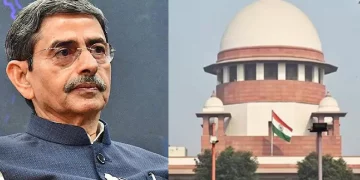

Pradeep Kumar Panda

Microfinance, or microcredit, refers collectively to the small loans provided to the economically weak to help them improve their livelihood. Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) have challenged the traditional banking system using concepts of joint liability and group lending. Over the years, microfinance programmes have become an important factor in reducing poverty and bringing social change.

In India, the movement took shape when National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) took up a pilot project, with some NGOs, of formally linking self-help groups (SHGs) with banks to meet credit requirements of poor households in rural India.

The high demand for microcredit propelled many types of organisations, including non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), into the sector. These were started with the genuine objective of helping the poor, but, over time, have drifted from their social objective and become linked to mainstream finance. Their focus has shifted from social goals to organisational goals such as higher profitability, repayment rates, and market share.

Empirical evidence suggests microfinance positively impacts household income, health, education of children and women’s empowerment; but some recent studies find that microfinance affects poor households negatively or not at all

It resulted in aggressive lending and undesirable recovery practices, which affected daily livelihood, social networks and the dignity and self-worth of poor households.

Repayment problems almost paralysed the sector in 2010–11. Default rates and suicides increased in villages, particularly in Andhra Pradesh. The sector, earlier characterised by high repayment records, suddenly started witnessing high loan defaults, and over-indebtedness among borrowers.

Over-indebtedness reflects not only the borrowers’ inability to repay loans; it also shows lack of professionalism of MFIs and their inability to evaluate creditworthiness of clients and to manage arrears and recovery practices. Over-indebtedness can perhaps not be eradicated, but it can be contained.

Historically, banks avoided lending to poor households owing to “information asymmetry”. Poor clients cannot provide any collateral owing to non-availability or non-existence of clear property rights.

MFIs emerged as a new paradigm in lending. To circumvent the typical problems faced in lending to the poor, MFIs introduced innovations such as group lending with joint liability, dynamic incentives, frequent repayment of instalments, and targeting women as clients. These features helped MFIs solve the problems of adverse selection, moral hazard, auditing, and enforcement; it reduced transaction costs associated with lending uncollateralised loans; and it improved financial viability. Access to future loans, regular repayment schedules and use of “social penalty function” also ensured that loans were repaid on time.

Empirical evidence suggests microfinance positively impacts household income, health, education of children and women’s empowerment; but some recent studies find that microfinance affects poor households negatively or not at all.

The rapid growth of MFIs and the entry of commercial lenders allows borrowers get credit from multiple lenders, weakening their repayment incentive and creating a warlike situation where MFIs vied for clients by offering larger loans, faster services and lower interest rates.

This resulted in higher debt among poor clients. When the economic condition stalled, they could not service loans. Concentrated markets, overstretched MFI systems and controls, and erosion in lending discipline led to high defaults in various countries.

The Indian microfinance sector was also on the verge of collapse because of high defaults in 2009–10. With rapid expansion in loan portfolio during the early 2000s, MFIs did not invest time in building relationships with clients or training staff, as in the initial years; rather, they engaged in predatory lending, unfair debt collection practices, charging very high interest rates, and mis-selling of microcredit products. The immediate result of the crisis was the rise in suicides and political backlash.

Existing studies confirm over-indebtedness in microfinance and that it hurts both poor clients and microfinance providers. The studies suggest several alternative ways of defining or measuring over-indebtedness and various factors of client over-indebtedness.

A borrower can have trouble repaying a loan for various reasons, and these are difficult to predict. Studies on over-indebtedness in the Indian context are mostly region-specific. They extend the understanding about over-indebtedness in two ways. First, they use a definition based on the level of sacrifice made by households. Second, they use household-level data from several mature microfinance markets in the country.

The studies evaluate the level of over-indebtedness among microfinance borrowing households and the factors of over-indebtedness in the Indian microfinance sector.

This household-level study confirms the presence of over-indebtedness. Its level, based on the amount of sacrifices undertaken, is quite alarming, particularly in rural regions. The results bring out the fact that income generation is critical for poor households. If borrowers can find ways to increase their income, they can repay their debt. If households have multiple earning members, it improves the total household income.

Similarly, an entrepreneurial activity lets other household members expand or diversify income. Getting a job or starting a new business with low skill sets is risky and increases the change of income loss. Therefore, the findings of the study suggest that providing credit or loan is necessary but not adequate; it needs to be accompanied with adequate income-generating opportunities.

This builds a strong case for developing a comprehensive plan to improve skill-sets and the level of financial literacy among the borrowers. There is a need for proper training and guidance to improve employability and business managing capability of poor households.

At the same time, the clients should understand their rights and obligations and the long-term implication of having a good credit history. Putting in place such a capacity-building mechanism can prove to be a costly affair for MFIs.

It needs collective effort by the government, social investors, and microfinance institutions. A well designed system of monitoring clients’ repayment capability is also needed to not only help MFIs in detecting over-indebtedness but also in controlling it. The MFIs should own up to this responsibility with due diligence.

The writer is an economist. e-Mail: pradeep25687@yahoo.co.in.