Dhanada K. Mishra

Mahatma Gandhi said almost seventy-five years ago – “Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s need, but not every man’s greed.” This was at a time when the world was not yet faced with the threat of sixth mass extinction. Gandhi was driven by the idea of Leo Tolstoy (The Kingdom of God is Within You) and John Ruskin (Unto This Last) who were deeply affected by the all-pervasive inequalities in human existence leading to untold miseries. They were inspired by spirituality in a deeply secular non-religious sense as was Gandhi.

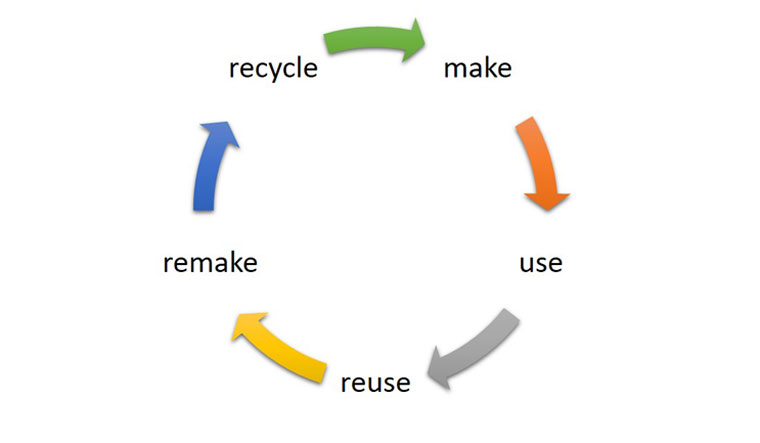

The Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman famously said – “The only corporate social responsibility a company has is to maximise its profits.” When such an approach drives much of the capitalist world’s business, the natural outcome is a greed-driven, consumerist society that results in fast depletion of natural resources, pollution, environmental degradation, and eventually the accumulated damage that has brought humanity to the verge of extinction. Such an economic model has been based on the so-called linear economy comprising of ‘Take, Make, Use, and Dispose’. In such a model, the true cost of goods and services is hidden due to a lack of accounting for the cost of pollution caused to the air, water, land, and sea as well as the remaining value of the product when discarded.

The idea of Circular Economy (CE) goes back to the nineteen sixties when the concept of the open economy, as opposed to the closed economy, was talked about by Kenneth Boulding. The use and throw model of the ‘Linear Economy’ was replaced by ‘Make, Use and Re-use’ model for the first time in the report by Walter Stahel and Genevieve Reday for European Commission in 1976. The best way to understand what CE is by examining a real-life case study. Take lighting for instance. It has always been known that a light bulb could be designed to last a lifetime but was never profitable to do so for obvious reasons. However, the current trend is to lease lighting as a service rather than lights as a product which is phrased by the lighting company Phillips as – ‘Circular Lighting’. Such an approach vastly reduces the huge amount of discarded lights from going to landfill. It incentivises the manufacturer to build the product to last as long as possible, design it for easy re-cycling and also take responsibility for the entire life cycle of the product. Apple is another good example. The company announced in 2017 that they will be making all new iPhones, iMacs, and other products from 100 per cent recycled materials. The company has been known for collecting back all its products at the time of an upgrade.

Modern lifestyle dependent on the linear or open industrial processes, uses finite natural resources to create products with a limited service life, that finally end up in landfills or in incinerators. On the other hand, CE is inspired by living systems like organisms that process nutrients that can eventually be fed back into the production cycle. Bio-mimicry, ‘cradle to cradle’ instead of ‘cradle to grave’, closed-loop, or regenerative are some of the other terms usually associated with it. The World Economic Forum, World Resources Institute, Philips, Ellen MacArthur Foundation, United Nations Environment Programme, and 40 other partners launched the Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy (PACE) in the year 2018 to scale up circular economy innovations. Global corporations like IKEA, Coca-Cola, Alphabet Inc., and DSM (company), along with governments of Denmark, The Netherlands, Finland, Rwanda, UAE, China are members of PACE. The British Standards Institution (BSI) developed and published the first standard for CE – “BS 8001:2017 Framework for implementing the principles of the circular economy in organisations” in 2016. A report by McKinsey titled “Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition” has identified the potential for significant benefits across the EU including net materials cost savings worth up to $630 billion annually only in the manufacturing sector. Most importantly, CE can contribute to meeting the emission reduction goals of COP 21 Paris Agreement. Since, greenhouse gas reduction commitments made by signatory countries, are not sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 degree C, it is estimated that half of the additional emissions reductions of 15 billion tonnes CO2 per year needed can be delivered by CE.

While CE can serve as a great model for a progressive economic and business framework, the world needs a broader approach that integrates complex socio-political ideologies that often drives the preference of economic models. In recent times, it has become increasingly clear that a free market-driven open-ended growth model is unsustainable and is the primary driver of global heating leading to the ecological breakdown and climate crisis. In 2012, Kate Raworth, a senior research associate at Oxford University, introduced the idea of a Doughnut economy in order to make human welfare the basis of economic policy rather than the all-pervading pursuit of growth in GDP. Economic welfare was defined as per the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that provide for a set of minimum living standards by the United Nations that should be treated as a matter of right for every human being. She extended the basic circular flow of money and goods model of economics by adding the nine planetary boundaries on the outside and social boundary consisting of SDGs on the inside – thus forming the doughnut. In this model, the economic progress was to be measured in terms of the balance between human wellbeing and protection of life support systems provided by the planet, thus mitigating global warming, ecological break-down, and climate change. Since its introduction, this post-growth economic thinking has attracted the attention of a range of actors ranging from the UN General Assembly to the Occupy London movement. As many communities, cities, states, and countries start re-examining prevalent strategies and economic policies in light of the current pandemic, the doughnut model is being explored as an alternative and even adopted by cities like Amsterdam for its future.

Gandhi was a lifelong proponent of ‘Gram Swaraj’ or the ‘village republic’ which he discussed in his seminal book ‘Hind Swaraj’. In it, he had promoted the idea of self-reliance and living within one’s means and in harmony with nature. The ideas of CE and Doughnut model seem to be imbued in that spirit of each person taking only as much as required and organising society into self-sufficient communities with a deep concern for our planet.

The author is a visiting research scholar, Hong Kong University of Science & Technology.