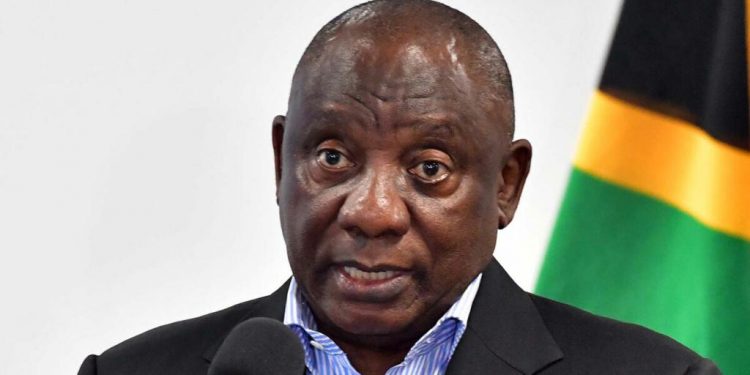

South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa hit bull’s eye when he lashed out at the rich countries for their failure to deliver the promised $100 billion in annual climate finance by 2020. He was speaking at French President Emmanuel Macron’s just concluded summit for a new global financing pact in Paris. It is true that a number of commitments made by developed countries towards climate change caused by their reckless carbon emissions have not been fulfilled. Ramaphosa was at his emphatic best when he said it is one thing for developed countries to promise to “make this available and that available” and another to translate the promise into action. Developing nations at the summit called for a “transformation” of the world’s financial system.

The two-day summit organised in Paris to expedite efforts to unlock trillions of dollars required to tackle climate change barely addressed the underlying problems preventing developing countries from investing in development alongside climate measures, especially with their crushing debt levels. Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, who co-hosted the summit alongside Macron, made the right noise when she called on the participants to chalk out a concrete path to transformation and not merely talk on reforming the global financial system. The summit made several announcements such as the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) declaration of reaching the target of making $100 billion in special drawing rights (SDRs), a reserve currency, available to climate-vulnerable countries. The World Bank also said developing nations hit by climate disasters would be able to suspend debt repayments. The International Energy Agency had made it clear in 2021 that developing new fossil fuel resources struck at the root of efforts to restrict global heating to below 1.5C, a dangerous threshold beyond which lie the most disastrous climate impacts. Yet, the oil and gas industry does not seem to care.

Last year alone, it pledged half a trillion dollars for new capital expenditure on future drilling and extraction. It made a profit of $4 trillion. No one denies the fact that without energy development, aspirations and basic present and future needs cannot be fulfilled. But, producing it from coal, oil and gas without developing sustainable energy sources is one of the major causes of the current climate emergency. The right strategy would be to consider climate, energy and development as interconnected. But, this has become increasingly more difficult to achieve in the post-COVID situation which hit poor nations hard with record levels of debt. The Russia-Ukraine war has compounded matters in the form of rise in interest rates and cost of living. Some developing countries are reportedly spending nearly five times of their health budgets on meeting debt obligations. The tardiness of the IMF in ensuring rich countries meet the target of setting up $100 billion climate fund for poor countries is in sharp contrast to the trillions of dollars mobilised in an instant to bail out finance houses during the financial meltdown of 2008. It is unacceptable that years are needed to raise funds to address the climate emergency. Efforts by leaders in North America and Europe of reshaping their energy systems by using key raw materials from poorer nations for producing clean energy should be based on give and take.

Poorer countries possessing the minerals should be helped to overcome the three structural deficiencies that block their development, namely a lack of food and energy sovereignty and low value-added manufacturing. This can be done in return for sharing their minerals. Unless a mechanism to this effect is created, the rush for clean energy would lead to corrupt deals as are done by fossil fuel companies which buy off politicians and recklessly damage the environment. The French initiative as exhibited in the summit is only one step in the long journey of reconfiguring decades-old institutions to finance efforts to keep the earth’s temperature below disaster levels.