Santosh Kumar Dash

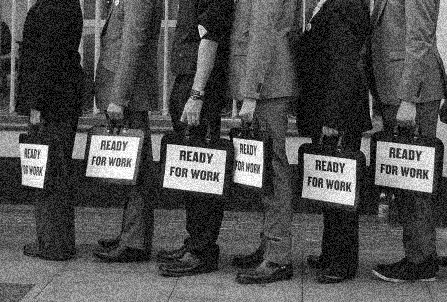

The accession of Trump to US presidency, the move towards exit of Britain from the European Union and the referendum in Italy have all given nightmares to economists chanting the mantra, “Free trade is good for everybody”. It is ironic that the sellers of free trade and globalisation are now batting for restrictions and protectionism. Beneath this call for mercantilism lies the rise in unemployment and inequality in most advanced countries. The majority of voters in industrialised countries now increasingly believe that job losses have risen as a result of free trade and globalisation. A careful reading of evidence, however, suggests otherwise. What exactly contributed to the loss of so many manufacturing jobs in the last one-and-a-half decade? Is it the much-blamed free trade and globalisation, or the less-blamed technological progress and innovation?

Initially, economists overlooked complaints about the rise in unemployment resulting from free trade. They opine that since trade increases efficiency of labour, surplus labour can be moved out of less efficient sectors and put where they are more efficient and competitive. They argued, and still do, that even if there are losers of trade, they could be compensated by the gainers.

But this has not happened in the real world, since it takes long for dislodged labour to find the next job elsewhere, and further, they may have to upgrade their skills to fit in the changing labour market. Truth is that while gains exceeded losses in almost all cases, the gains are not distributed across populations, at least not in a way that leaves everyone better off. And the result is before us.

While economists admit that trade caused manufacturing job losses, the role of technological progress in boosting unemployment has managed to escape scrutiny

In 2016, David Autor, David Dorn and Gordon Hanson in ‘The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade’ provided evidence of it for the first time. They argue that although consumers benefited from trade, it has had substantial adjustment costs and distributional consequences for local labour markets in which industries are exposed to foreign competition. They found that local labour markets adjust remarkably slow, and this has resulted in stagnant wages and low labour-force participation rates.

That globalisation causes unemployment is no more political rhetoric. Back in 2007, noted macroeconomist Alan S Blinder, who describes himself as a champion of free trade, voiced concerns about the consequences of offshoring American workers. He predicted that offshoring of service jobs from the US to India may pose major problems for tens of millions of American workers over the coming decades.

While economists admit that trade caused manufacturing job losses, the role of technological progress in boosting unemployment has managed to escape scrutiny. In recent years, major technological changes such as artificial intelligence, robotics and driverless vehicles have become major concerns for governments globally, as it results in job losses.

But, does technological change increase unemployment? Theoretical and empirical papers show that it has played its part. Theoretically, technological progress is always good for increasing work efficiency. However, it also puts low-skilled workers at risk as fewer people are required to produce the same output. Economists argue that gains from technological progress can be used to compensate workers who lose jobs, and to upskill and employ them in other industries. Unfortunately, the theory does not fit well in reality. Markets do not manage technological disruptions well, leading to long-periods of high unemployment and rising inequality. For example, in a paper titled ‘The Myth and the Reality of Manufacturing in America’ published 2017, Michael J Hicks and Srikant Devaraj have shown that technology, not trade, are major contributors to rising unemployment.

They found that 87.8 per cent of job losses in the manufacturing sector during 2000-2010 can be attributed to productivity growth, and the long-term changes to manufacturing employment are mostly linked to productivity of American factories, while trade contributed to 13.4 per cent of job losses.

Stiglitz, in his 2014 study, ‘Unemployment and Innovation’ argued: “The statement that such skill-biased innovation could be welfare-enhancing is usually taken to mean that the gains of the skilled workers are more than sufficient to compensate the losses of the unskilled workers. But while the skilled workers could compensate the unskilled workers, such compensation seldom occurs.” That technological change or innovation is always paired to improving needs to be critically examined. Stiglitz has in that paper theoretically shown that innovations not only fail to improve the welfare of all groups of society, but also to maximise output.

Similarly, in their 2014 study ‘Does Productivity Affect Unemployment? A Time-Frequency Analysis for the US’, Marco Gallegati, Mauro Gallegati, James B Ramsey, and Willi Semmler examined co-movements of productivity and unemployment over different time horizons using the US time series data and concluded that productivity creates unemployment in the short and medium terms, but employment in the long run.

Similarly, Carl Frey and Michael Osborne in a 2013 study, ‘The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation?’ examined the vulnerability of jobs to automation. Their estimates suggest that 47 per cent of total US employment is at risk.

Thus, technological progress, not international trade or globalisation, is a major contributor to the increase in loss of jobs in the short run. This is not difficult to see. Recall that at its core, free trade implies that countries should trade with each other the goods for which it has a comparative cost advantage with the other country. It must sell goods which it produces most efficiently and buy other goods from other countries in which it is least efficient. Thus, technological progress is the main driver of free trade and globalisation. By this extension, this contributes to rising unemployment. Hence, the government’s policies and efforts must be directed at saving workers, not jobs, by providing training programmes and wage subsidies.

The writer is an economist at the Center of Excellence in Fiscal Policy and Taxation, Xavier Institute Management, Bhubaneswar. Views are personal.