SN Misra

The NDA has ensured passage of the Citizenship Amendment Bill in both houses of parliament despite its lack of majority in the Rajya Sabha. The Bill (now Citizenship (Amendment) Act, or CAA) grants citizenship to those Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians who illegally settled in India till March 31, 2014. The Act aims to treat those persecuted in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan on par with Hindus in India, who are citizens according to the Citizenship Act, 1955. It also reduces residency requirement for such illegal migrants from 11 to five years. According to an assessment of the Intelligence Bureau, there are 31,131 such illegal migrants, of whom 25,447 (81 per cent) are Hindus and 5,807 are Sikhs.

The Act, however, excludes other persecuted Muslim communities such as the Shia and Ahmadiyya in Pakistan. It also does not include refugees from Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan. The Rohingya, in particular, who are subject to severe persecution are not covered by the Act.

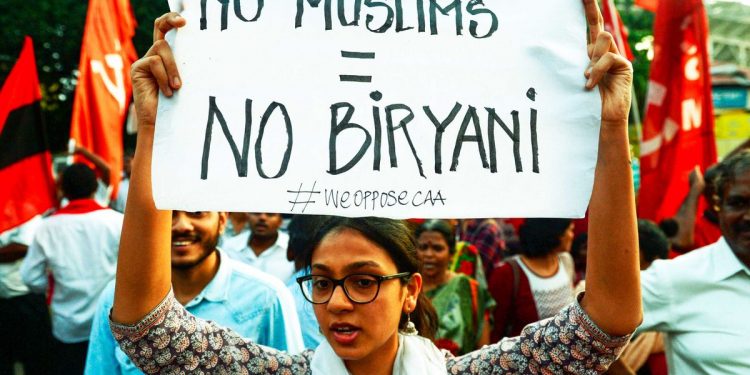

The amended Act strikes at the root of the basic structure of the Constitution, that is, Right to Equality (Article 14) and secularism which has been part of the preamble to the Constitution since 1976. The exclusion of Muslims as a community attracts violation of Article 15, which prohibits discrimination of people on the basis of caste, sex and religion.

The government believes the Bill will pass through the Supreme Court as well, as the state has adopted the principle of intelligible differentia. Harish Salve, the redoubtable lawyer, believes the Act will not attract Article 14, as people coming from other countries cannot be confused with people within India’s territory. However, such an argument would not hold water if one peruses key judgements of the Supreme Court, where they have interpreted the principle of intelligible differentia.

The principle derives from two clauses: First, equals can be treated differently if they can be grouped based on clear differentiation, and second, it is possible to find a nexus between the basis of classification and object of an Act. For instance, Army personnel are covered under the Army Act, which is different from legal provisions applicable to civilians. The objective of such differentiation is to ensure that the defence services are not allowed to strike and preserve the security and integrity of the country.

The court has also struck down many cases where such differentiation has not been found to be reasonable. A case in point is the liberalised pension scheme, which applied to pensioners retiring after January 31, 1979, and not to those who retired prior to that date. In the DS Nakara vs Union of India (1982) case, the court held that dividing a homogeneous class such as pensioners on a cut-off date was irrational and had no relation with the objective of paying liberalised pension. Earlier, when Maneka Gandhi was not allowed to travel abroad (Maneka Gandhi vs Union of India case, 1975), then Chief Justice of India PN Bhagwati asserted that equality before law and its differentiation cannot be based on arbitrary decision-making or caprice.

In light of the above, the government’s decision to classify Muslims as a separate category of immigrants and keeping neighbouring states such as Myanmar, Nepal, Bhutan and Sri Lanka out of its purview is blatantly arbitrary and discriminatory.

The court has observed from time to time that while it permits classification within a group based on reasonable differentiation, it prohibits ‘class legislation’, that is, legislating for a particular class, caste or religion while excluding others from the purview. The Act also runs counter to Section (5) of Assam Accord (1985), which made no distinction between immigrants on the basis of religion, while fixing a cut-off date.

It is known that the politics of demography, national identity, cultural nationality is high on the agenda of the BJP. After scrapping Article 370 and getting a favourable judgement on Ram temples at Ayodhya, the government is paying scant attention to serious economic issues such as growing unemployment and economic insecurity. The present attempt is a handy smoke screen to divert political attention from real and serious livelihood issues to encouraging communal polarisation, with an eye on getting political dividend in states such as West Bengal, where Muslims constitute 25-30 per cent of the population.

Professor Thomas Piketty and the Nobel Laureate Professor Abhijit Banerjee, in a perceptive article published in ‘EPW’ March 2019, bring out how elections in India from 1962-2014 have been driven on the plank of caste identity and religious conflict rather than key economic challenges of providing effective access to high quality public services such as education and healthcare to all, irrespective of caste or religion.

It is surprising that a party such as BJD, which parted company with the BJP in 2009 citing communal practices by BJP, has also thrown its political weight behind the Act. Politics, it is said, is the art of the possible, but it is indeed a sad commentary that sectarian politics is getting precedence over core concerns of ‘socio-economic justice’, which is a major plank of our preamble. While the number of immigrants involved in this exercise is minuscule, it has a much larger political message, namely that majoritarianism would trample upon minority rights.

Justice Srikrishna, who gave a report on data protection law, was dismayed enough to state after the data protection Bill was passed that it could “turn India into an Orwellian state”. In his magnum opus ‘Animal Farm’ George Orwell had observed that in a communist state, “some are more equal than others”. India seems to be passing through such a dystopic moment, where equality before law and secularism are facing a crisis under dubious cover of reasonable differentiation. National security has become a shenanigan for minority bashing and the multicultural ethos of India is getting seriously dented.

The writer teaches Constitutional law.