Jayakrishna Sahu

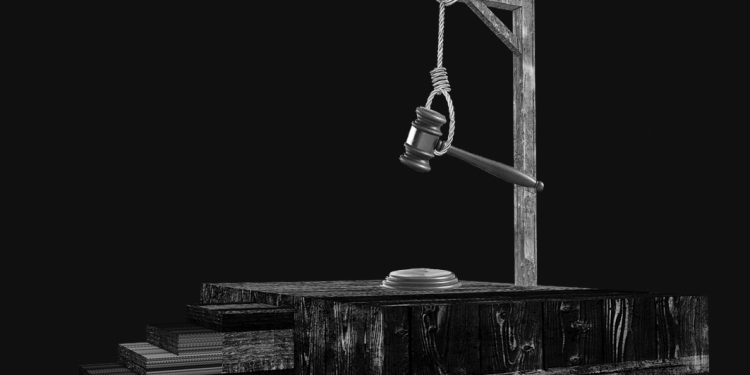

The unending legal high-drama surrounding the hanging of Nirbhaya rape-murder convicts has once again enlivened the debate on capital punishment. Whenever a crime is committed in the most barbaric and gruesome manner, the collective conscience of the society gets shaken. From people on the streets, to Parliamentarians, all demand the death sentence for such criminals whose survival places the society in danger. But human rights activists and even eminent jurists and liberal intellectuals demand abolition of capital punishment.

It cannot be denied that the dominant disposition globally has been in favour of abolishing the death penalty. Of the 193 member countries of the United Nations, 106 (55 per cent) have abolished capital punishment. Thirty-six (19 per cent) have retained it in law but do not implement it. Only 35 countries (18 per cent) keep it in law and execute it also, though many do it only in exceptional circumstances. India belongs to the last category of nations. We are thus part of a minority that is shrinking with time.

According to an Amnesty International report published in 2018, 2,531 convicts were awarded the death sentence in 54 countries; but only 690 were executed in 20 countries. This number was a decrease of about 31 per cent compared with previous year’s number. Most executions took place in communist and Islamist countries such as China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Vietnam and Iraq. Amnesty International says more than 1,000 secret executions are happening in China every year. In Islamic countries, death sentence is used as a weapon against religious minorities and political opponents. Saudi Arabia beheaded 37 Shias, including three juveniles, in April 2019.

But this does not mean only the failed, backward, communist, despotic or Islamic states retain the death penalty. Countries such as the US, Japan and South Korea have also retained capital punishment. The US executed 22 convicts in 2019 and 25 in 2018. Although 20 out of 50 US states have abolished the death-sentence, executions happen almost every year in America.

So the argument that death penalty has been abolished from the civilised world is surely not factual. In this context, India seems to have moved far ahead of the countries of the West. In India, during the last 72 years post-Independence, only 57 convicts have been hanged. Between 1991 and 2015, only 16 were hanged.

In India, capital punishment is provided in laws for offences of waging war against India, abetting mutiny in armed forces, false evidence which leads to death sentence of a person, murder, abetting suicide of a minor, abetting Sati, repeat acts of drug-trafficking, rape of girl-child under 12, rape which put the victim in a permanent vegetative-state and decoity with murder. In all the above offences there is an alternative of life-imprisonment. Only one provision in the IPC, Section 303, provided for solely the death sentence, that is, if a convict serving life imprisonment committed murder. Even this was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Mithu Singh vs State of Punjab (1983).

In the Bachhan Singh vs. State of Punjab, in 1980, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of the death sentence, but held that it could only be awarded in “the rarest of rare case”. In the Machhi Singh vs State of Punjab case (1983), the Supreme Court broadly defined and laid out guidelines on what constituted a rarest of rare case. The condemned prisoner in India also enjoys the right to file curative petition before the Supreme Court and mercy petition before the President.

Still, there is no dearth of arguments against capital punishment. Human right bodies argue that judicial killing of a human being cannot be encouraged as right to life is the most fundamental human right. The most vocal argument is that capital punishment has no deterrent effect on the criminals or probable-criminals, as statistics reveal.

There are equally strong arguments for retaining capital punishment. Though the majority of convicts can be reformed through punishment, there are habitual or hardened criminals who pose serious threat to the lives of people. In criminology and penology such behaviour is called “recidivism”. According to Pew Research Center, the rate of recidivism is more than 40 per cent in almost all developed western European countries and the US. National Crime Records Bureau data show that recidivism in India is 7-8 per cent and rising.

A few instances of recidivism are worth mentioning in this context. Giri Mandal of Jajpur had been convicted of the murder of his wife Chandi in 2003 and sentenced to life in 2004. He was released in 2016 on grounds of good behaviour after serving 12 years in prison. But just two years after release, in 2018, he committed another murder. The case of Nilu Swain, also from Jajpur, is similar. He had been arrested on charges of raping a woman in 2011 and was enlarged on bail in 2013. A week after his release on bail, he murdered the mother-in-law of the victim.

Even more interesting was the case of Javed of Jaipur, Rajasthan. His was a classic example of an incorrigible criminal. He was first convicted of raping and murdering a 11-year-old boy in 2004 and sentenced to life. But he was released after 12 years on grounds of good behaviour. After a few months, though, he was caught again for the theft of a tractor and imprisoned.

In 2017, he was again released on bail and this time he sexually abusing a minor girl and was again jailed. Yet again in February 2019, he was granted bail. Javed went on to rape two girls aged 5 and 7 years and then murder a person after snatching Rs 20,000 from him. When the police asked Javed why he was not giving up on crime, he replied: “I want to become a bigger criminal than my neighbour Rafiq.” He also said he enjoyed brutalising minor girls. On further interrogation he revealed that he had been eyeing several minor girls of his locality and was planning their execution.

Such cases make it clear that India cannot afford to abolish the death sentence. The Supreme Court justly upheld the constitutional validity of capital punishment in 1980. And India in 2007 was right in not signing the United Nations General Assembly resolution for moratorium on death sentence.

The writer is an advocate based in Bolangir.