Santosh K Patra

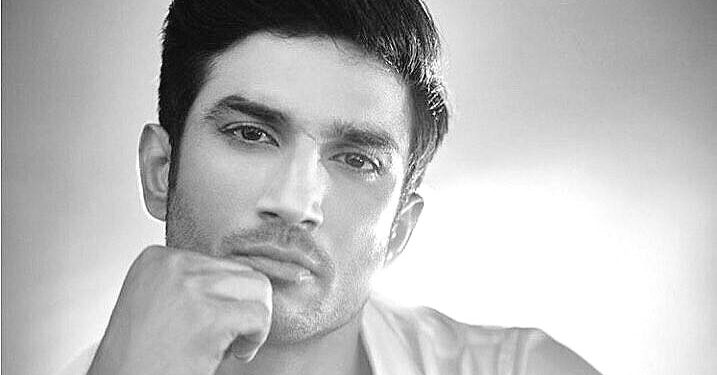

Earlier this month, popular actor without any B-Town blood Sushant Singh Rajput was found dead in his apartment. He was 34; an excellent student, an astrophysics enthusiast, a philosopher at core, a dance freak, social service-minded and philanthropist. He was just out of the conventional fulcrum in his acting career. The suspected suicide has upset his fans. As mystery continues to shroud this unfortunate incident, the reality of India’s imagination personified through the Hindi cinema is unfolding.

Popularly known as Bombay’s Hollywood, the B-Town as an industry is larger than life. From Dadasaheb Phalke’s silent cinema Raja Harishchandra (1913) to the highest Bollywood grosser till date Dangal, Bollywood has traversed myriads of paths, woven many dreams and ruined dreams too, to now stand as a `206-billion business. In this journey of more than 100 years, Bollywood has not only evolved in its scope, scale and size, but also created a visibly protected empire or power centres of a selected few in the lines of the laws of inheritance. The two major questions pertinent here are:

Firstly, why is the Indian film industry, particularly Bollywood, low in terms of its business than of its global counterparts, despite making the largest number of films? Secondly, are protected empires or power centres of Bollywood systematically destroying its growth to protect the idea of a guarded kingdom? SSR, an “outsider” with no blood/or general connection to Bollywood, has, with his death, pulled the G-string of Bollywood to fathom the outlined questions here.

While attempting to unfold the realities of the Bollywood, and in retrospect, one could perceive that the eventual process of cinematic craft that started with a passion for the profession has over the years bred insecurities among its self-proclaimed protagonists, pulling down the Bollywood’s growth story. Power of being larger than life, power of becoming the superior human, power of seeing everybody as the “others” and power of shielding the hereditary journey of Bollywood empires have led to a situation of black economy driving the industry for a long time now. This is the primary reason why Bollywood has always been criticised as one of the most-unorganised cinema industries in the world.

Until very recent, and now too, most of the movies are driven by either specific individuals or home-grown empires of Bollywood, disallowing the craft called cinema to evolve. This nexus of power has been age-old and history too suggests that there has been a huge influence and investment of underworld dons in the Bollywood and in its actors. There were many cases, as also proofs against film personalities in connection with their involvement in illegal activities. Even the politics within has successfully salvaged the larger-than-life images of Bollywood, fetching votes and securing seats in central representative bodies.

When we vote for cinema celebrities in elections, we as spectators are making these celebrities godly and powerful. Popular stars like Rajinikanth and Amitabh Bachchan have not only won a special place in the hearts of millions but have also their statues put up in temples. This culture of worship of humans has contributed immensely to mediocrity in Bollywood, where cinemas starring these godly celebrities usually become a blockbuster just on the mention of their names in the casting list. The worship culture has stood in the way of the industry achieving excellence and this has also allowed the power centres to breed within these set-ups.

So much so, today, though the opening of the Indian economy saw the Indian cinema being accorded Industry status, Bollywood primarily continues to be individual-driven and family-run business. It has worked as a major force for restricting the industry from opening up for “others” (read outsiders), both in terms of creativity and business-wise. Though companies like Fox Star, Disney, UTV (now part of the Disney Star Network), Viacom etc have ventured, the obsession of ‘we vs others’ still rules Bollywood.