New York: Not just red rocks and craters we saw in the popular science fiction film The Martian starring Matt Damon, Mars has several volcanic rocks composed of large grains of olivine — the muddier less-gemlike version of peridot that tints Hawaii’s beaches dark green, NASA’s rover Perseverance has discovered.

Perseverance landed in the Jezero Crater, a spot chosen partly for the crater’s history as a lake and as part of a rich river system, back when Mars had liquid water, air and a magnetic field.

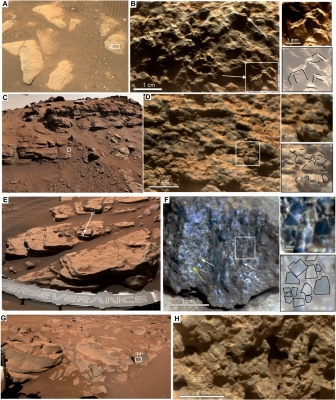

What the rover found once on the ground was startling. Rather than the expected sedimentary rocks — washed in by rivers and accumulated on the lake bottom — many of the rocks are dark green in nature, according to researchers from Purdue University in the US.

“We started to realise that these layered igneous rocks we were seeing look different from the igneous rocks we have these days on Earth. They’re very like igneous rocks on Earth early in its existence,” said planetary scientist Roger Wien in the study published in the journals Science and Science Advances.

Understanding the rocks on Mars, their evolution and history, and what they reveal about the history of planetary conditions on Mars helps researchers understand how life may have arisen on Mars and how that compares with early life and conditions on ancient Earth.

“One of the reasons we don’t have a great understanding of where and when life first evolved on Earth is because those rocks are mostly gone, so it’s really hard to reconstruct what ancient environments on Earth were like,” said Briony Horgan, associate professor in Purdue’s College of Science.

“The rocks Perseverance is roving over in Jezero have more or less just been sitting at the surface for billions of years, waiting for us to come look at them. That’s one of the reasons that Mars is an important laboratory for understanding the early solar system,” he added.

The rocks and lava the rover is examining on Mars are nearly 4 billion years old.

Rocks that old exist on Earth but are incredibly weathered and beaten, thanks to Earth’s active tectonic plates as well as the weathering effects of billions of years of wind, water and life.

On Mars, these rocks are pristine and much easier to analyse.

Scientists can use conditions on early Mars to help extrapolate the environment and conditions on Earth at the same time when life was beginning to arise.

“From orbit, we looked at these rocks and said, ‘Oh, they have beautiful layers!’ So we thought they were sedimentary rocks,” Horgan said.

“And it wasn’t until we were very close up and looked at them, at the millimeter scale, that we understood that these are not sedimentary rocks,” he added.