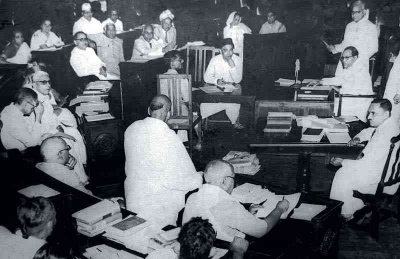

In the course of the nation setting out to firm up its foundation as a sovereign republic, the Constituent Assembly was elected to frame the Constitution of India.

Coming together for the first time December 9, 1946, the Assembly sat for 166 days to frame the Indian Constitution over the next two years and 11 months. The final session of the Constituent Assembly was held January 24, 1950.

It was on May 31, 1949, that the debates pertaining to the role of Governor took place in the Constituent Assembly.

Biswanath Das, the Prime Minister of Odisha Province in British India, who later became the Governor of Uttar Pradesh, anticipated the political clamour of present times — that a Governor nominated by the Centre is not acceptable to a state ruled by a different party.

Das had said: “The view that a person from his province should not be appointed a Governor, I strongly hold, and I tell you if that policy is adopted, we will simply bring the Governor into disrepute.”

B.R. Ambedkar, the Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, had insisted that the Governor need not be a merely ornamental entity.

He had clarified that although Governors will have no �functions’, they will certainly have �duties to perform’.

Ambedkar had pinpointed two duties: “One, that he has to retain the ministry in office. Because the ministry is to hold office during his pleasure, he has to see whether and when he should exercise his pleasure against the ministry.

“The second duty which the Governor has, and must have, is to advise the ministry, to warn the ministry, to suggest to the ministry an alternative and to ask for a reconsideration.”

K.T. Shah, known for his active role as a member of the Constituent Assembly, had held that “the Constitution should make it imperative upon the Governor to use its power in accordance with the Constitution and the law, that is to say, on the advice of his ministers as provided for in the subsequent clauses and in other parts of the Constitution.”

It was extensively debated whether the Governor should be appointed by the President or should be elected. In order to eliminate the possibility of creating a parallel state leadership, it was decided that the President will appoint the Governor.

Speaking on the now-contentious office, B.G. Kher, who went on to become the first ‘premier’ of Bombay State, had said: “A Governor can do a great deal of good if he is a good Governor and he can do a great deal of mischief if he is a bad Governor, in spite of the very little power given to him under the Constitution.”

In a situation of a clash, P.K. Sen, a member from Bihar, had said: “The question is whether by interfering, the Governor would be upholding the democratic idea or subverting it. It would really be a surrender of democracy. We have decided that the Governor should be a Constitutional head. He would be the person really to lubricate the machinery and to see to it that all the wheels are going well by reason not of his interference, but his friendly intervention.”

With respect to acting on the aid and advice of the Cabinet, Ambedkar had said that according to the principles of the new Constitution, “The Governor is required to follow the advice of his ministry in all matters. Therefore, the real issue before the House is not nomination or election, but what powers you propose to give to your Governor.”

There happen to be no explicit Constitutional provisions that specifically empower the Governors to seek information directly from the officials.

Article 167 is the only scope that says that the Governor can seek any information from the council of ministers and the Chief Ministers. However, this Article drew much opposition from the Constituent Assembly.

H.V. Kamath, a member of the Constituent Assembly, had put forth a strong argument against making it an obligation for the Chief Minister to submit all information called by the Governor.

He had said: “This is sort of putting the cart before the horse. I think with nominated Governors in the states, it should be left to the Chief Minister or the Premier of the state to decide which matter he would like to put before the Governor.”

The final word on the debate was Ambedkar’s, whose central argument was that the Governors will not have the power to overrule the decisions of the council of ministers.

It may thus be concluded that the Governor is by default empowered to delay or obstruct the decisions of the state government.

In letter and spirit, the Governor’s role is to assist the Chief Minister in the smooth functioning of the state.

It goes without saying that the Governor should not only not undermine the dignity of the Constitutional post, but must also abide by Constitutional morality while discharging his/her duties.

By Kavya Dubey

–IANS