Sujata Kumari Muni

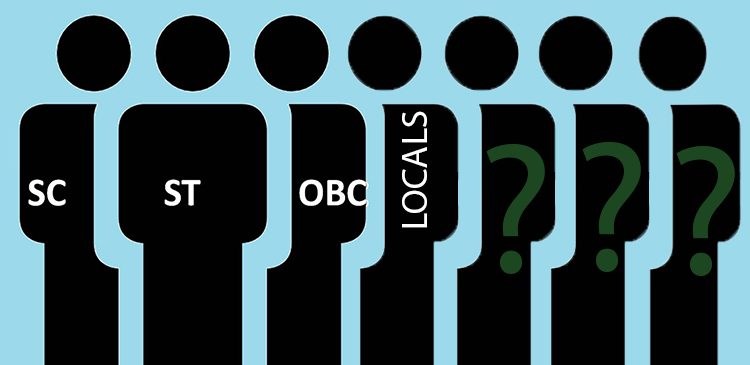

Andhra Pradesh, in a first, enacted a law guaranteeing 75 per cent reservation in jobs for locals in private industrial units, factories and joint ventures, including public-private partnership concerns. The enactment adds that if locals lack requisite skills, companies and factories must train locals with the state government’s assistance and hire them.

Fact is, no state can afford to ignore local talent; but shutting the doors to migrant labour force is regressive. This operating model will prove to be more complex and threaten the overall economic and industrial growth of the newly formed state. Of late, many regional satraps are stuck by exclusivity and narrowness endearing parochial consideration or jingoism in mind. This mindset is dominating our political landscape and instances are galore of state governments such as the one in West Bengal dictating preference for Bengali-speaking people over non-Bengalis in employment and Gujarat CM Vijay Rupani promising 80 per cent reservation in jobs for Locals in the industrial and services sector; many other states may follow suit.

According to Census 2011, there are 139 million internal migrants in the country and these are a captive source of labour. Their employment helps them earn and contribute to state GDP. The xenophobic reaction and nativism are often used as an excuse to hide failures of delivery by governments and utter misgovernance.

Sub-nationalism and overindulgence in domestic politics of parochialism are greatest threat to regional peace and stability among states. India suffers from Parochialism which is often trumped by ethnic differences or provincial solidarities. It is nothing but splitting the general population into groups and putting the needs of natives of their own states ahead of those in other states.

These human-raised barriers are not created overnight. They evolve over a brief period. They are backed by selfish and personal goals at the expense of national interests.

Enacting laws that support such interests are violative of Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution. Article 19(d) and 19(e) of the Constitution guarantee freedom of movement to Indian citizens within India. In the past, many Indian states have enacted such laws but never implemented it rigorously. Interestingly, Andhra Pradesh has excluded areas such as fertilisers, coal, pharmaceuticals, petroleum, cement and IT Industry from the ambit of its job guarantee. Similarly, while formulating the 100 per cent reservation plan for Kannadigas in blue-collar industries in Karnataka, both infotech and biotech were kept outside their purview. However, no such local reservation has been challenged in any court of law and the Indian constitution contains no provision for non-discriminatory commercial clause. While responding to the changed law, corporates will be busy adjusting the composition of workforce to be quota compliant. However, the number and nature of jobs will remain unaffected. Hence, states must focus more on new job creation.

At a time when Indian states are fiercely competing to attract investment, it would be counter-productive for these states to have discrimination and reservation for sons of the soil. States that roll out such obstacles will lose in the long run, since investments come when compliance costs are low and freedom of hiring employees is high.

To achieve higher growth rate in an economy, there is no substitute to employment of the skilled and challenging professionals. Further, to survive and excel in a globalised world, the country should focus on overall skill development and national goals over regional preferences. The politics of local preference and local defence will dilute the pace of economic growth.

No state can afford to ignore local talent, but shooing away skilled or unskilled migrants is a regressive step. The political compulsions and electoral promises made by politicians are obvious but reservation for natives in the private sector is not an effective model to tackle unemployment and underemployment. Internal migration is of labour is natural as India is a labour surplus country. Many studies have indicated that movement of labour is good for the economy as regions suffering deficit can import labour from surplus states.

The writer is an advocate, with practice at the Supreme Court of India.