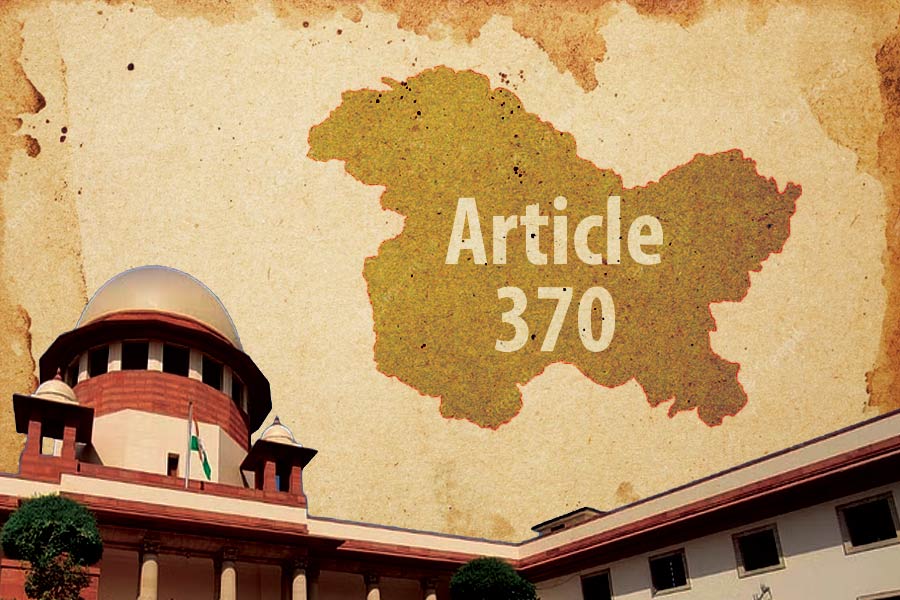

When highly respected former judges of the Supreme Court open their mouths to find fault with some crucial apex court judgements on Central decisions and legislative actions with far-reaching consequences for the country’s democratic system, it is cause for both hope and alarm. For, in recent times the country has experienced with great consternation how the apex court put its seal of approval on controversial government actions which seem obviously detrimental to the social fabric and democratic rights of the people. Yet, not much could be said on such rulings of grave import by laymen since the apex court is always held with awe and respect and any criticism of its judgements is discouraged in various ways. But, when eminent judges sit on judgement of judicial verdicts, which is a rather rare phenomenon, it infuses courage and hope into votaries of civil liberty. This is exactly what former SC judges – Justice Rohinton F Nariman and Justice Madan Lokur – have done lately. Pointing out how the Supreme Court’s five-judge Bench erred in validating the abrogation of Article 370 of the Constitution and consequential reorganisation of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, the opinions expressed by former judges are interesting to note.

Justice Nariman said the Centre’s decision to bifurcate J&K when there was already President’s rule imposed on the state had an ulterior motive. It was to bypass the clause in Article 356 which stipulates such a rule cannot exceed one year unless there is a national emergency or the Election Commission says elections are not possible to be held. Justice Lokur also questioned the imposition of President’s rule in the first place since the Assembly was not dissolved while political parties were pleading with the Governor to be offered a chance to form government. Under Article 356 of the Constitution, if a state government is unable to function according to constitutional provisions, the Union government can take direct control of the state machinery. That may not have been the case in J&K.

The SC validated the abrogation of Article 370 even after declaring that the method in which it had been done was not legally tenable. Justice Nariman also questioned how the Supreme Court could accept an assurance given by the Solicitor General (SG) that statehood will be restored since the SG does not have any authority to bind the successor government. This only would give an excuse to the Centre to delay granting statehood dealing a body blow to federalism in the country.

Justice Nariman went further to examine and explain the threats to democracy posed by the government’s legislation replacing the Chief Justice of India with a Prime Minister-appointed minister in the panel that selects the Chief Election Commissioner and other Election Commissioners. He also pointed out how the functions of a state government are being paralysed and virtually taken away by the Governor, a Central government appointee, with the help of the President.

Justice Nariman chose the occasion of delivering a lecture on “Constitution: Checks and Balances” to articulate how he is feeling “disturbed” by four instances of government-judicial actions from the beginning of the year culminating in the recent judgement on the repeal of Article 370. For the first time the country heard coruscating criticism of four such disturbing actions by a legal luminary. Retired Justice Nariman first lambasted the attack on the media by the government when the latter had banned the telecast of two BBC documentaries on PM Modi’s role as the then Chief Minister in the 2002 Gujarat riots and then ordered tax raids on the media outlet.

Strongly defending the media’s role as a “watch dog” of democracy, Justice Nariman has so cogently stated that whenever there is a tax raid on a media organisation following some expose of government actions by the former, the court should immediately declare such raids as illegal and unconstitutional and stop them. If the media is not defended for its criticism of the government’s acts of omission and commission, it would spell danger for democracy, the judge said. His words are memorable for the survival of democracy: “If our watchdog – media – is killed, then nothing remains.”

Justice Nariman minced no words in slamming the introduction of the Election Commission Bill in the Parliament and passed by the Rajya Sabha. The process has followed a disturbing trajectory. The SC ordered that the Chief Election Commissioner and the ECs should be selected by a panel comprising the PM, CJI and the Leader of Opposition, until the Parliament enacted a law. As if taking a cue from the apex court, the government moved a Bill to replace the CJI by a selected cabinet minister. This, according to Justice Nariman, is “most unfortunate.” The composition of the resulting committee means the government’s view will always prevail and the Opposition’s opinion against the government nominee would be rejected, the voting result being two against one. Already, the EC has been accused by commentators and politicians of acting blatantly in favour of the ruling party at the Centre.

The actions of the Governor of Kerala have come in for criticism for sitting on Bills for months and then referring them to the President. Justice Nariman warned “wholesale reference to the President,” of Bills by the Kerala Governor has the potential to bring the legislative activity of the state to a standstill.

The utterances of the two judges in defence of democracy and federalism are indeed sagacious and welcome.