In his over three-decade-long career as a Bollywood director-producer, he had just half-a-dozen pictures to his credit, out of which two remained incomplete. Yet, “Mughal-e-Azam”, finally completed and released in 1960 after what seemed like an interminable gestation period, is enough to cement K. Asif’s reputation.

“Mughal-e-Azam” had everything a successful film could need — a riveting story, crisp dialogues, lavish production values, two accomplished actors playing the principal protagonists with their usual bombast and restraint, respectively. Then, most importantly, a host of melodious songs, including one by a living legend of the Indian classical music world.

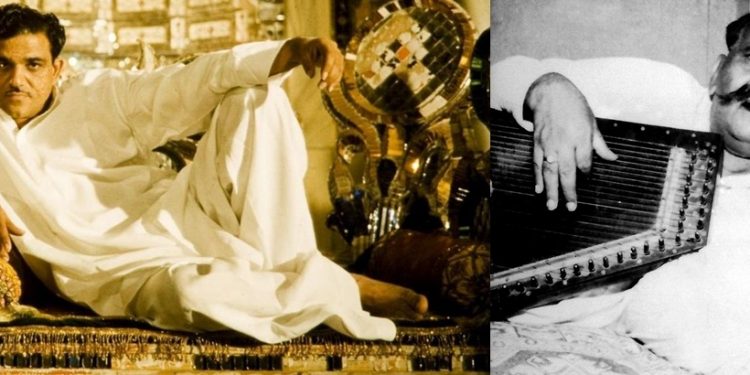

And the last one was a major coup by Asif, born Asif Kamal on this day in 1922, making it his 100th birth anniversary. We have music maestro Naushad to tell, in his inimitable way, how Asif convinced Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan to lend his voice for the film.

Classical singers such as Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, Pandit D.V. Paluskar and Ustad Amir Khan had been roped into films, but Khansahab had stayed away.

As Naushad has recounted in several interviews, Asif asked him one day who should render the voice of Tansen, and he replied that it could be only the “Tansen of the time”, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahab, but added that he did not sing for films. Asif peremptorily brushed this aside, saying, “You arrange a meeting and I will do the rest.”

Naushad compiled and they called on the Ustad the next day. After the usual pleasantries, Khansahab asked them how they had come and Naushad said that a landmark film, “that had never been made before or would be made again”, was in the process and they would like him to sing in it.

Bade Ghulam Ali Khan was dismissive, saying if it was a concert or something like that, he would be glad to participate in it but films were something he was not keen on. This is where Asif interjected — Naushad noted in his rendition that he had a habit of smoking with the cigarette between the second and third fingers, not the first and second as common, and flicking off the ash with a snap of his fingers.

“Khansahab, you will sing for us,” he said, taking a drag and snapping his fingers, leaving the Ustad taken aback with his brashness.

As Naushad relates, Khansahab reiterated politely that he was not keen on their offer. Still, retaining his courtly manners, he asked Naushad who this individual was and was not moved upon knowing he was a leading director and producer.

As Naushad went on to recount, Asif again dragged on his cigarette, snapped his fingers and repeated: “Khansahab, you will sing for us, name your price.”

At this, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan drew Naushad outside for a private conclave. He began: “Who is this man anyway? He keeps on insisting, despite my polite no. I will say something that will make him run away.”

Naushad recalled that he remonstrated, saying it would be his own loss. When Khansahab asked how, Naushad said that he would lose the opportunity of working with such a Titanic personality. Then, Naushad asked what the Ustad would say, Khansahab replied that he would quote such a figure that Asif would not go ahead. Naushad told him that this was his prerogative.

They went back and Khansahab told Asif his terms — one song and he would take Rs 25,000. Naushad here notes that at that time, the top playback singers just took Rs 500 to Rs 1,000 a song.

Asif’s response was masterly. “Only Rs 25,000 (drag on cigarette and snapping of fingers)? Ustad, you are priceless. Here is your Rs 10,000 advance.”

The Ustad was taken aback at this ready acquiescence to his terms and told Naushad in an undertone, “He is a very considerate man.”

That was not the end of the story. On the recording day, Asif drew Naushad aside and told him to instruct the maestro to sing in a low and soft tone, given the scene was set late in the night. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan said he could sing only after he saw the scene. So, they cancelled the recording, edited the filmed scene that day, made a loop of it, and arranged a new session the next day.

Avidly watching the scene where Prince Salim (Dilip Kumar) caresses Anarkali’s (Madhubala) cheek with a feather, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sang along and the result — “Prem Jogan Banke” — is pure magic, in all senses of the word.

Tragically for Asif, nothing he did later could match the scope of his magnum opus.

Having debuted with the box-office success, “Phool” (1945), he spent the rest of his life planning and shooting “Mughal-e-Azam”. After it, he planned a remake of the Laila-Majnun story in “Love and God”, but this seemed to be jinxed.

Shooting was put on hold when his choice for the male lead — Guru Dutt — died in 1964. He then recast Sanjeev Kumar as the lead, but Asif’s own death in 1971 led again to the shelving of the project. It was finally released in an abbreviated, incomplete form in 1986 after Sanjeev Kumar’s own death.

IANS