Ghasiram Panda

The National Education Policy of 1986, which called for special emphasis on removing disparities and equalising educational opportunities, was a milestone in India’s education—policy-making.

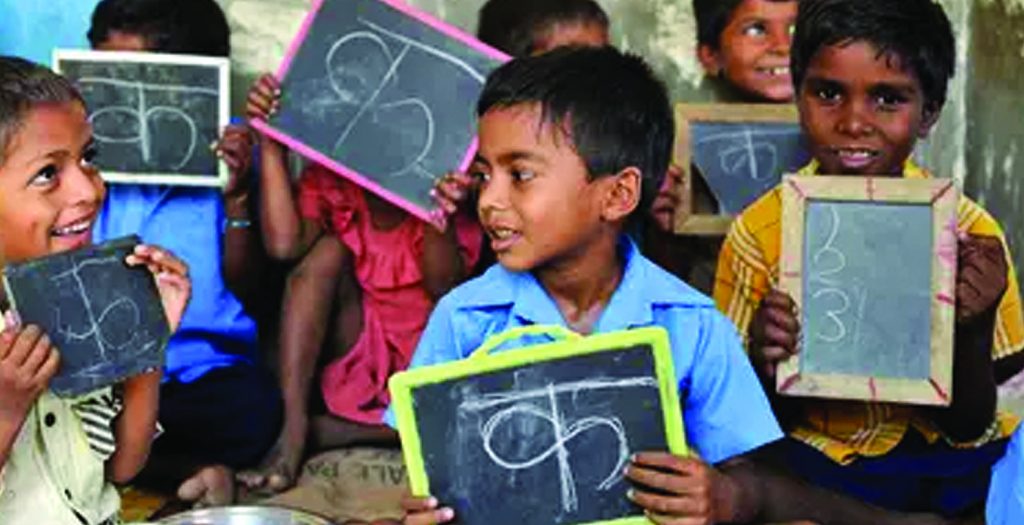

The Rights of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, popularly known as RTE Act, enacted in 2009, took it to another level by recognising education as a fundamental right. As RTE created a paradigm shift in elementary education in India, a change in policy was also expected.

Of late, the central government has proposed a new educational policy, which is a welcome step. The age of children has been defined differently in different laws. The RTE Act defines those under 14 as children. But in the proposed national education policy, the scope of free and compulsory education has been expanded to the age of 18.

The new policy proposes relaxation of RTE for privately managed schools. This will be instrumental in ruining government-run schools and a cause for social inequality

This proposal may have a positive impact on girls dropping out of school after the age of 14. Young girls drop out of school owing to the lack of opportunities. Currently free and compulsory education is up to 14, and schemes for girls such as the Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya end with Class VIII. As a result, socially backward and/or economically disadvantaged children are unable to continue studies further. Hence many girl children are forced to stay at home. It often leads to early marriage.

Child brides under the age of 14 can be rescued and re-enrolled in schools for education, whereas girls in the age group 14 to 18 don’t have such scope as they fall beyond purview of free and compulsory education. In many cases, it is also difficult to enrol them in vocational or skill development training, as they are minors.

In such a context, if the age limit is raised to 18, as proposed by the new National Education Policy, it will surely help to address these issues. This will also be great support in preventing child marriages.

However, only expanding the age limit will not work. Owing to the lack of infrastructure, and adequate number of (quality) teachers, schools in the neighbourhood, many boys and girls find it difficult to access education. The draft policy proposes to engage volunteers in delivering teaching-learning process. A volunteer dependent system will not ensure consistency and sustainability. Facilitating classroom learning requires skills. Hence, no one without such specific training should be allowed. Volunteers may be useful in mobilising communities and children, but they are not suited for classroom transaction.

We are still in multi-grade and multi-class teaching-learning arrangement. This can be a stop-gap arrangement and should not be a permanent setup. Time has come to appoint teachers according to class and subject. Investment in improving education should not be considered a burden.

The draft policy proposes creating ‘school complexes’ by merging schools. The government has already taken measures to close down schools where enrolment of children is poor. While this is debatable and many are opposing the closure, the proposed policy seems to be in favour of the concept of school complex. The Orissa Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Rules, 2010, has defined schools in the ‘neighbourhood’ as 1 km for primary and 3 km for upper primary. The proposal for school complex may defeat this purpose.

Unless the school is available at an accessible distance, the expansion of age limit up to 18 will also not be feasible.

Tribal children lack interest in studies owing to language gap that results in dropouts. The draft policy proposes community engagement to bridge gaps in language teaching. Recruitment of teachers at the local level should be given preference to resolve this issue. This will help strengthen community ownership.

The new policy proposes relaxation of RTE for privately managed schools. This will be instrumental in ruining government-run schools and a cause for social inequality. The vision of equal education for all can be realised only when elementary education is managed by the government itself. The new education policy offers scope for this.

The writer works as programme manager, ActionAid India.