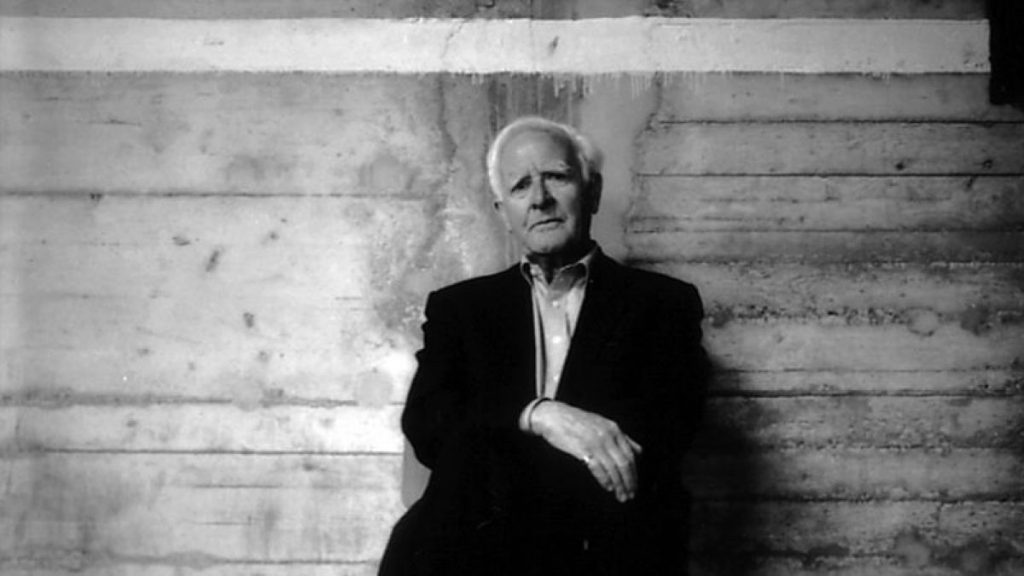

London: John le Carre, the spy-turned-novelist whose elegant and intricate narratives defined the Cold War espionage thriller and brought acclaim to a genre critics had once ignored, has died.

He was 89.

Le Carre’s literary agency, Curtis Brown, said Sunday he died in Cornwall, southwest England Saturday after a short illness. The agency said his death was not related to COVID-19. His family said he died of pneumonia In classics such as “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold,” “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” and “The Honourable Schoolboy,” Le Carre combined terse but lyrical prose with the kind of complexity expected in literary fiction. His books grappled with betrayal, moral compromise and the psychological toll of a secret life. In the quiet, watchful spymaster George Smiley, he created one of 20th-century fiction’s iconic characters — a decent man at the heart of a web of deceit.

“John le Carre has passed at the age of 89. This terrible year has claimed a literary giant and a humanitarian spirit,” tweeted novelist Stephen King. Margaret Atwood said: “Very sorry to hear this. His Smiley novels are key to understanding the mid-20th century.” For le Carre, the world of espionage was a “metaphor for the human condition.” “I’m not part of the literary bureaucracy if you like that categorizes everybody: Romantic, Thriller, Serious,” le Carre told The Associated Press in 2008. “I just go with what I want to write about and the characters. I don’t announce this to myself as a thriller or an entertainment.

“I think all that is pretty silly stuff. It’s easier for booksellers and critics, but I don’t buy that categorization. I mean, what’s ‘A Tale of Two Cities?’ — a thriller?” His other works included “Smiley’s People,” “The Russia House,” and, in 2017, the Smiley farewell, “A Legacy of Spies.” Many novels were adapted for film and television, notably the 1965 productions of “Smiley’s People’ and “Tinker Tailor” featuring Alec Guinness as Smiley.

Le Carre was drawn to espionage by an upbringing that was superficially conventional but secretly tumultuous.

Born David John Moore Cornwell in Poole, southwest England Oct. 19, 1931, he appeared to have a standard upper-middle-class education: the private Sherborne School, a year studying German literature at the University of Bern, compulsory military service in Austria — where he interrogated Eastern Bloc defectors — and a degree in modern languages at Oxford University. But his ostensibly standard upper-middle-class upbringing was an illusion. His father, Ronnie Cornwell, was a con man who was an associate of gangsters and spent time in jail for insurance fraud. His mother left the family when David was 5; he didn’t meet her again until he was 21.

It was a childhood of uncertainty and extremes: one minute limousines and champagne, the next eviction from the family’s latest accommodation. It bred insecurity, an acute awareness of the gap between surface and reality — and a familiarity with secrecy that would serve him well in his future profession.

“These were very early experiences, actually, of clandestine survival,” le Carre said in 1996. “The whole world was enemy territory.” After university, which was interrupted by his father’s bankruptcy, he taught at the prestigious boarding school Eton before joining the foreign service.

Officially a diplomat, he was in fact a “lowly” operative with the domestic intelligence service MI5 —he’d started as a student at Oxford — and then its overseas counterpart MI6, serving in Germany, on the Cold War front line, under the cover of second secretary at the British Embassy.

His first three novels were written while he was a spy, and his employers required him to publish under a pseudonym. He remained “le Carre” for his entire career. He said he chose the name — square in French — simply because he liked the vaguely mysterious, European sound of it.

“Call For the Dead” appeared in 1961 and “A Murder of Quality” in 1962. Then in 1963 came “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold,” a tale of an agent forced to carry out one last, risky operation in divided Berlin. It raised one of the author’s recurring themes: the blurring of moral lines that is part and parcel of espionage, and the difficulty of distinguishing good guys from bad. Le Carre said it was written at one of the darkest points of the Cold War, just after the building of the Berlin Wall, at a time when he and his colleagues feared nuclear war might be imminent.

“So I wrote a book in great heat which said ‘a plague on both your houses,’” le Carre told the BBC in 2000.

It was immediately hailed as a classic and allowed him to quit the intelligence service to become a full-time writer.

His depictions of life in the clubby, grubby, ethically tarnished world of “The Circus” — the books’ code-name for MI6 — were the antithesis of Ian Fleming’s suave action-hero James Bond, and won le Carre a critical respect that eluded Fleming.

AP