Melvin Durai

I used to think that the only people who believed in conspiracy theories were the type of people you might find at a bank having an intense argument with the ATM. “You rascal! I’ve been watching you give notes to people, and I’ve been thinking, what’s he up to? Then I saw the word ‘reserve’ on one of those notes. What are you trying to reserve? Seats for your children in medical college?”

In other words, I thought the people who believed in conspiracy theories were a little unstable, to put it mildly. Who would believe, for example, that NASA faked the moon landing, that British intelligence agents were responsible for Princess Diana’s death, or that Mother Teresa was an undercover agent for America?

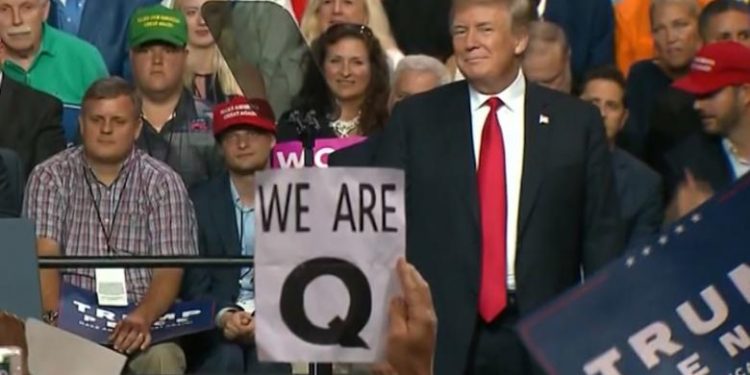

But in recent years, thanks partly to social media, there seems to be no shortage of conspiracy theories or people who believe them. If you follow the mainstream media, you may know that Joe Biden won the recent US presidential election convincingly, but you don’t have to look far to find theories claiming a stolen election. Among the theories: ballots for President Donald Trump were burned in large numbers, voting machines were programmed to undercount Trump votes, and thousands of mail-in votes for Biden came from people who are no longer alive.

It’s quite possible that a few voters died after mailing their votes, especially with COVID-19 being so rampant. But it’s less likely that people filled out ballots for their dead relatives. Americans are not that crazy. They might cast votes for their dogs, but not their dead relatives.

The COVID-19 pandemic has itself spawned dozens of conspiracy theories. One theory is that the virus was deliberately created in a lab in China. But if you ask conspiracy theorists in the Arab world, it was actually Israeli scientists who were working in the Chinese lab. And if you ask conspiracy theorists in India, you might find that the Chinese lab received 100 per cent of its funding from Pakistan.

Another theory is that the pandemic is a population-control scheme created by Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates. Anybody who believes this theory must also believe that newspaper reporters are wealthy from all the bribes Gates has given them to write positive articles about the Gates Foundation. Did the foundation really spend billions of dollars to help fight hunger and disease around the world? Perhaps the money went directly to a virus-creating lab (along with the millions from Pakistan).

That such theories exist isn’t surprising, considering all the motives people have for blaming one group or another. But what’s truly shocking and scary to me is the number of people willing to believe these theories. It’s not just oddballs living on the fringes of civilization; it’s our neighbours, perhaps even our friends. One study in 2014 found that at least 50 per cent of Americans believe in at least one conspiracy theory (hopefully not the one about Mother Teresa).

Because so many people believe in conspiracy theories, it’s hard to create a psychological profile of them, says Dr. Viren Swami, a professor of social psychology at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge, England.

We can’t label all of them ‘nutcases,’ especially not to their faces. A few of them certainly are, but the rest may be quite normal.

Swami told the Daily Express that people who rely on “more intuitive or emotional thinking” are more inclined to believe conspiracy theories, as are “people who feel powerless, people who feel under threat, people who feel they have no control of what’s happening around them.”

I can understand why a Trump supporter who feels powerless might want to believe that the election was stolen. But believing that Bill Gates is responsible for the virus? That’s a sign that you might need a counseling session with Dr. Swami.