlike films such as The Lost Daughter (Maggie Gyllenhaal, 2021), which also featured an ambiguous ending, here the ambiguity feels a bit forced and imposed.

On the acting front, Choudhury Bikash Das as Anand is phenomenal as always. On the big screen, his face turns into a canvas on which you see colours of emotions appear, spread, merge and disappear in one another. As his co-conspirators Shankar Basu Mallik (Jaga) and Choudhury Jayaprakash Das (Harideb) are amusing and convincing. As Jatin, Swastik Choudhury, who is also a producer of the film, brings humour to the script and should get an award for performing a whole range of “hmms”.

Adieu Godard, despite its shortcomings, qualifies as a milestone on the course of Odia cinema and marks a new beginning. Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Soufflé (Breathless, 1960) was a product of the revolution in cinema known as the French New Wave, a movement that brought to films new methods of editing and storytelling. Similarly, Adieu Godard has introduced to the Odia film-industry, and to the audience, a new language of cinema. It has succeeded in getting Odia people who had stopped going to the theatre to watch Odia films all hyped up, again, for an Odia film. But will this Adieu Godard moment build momentum and become a movement?

That’s for time to tell.