Los Angeles: Researchers have discovered that a microprotein called PIGBOS found in the powerhouse of the cells — mitochondria — contributes to mitigating stress happening within the cells — an advance that may lead to better understanding of disease conditions like cancer.

The researchers, including those from the Salk Institute in the US, said that while an average protein molecule present in the human body has around 300 chemical units called amino acids, the microproteins had fewer than 100 of the building blocks.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, noted that PIGBOS was made of 54 amino acid molecules, and indicated that the microprotein could be a target for cell stress based human diseases like cancer and neurodegeneration.

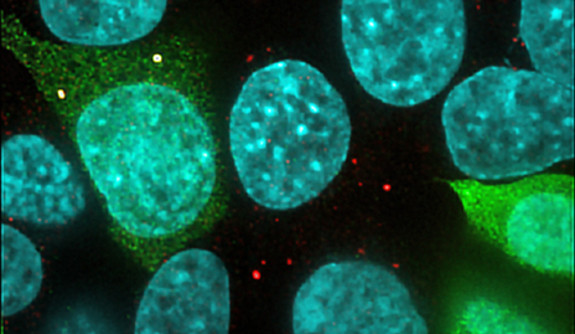

Usually to track and find the functions of proteins, researchers attach a jelly fish derived probe called the green fluorescent protein (GFP) to them, which glows and indicates the protein’s presence in cells, the study noted.

However, the researchers of the current study ran into a roadblock when they tried to mark PIGBOS with GFP as the microprotein was too small relative to the size of the fluorescent tag.

They solved the problem using a less common approach called split GFP where they fused just a small part of GFP, called a beta strand, to PIGBOS.

With the new set up, the researchers could see PIGBOS, and study how it interacted with other proteins.

As they mapped the microprotein’s location, they found that it sat on the outer membrane of the mitochondria and made contact with proteins on other organelles.

PIGBOS interacted with a protein called CLCC1, which, the researchers said, is part of a cell organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum (ER).

“PIGBOS is like a connection to link mitochondria and ER together,” said study co-author Qian Chu from the Salk Institute.

According to the researchers, PIGBOS communicated with CLCC1 to regulate stress in the ER.

“We hadn’t seen that before in microproteins–and it’s rare in just normal proteins,” Chu said.

The study noted that without PIGBOS, the ER is more likely to experience stress and form misshapen proteins.

The researchers said that this may lead to the cell trying to clear out the irregular proteins, failing which it may initiate a self-destruct sequence and die.

According to Chu and his team, it was unusual to see a mitochondrial protein playing a role in the unfolded protein response.

They added that the new understanding of PIGBOS could open the door for future therapies targeting cell stress.

“Going forward, we might consider how PIGBOS is involved in disease like cancer,” said Chu.

Chu said that the ER is more stressed in cancer patients than in a normal person, and added that ER stress regulation could be a good target to tackle the disease.

PTI