New Delhi: The deadly Nipah virus kills nearly 75 per cent of the people it infects, but the circumstances under which the bat species, known as the Indian flying fox, transmits the virus to humans has remained a mystery.

Now, a six-year, multidisciplinary study has revealed how the Nipah virus, which claimed the lives of 17 people in Kerala in 2018, spreads among fruit bats — findings which can help predict when the pathogen may spillover to humans.

According to the research, published recently in the journal PNAS, the Nipah virus (NiV) could circulate among fruit bats, not just in places that have seen human outbreaks, but in any region where they exist.

“To prevent outbreaks in humans, we need to know when bats may transmit the virus, and this study provides a deep understanding of Nipah infection patterns in bats,” study lead author Jonathan Epstein from the EcoHealth Alliance in the US, told PTI.

While previous studies from Kerala, and parts of Bangladesh have shown that the Indian flying fox can transmit the virus, Epstein said there is a “theoretical possibility of human infections any time of the year, wherever these bats and humans make contact.”

However, it is critical to have these bats around since they are essential for pollinating seeds from fruit trees, said Epstein, who was part of the team that identified horseshoe bats as the animal host of the 2002-03 SARS pandemic virus.

“So it is not about getting rid of them, it is more important to understand the routes of virus transmission, and know when they contaminate our food and water,” he explained.

According to the disease ecologist, it is important to expand surveillance of the bats for the virus to other parts of India.

These bats are well-adapted to living with people, and are common across the Indian subcontinent, “extending all the way up to Nepal.”

“In villages we see hundreds to thousands of these bats roosted in hardwood trees. The size and density of these colonies matters,” Epstein said.

He cautioned that chasing the bats away will not solve the problem since it would only redistribute them to other trees, creating denser colonies.

The scientists said as long as 60 to 70 per cent of the bats in a population have protective antibodies against the virus, there’s unlikely to be an outbreak.

“What this study showed for the first time is that, over time, bats in the wild lose the antibodies which protect them from NiV reinfection,” Epstein said.

When a great enough proportion of bats are immune to the virus, there’s not much transmission, but when this fraction drops below a threshold the whole colony becomes susceptible, he said.

When that level drops, sometimes as low as 20 per cent, the population is like a pile of dry wood, and as soon as someone throws a match on — which is to say when NiV is introduced by an infected bat — you get a bonfire, an outbreak, Epstein explained.

The scientists said outbreaks among bats in Bangladesh seem to occur every two years, adding that it is important to understand this periodicity.

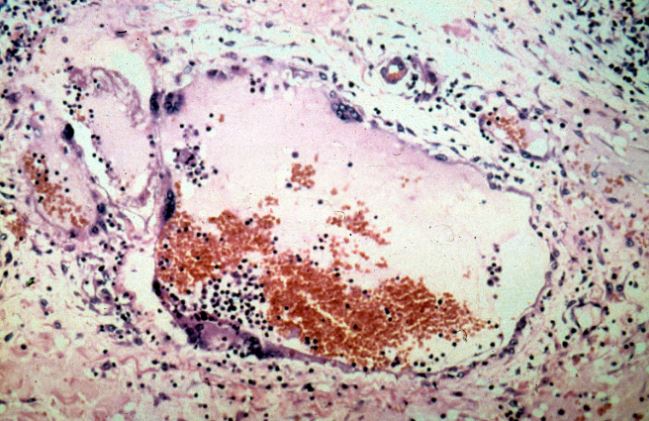

When there is an outbreak among bats, “the greatest number of them” will be shedding the virus in their feces, urine, and other body fluids, and create an opportunity for NiV to jump to people, Epstein said.

Studies have shown that the virus may spillover to humans via date-palm saps or fruits contaminated by infected bats.

“In an earlier outbreak in Malaysia, pigs amplified the virus. They got infected and generated a lot more virus than bats do. So people were getting infected by a large viral load,” Epstein said.

The researchers said people can be protected from exposure to the virus by “simply preventing date palms from contamination, or by not eating fruits with bat bite marks, and making sure such fruits are not fed to livestock.”

“Fortunately, the Government of India has been starting to pay attention since the Kerala outbreak, and is also conducting investigation in bats,” Epstein added.

This is vital to determine the spectrum of NiV strains circulating in India and South Asia, know if there are more-virulent forms of the virus, and to make generalisable predictions on when bats experience outbreaks, Epstein said.

He added that even if NiV outbreak among fruit bats in India may follow a similar cyclic pattern, the periodicity may be different.

Commenting on the study, virologist Upasana Ray, who was unrelated to the research team, said the findings highlight the importance of surveillance of animal pathogens to predict their odds of spilling over to humans.

“NiV is one of the many viruses transmitted by bats and is seen to hit the headlines every year, or every other year in countries including India,” Ray, a senior scientist at CSIR-IICB, Kolkata, told PTI.

She believes the identification of such viruses, and development of therapeutic strategies from early on might help decrease their effects on human lives.

“Nipah viruses continue to jump from bats to people and we can’t afford to wait for another pandemic to take actions,” Epstein said.

“Those actions don’t mean killing bats, but rather protecting our food from contamination with bat droppings,” he added.

PTI