Though in Odisha Biju Janata Dal (BJD) has been the dominant political force for the last two decades, as our previous analysis of change in vote share showed, elections in the state have gotten more competitive. The ruling party’s share of votes has either receded or stagnated over the last couple of elections, while BJP, though struggling, has made some gains, especially in general elections.

Further analysis of election data from Ashoka University’s Trivedi Centre for Political Data (TCPD) reveals that the increase in competition is also reflected in increase in the number of contesting candidates and the shrinking margin of victory.

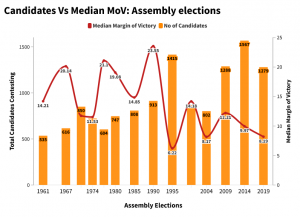

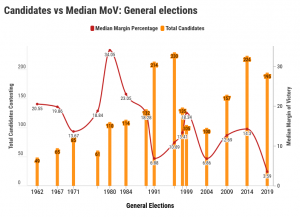

In 1974, when the strength of the (sixth) Assembly was increased from 140 to 147, a total of 722 candidates contested for those 147 seats. But by 1995, that number had almost doubled to 1,415. In 2014, the total number of candidates contesting for 147 seats was 1,567, the highest ever. The trend also holds true for the general elections with the number of candidates contesting almost doubling from 110 in 1980 to 224 in 2014.

Also read: BJD dominance continues, elections get more competitive

As a consequence, the average number of candidates fighting for an Assembly seat has risen significantly. In 1974, that number was 5, but in 1995, it was 10, in 2014, 11, and in 2019, 10. So, a candidate at the constituency level now has double the number of competitors than he had in 1974.

Voters are more judicious today as they are better informed about the candidates’ assets, education and criminal background. The introduction of NOTA has also given them the opportunity to express their discontent

Ranjan Kumar Mohanty | State Coordinator of ADR, Odisha Election Watch

Elections have become more competitive, agrees Ranjan Kumar Mohanty, state coordinator of Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) Odisha Election Watch. “Money definitely plays a role but there is also increased transparency in elections now that the candidates have to file affidavits,” he says.

“Voters are more judicious today as they are better informed about the candidates’ assets, education and criminal background. The introduction of NOTA has also given them the opportunity to express their discontent,” he says.

Tight fight

Another measure of electoral competitiveness at the state and the constituency level is the median margin of victory (median MoV). Margin of victory (MoV) refers to the difference of votes between the winning candidate and the runner-up in a constituency.

Margin of victory, as a percentage of total valid votes in a constituency gives the margin percentage, interpreted as the winner getting ‘x’ per cent more votes than the runner up. And when the margin percentages for all constituencies of the state are lined from the smallest to the largest and the middle value is picked, it’s called the median margin of victory. Simply, the less the median MoV in an election, the more competitive it is, because a small margin signals fierce competition.

For assembly elections, the Median MoV has been getting smaller and smaller, from 12.21 per cent in 2009 to 9.97 in 2014, and 8.19 in 2019, reflective of a more competitive electoral landscape. The pattern is even more exaggerated for general elections, where the median MoV was lowest in 2019, signaling cut-throat competition between top two rivals.

However, the rising competition seems to be having little threat to BJD. Political observer and former professor of political science at Utkal University Surya Narayan Misra says it’s too early to say anything about elections next year, but he adds, “For BJD, the margin may go down from 25,000 to 13,000. But the party will win 100+ seats and in no way it is going to lose majority given their strategy and strength.”