Guru Prasad Mohanta

Although tuberculosis is treatable, the disease continues to be the single biggest cause of death worldwide. Each day, about 4,500 people die from TB, and close to 30,000 are affected by the disease. Sustained efforts have averted about 54 million deaths from 2000 to 2017. India has the highest proportion of TB patients, accounting for 27 per cent of the global burden. More than four lakh people died from TB in 2017. The country also has the highest number of Multi-Drug Resistant TB (MDR TB). As many as 1,35,000 cases were reported in 2017. The country aims to eliminate TB by 2025.

Ending TB globally by 2030 is a Sustainable Development Goal. The World Health Organisation, too, initiated an ‘End TB Strategy’ in 2014, which called for 90 per cent reduction in TB deaths and 80 per cent decrease in TB incidence by 2030. As part of the global commitment, the first-ever United Nations High Level Meeting on Tuberculosis last September resolved to end the disease as a global priority. World leaders have committed to initiate major steps towards building a TB-free world. India’s target is five years ahead of SDG. The world is looking at India’s performance to replicate it in other high TB burden countries.

The Karnataka government has taken a lead in announcing a reward of Rs 1,000 for the informer reporting a case of tuberculosis to public health authorities

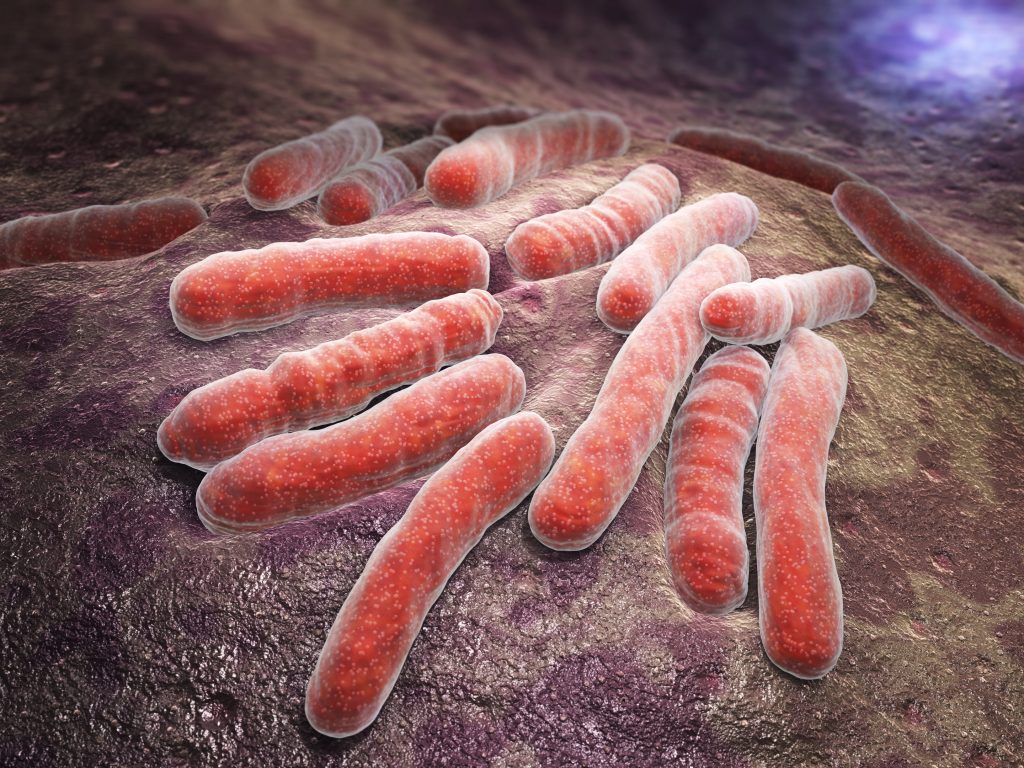

A recent ‘Lancet’ study suggests that untreated or poorly treated patients in the private sector are a major source of transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the organism that causes TB. The high incidence of transmission owes to delay in diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Improved diagnosis and treatment at private facilities is important to rapidly reduce TB transmission. In India, about 80 per cent of patients seek early treatment in the private sector.

Treatment in the private sector has long-lasting and catastrophic economic burden. The study has shown that individual patients in rural India had severe financial hardship even seven years after completing treatment. The Strategic Plan of TB control committed to large expansion of private providers’ engagement and calls for sixfold increase in private notification to 2 million patients a year by 2020. This equals to 75 per cent of the estimated incidence of TB. The government has not only made TB a notified disease but also made non-notification of the disease by the private sector punishable. The notification mandates that doctors treating tuberculosis patients, pathological laboratories and pharmacists dispensing medicines need to notify public health authorities about incidence of the disease. Penal provisions of jail term for not reporting TB cases can bring in unaccounted patients.

TB notification has, in fact, increased to 2.15 million in 2018, an increase of about 16 per cent from the previous year. Private sector notification has seen a 35 per cent increase. This is still just one-fourth of the desired level. The strategic plan is for a six-time increase in private notifications to two million patients per year by 2020.

One of the biggest challenges before TB control in India is tracking undiagnosed patients getting treated outside public health facilities. To redress this, the Indian strategy aims to find drug-sensitive TB and drug-resistant TB cases with emphasis on reaching TB patients seeking care from private providers and undiagnosed TB in high-risk populations.

Finding active TB cases though door-to-door visits by healthcare persons is already launched. This would help bring undiagnosed TB patients in vulnerable groups to mainstream public health system for diagnosis and treatment.

The Karnataka government has taken a lead in announcing a reward of Rs1,000 for the informer reporting a case of tuberculosis to public health authorities. The informer could be the patient himself or herself, family, neighbour, chemist or doctor.

A tuberculosis-free India is not a distant dream if the necessary commitment is there. The problem that a large proportion of TB patients remains undetected and do not receive appropriate treatment must be given priority attention. Identifying prospective new patients would not only reduce diagnostic delays but also initiate prompt treatment. This would largely prevent transmission and reduce incidence. An untreated patient can infect 10-15 persons a year.

The writer is professor of pharmacy, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu.