Washington: An experimental vaccine is effective at preventing pneumonia in mice infected with the COVID-19 virus, according to a recent study. The experimental vaccine which is made from a mild virus genetically modified to carry a key gene from the COVID-19 virus is published in the journal ‘Cell Host and Microbe’. “Unlike many of the other vaccines under development, this one is made from a virus. This virus is capable of spreading in a limited fashion inside the human body. It means that this vaccine is likely to generate a strong immune response,” said study author Michael S Diamond from the Washington University.

“Our vaccine candidate is now being tested in additional animal models. The goal is to get it into clinical trials as soon as possible,” Diamond added.

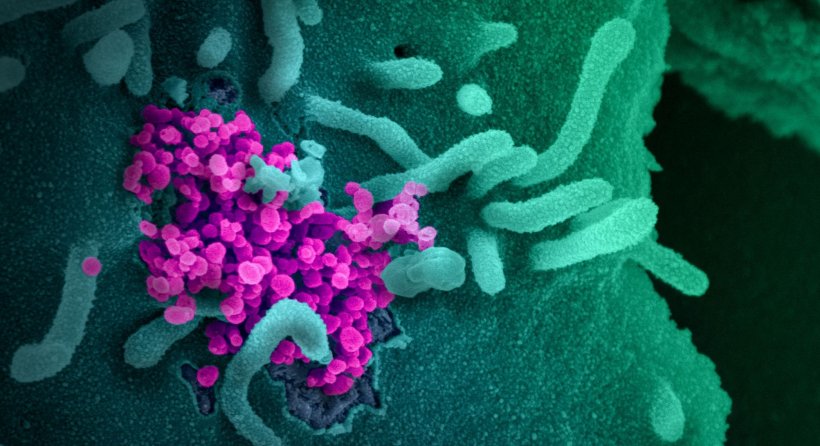

According to the study, the research team created the experimental vaccine by genetically modifying vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). It is a virus of livestock that causes only a mild, short-lived illness in people. They swapped out one gene from VSV for the gene for a spike from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. The hybrid virus is called VSV-SARS-CoV-2. Spike protein is thought to be one of the keys to immunity against COVID-19.

The COVID-19 virus uses spike to latch onto and infect human cells. The human body then defends itself by generating protective antibodies targetting spike. By adding the gene for spike to a fairly harmless virus, the researchers created a hybrid virus that, when given to people, ideally would elicit antibodies against spike that protect against later infection with the COVID-19 virus.

As part of this study, the researchers injected mice with VSV-SARS-CoV-2 or a lab strain of VSV for comparison. A sub-group was boosted with a second dose of the experimental vaccine four weeks after the initial injections. Three weeks after each injection, the researchers drew blood from the mice to test for antibodies capable of preventing SARS-CoV-2 from infecting cells. They found high levels of such neutralizing antibodies after one dose, and the levels increased 90-fold after a second dose.

Then, the researchers challenged the mice five weeks after their last dose by spraying the COVID-19 virus into their noses. The vaccine completely protected the mice from developing fever.

At four days post-infection, there was no infectious virus detectable in the lungs of mice that had been given either one or two doses of the vaccine. In contrast, mice that had received the placebo had high levels of virus in their lungs. In addition, the lungs of vaccinated mice showed fewer signs of inflammation and damage than those of mice that had received the placebo. “The experimental vaccine is still in the early stages of development,” the study authors noted.