Since Karl Marx coined the phrase, it has become an axiomatic truth for Communists of all denominations to consider religion as ‘the opium of the masses.’ The logical corollary to it for Communist countries is to remove all vestiges of religions and subject people following religious faiths to different forms of repression. This has been the case in China too which is now at the centre of an international conflict over its handling of religious groups in the country, including the Uyghur Muslims, Tibetan Buddhists and Catholic Christians in Hong Kong. The tension between China on the one hand and the USA and Europe on the other has got exacerbated by the USA’s recent decision to ban entry of products from China made with the labour of the Uyghurs settled in its Xinjiang province. In response, China has banned internet discussions of religions, rituals such as burning incense and followed it up with an unprecedented move to directly engage with the Christians of Hong Kong. The new measures have clearly spelt out the dos and don’ts in this regard. They stipulate that except for licensed religious groups, religious schools, temples and churches, no organisation or individual may preach on the internet, conduct religious education and training and publish or repost preachers’ comments. Organising and conducting religious activities and live broadcasting or recording of religious ceremonies such as worshipping the Buddha, burning incense, chanting, mass and baptism stand banned. Further, no organisation or individual is permitted to raise funds in the name of any religion on the internet.

The new rules, titled Measures for the Administration of Internet Religious Information Services, state that anyone applying for a licence to disseminate religious content online must be an entity or individual based in China and recognised by Chinese laws, and its main representative should be a Chinese national. State security authorities will manage domestic organisations and individuals and prevent them from ‘conspiring’ with foreign bodies to use religion to conduct activities that pose a threat to national security on the internet.

Under the rules, applications must be made to the religious affairs department of the local government for a licence that will be valid for three years. Content prohibited under the rules include those which use religion to “incite subversion of state power, oppose the Communist Party’s leadership, undermine national unity and social stability and promote extremism, terrorism or national separatism.”

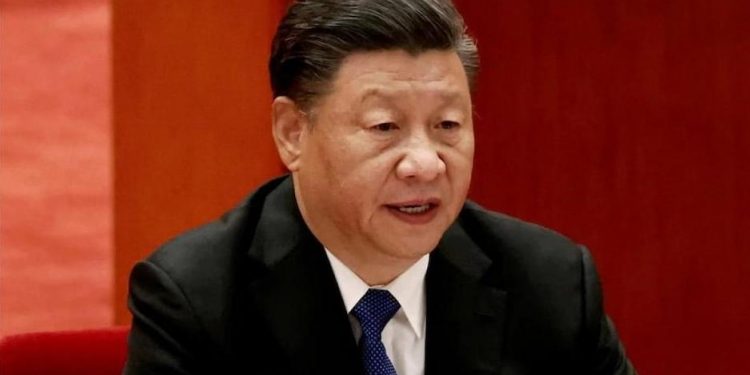

Realising the international build-up against the perceived persecution of religious groups, China’s President Xi Jinping early December adopted a persuasive tone to present his views on the state’s religious policies that is now known as ‘sinicisation’ which is religion with Chinese characteristics. His detractors, however, call it ‘Xification’ of religion, meaning Xi’s methods of curbing religious freedom. What is unprecedented is the move by Chinese bishops and religious leaders to brief senior Hong Kong Catholic clergymen on President Xi Jinping’s vision of religion. This is being construed as Beijing’s most assertive move yet to influence Hong Kong’s diocese, which is answerable to the Vatican and has some high-ranking leaders known for their credentials for defending democracy and human rights in the semi-autonomous territory. So long, mainland China contented itself by interacting with Catholic leaders of Hong Kong unofficially. But, it is the first time the two sides have met formally.

The outcome of the meeting is deliberately kept under wraps. Interestingly, as reports suggest, mainland speakers were careful not to mention Xi’s name at the meeting or issue any instructions or orders. They craftily explained that Xi’s policy of ‘sinicisation’ reinforces Vatican policies of ‘inculturation’, which means adapting Christianity in traditional, non-Christian cultures. The diocese has doubts about the wisdom of the Vatican’s conciliatory attitude to Beijing. The thrust of China’s arguments is that the policy of religion with Chinese characteristics means closer ties between religious groups and the party and state. It includes tying religions more closely to Chinese culture, patriotism and goals of the ruling Communist Party and state to achieve Xi’s ‘Chinese dream.’

This is a clever ploy to impose China’s authority on religious bodies without trying to appear too dogmatic. The political agenda behind it is for all to see and no one seems to be taken in by such pronouncements. The Hong Kong side also reciprocated by not adopting a confrontationist posturing. The meeting was held just weeks before the ordination this month of the new Hong Kong Bishop Stephen Chow who is a moderate Vatican appointee. Two earlier attempts to fill the post had failed due to pressure and opposition by Beijing. While some of Hong Kong’s government and commercial elites are Catholic and pro-Beijing, including the city’s leader Carrie Lam, other Catholics have long been active in the pro-democracy and anti-government movements.

The Hong Kong engagement is a desperate attempt by Xi to balance the relationship between religion and politics. An official white paper released in 2019 said China has about 200 million believers – majority were Buddhists in Tibet. Others included 20 million Muslims, 38 million Protestant Christians and 6 million Catholic Christians. There are 140,000 places of worship in China.

Xi, widely expected to remain in power for life, has been trying to reorient religions so that they can function under the guidance of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and he can continue to rule without too much international interference with his religious policies. Cajoling and cudgelling through internet ban appear to be his tools to push his religious policy.

These moves of Xi cannot be termed as purely Communist reactions towards religious movements. These are his personal requirements to rule over China for an unspecified time. The desire to use religion or to suppress it stem from a similar need. That need is the naked desire to remain in power.