The demise of China’s popular former Premier Li Keqiang October 27, only 10 months after retiring from a decade in office, has triggered conspiracy theories and an inevitable comparison between his model of China’s economic growth and that of current President Xi Jinping. China watchers smell conspiracy behind his death for two reasons. He died rather too young by Chinese standards at the age of 68, whereas China’s top leaders usually live much longer due to the special health care taken for them. Secondly, the death comes in the wake of a purge of top leaders perceived to have fallen from Xi’s grace. Only a few months back the high-profile Foreign and Defence Ministers both were unceremoniously removed from their positions. This has fuelled speculation about the real cause of Li’s death.

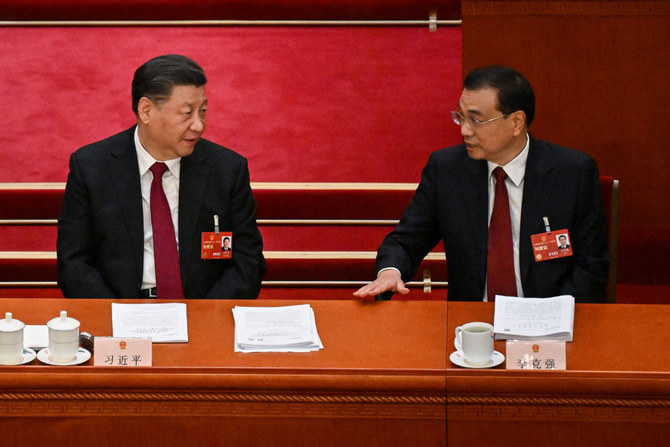

Li was premier and head of China’s cabinet under Xi for a decade until stepping down from all political positions in March. In the top echelons of the government he was an economist of stature among technocrats. His vision of Chinese economic growth on the basis of less government control and reliance on market economy was shared by many leading lights of China as well as a large section of common people. But, he faced roadblock from Xi and his coterie who are staunch followers of state control. As he increasingly became lonely in the party Politburo, his model was also dumped by Xi’s followers. At this stage he almost raised a banner of revolt while laying a wreath in August 2022 at a statue of Deng Xiaoping – the leader who had brought transformational reform to China’s economy. He then vowed: “Reform and opening up will not stop. The Yangtze and Yellow River will not reverse course.”

Video clips of the speech went viral but were later censored from Chinese social media. These were widely viewed as a veiled criticism of Xi’s policies. Earlier, Li had sparked debate on poverty and income inequality in 2020 when he revealed 600 million people in China earned less than the equivalent of $140 per month.

His unexpected death is therefore a significant event as much for the sadness it has caused among the people as for the alternative vision for governing the country that he represented in sharp contrast to his boss Xi’s. No wonder then that the administration under Xi took extreme care to announce his death 10 hours after he breathed his last. Normally, the obituary of a leader of such a stature in China is put out soon after his death. But, in Li’s case, China’s official daily took longer to do so.

However, this did not stop an outpouring of grief in the social media reflecting the popular sentiments for the departed leader. Seemingly alarmed by the development, the authorities immediately swung into action and cracked down on access to a section of social media to stem the tide of condolences for a man once seen as a potential rival to Xi. People posted videos of Li standing in ankle-deep mud, visiting victims of a flood and shared a speech of his promising China would remain open to the outside world.

A widely circulated social media post noted that many Chinese people identified themselves with Li, as they too have struggled over the past decade but have gradually lost ground. It was remarkable the way a closed society like China reacted to Li’s death. People shared quotes attributed to Li, such as “power must not be arbitrary.” This is an oblique criticism of Xi’s leadership.

It is a measure of Li’s courage that he could stand up to Xi not wearing masks at a university programme along with students defying Xi’s severest lockdown diktat during the COVID-19 pandemic. He also encouraged street vendors to sell their products during the pandemic and try to overcome the hardships COVID-19 brought in its train.

With the passing away of Li the possibility of an alternative approach to China’s development is virtually gone. This does not appear to be a good sign for the Chinese economy. International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts released this month show China’s real GDP growth slowing from 5 per cent this year to 4.2 per cent in 2024 and the 3 per cent range in 2027 and beyond. China’s income inequality widened in 2022, in a year when growth clocked in at 3 per cent amid zero-COVID restrictions. Average per-capita disposable income in the top 20 per cent of urban households was 6.3 times that of the bottom 20 per cent, the widest gap in comparable data going back to 1985.