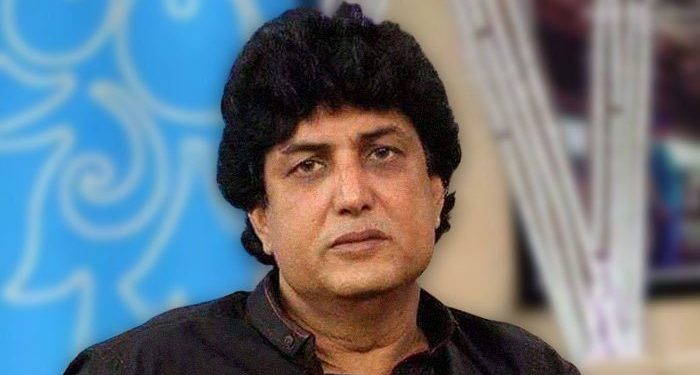

Lahore: He calls himself ‘Pakistan’s biggest feminist’, but soap-opera writer Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar sparked a national row this week after he hurled abuse at a women’s rights activist on live television.

The invective-laden diatribe came just days before thousands of people are expected to march in cities across Pakistan to mark International Women’s Day, adding fuel to growing calls for greater freedoms in the ultra-conservative nation where pushback against such demands can sometimes be vicious.

Qamar’s tirade targeting activist Marvi Sirmed quickly went viral, highlighting Pakistan’s acrimonious conversation around women’s rights and cultural values.

While appearing on a television panel to discuss the upcoming Aurat (women’s) march, Qamar took aim at its slogan, ‘My body, my choice’.

He told Sirmed that ‘no one would even spit on your body’ — adding she was a ‘cheap woman’ who should ‘shut up’.

Reaction was swift, with local media giant Geo Entertainment — which recently signed Qamar to write soap operas — suspending his contract, while politicians and celebrities condemned him on social media.

Drama critic Sadaf Haider told AFP that Qamar held ‘deeply misogynistic’ views that he wove into his soaps, arguing that such narratives are ‘not helping the cause of women’s rights’ in Pakistan.

Qamar declined repeated requests for comment, though he has appeared on other talk shows and refused to apologise, blaming Sirmed for interrupting him on air.

Pakistani soaps have been criticised for their depiction of female protagonists — often damsels in distress silently accepting abuse from their in-laws and husbands, and that is shown as a strength.

Female villains are usually the opposite: they do not want to settle down, do not want to conform and end up creating problems by seducing the virtuous heroine’s husband.

While Qamar has come under fire for the negative portrayal of women in his soap operas, his latest work, “Meray Paas Tum Ho” (“I have you”) broke viewership records in Pakistan.

The ‘my body, my choice’ slogan during last year’s event generated criticism in a Muslim country largely unaffected by the global #MeToo movement.

Organisers and participants were accused of promoting Western, liberal values and disrespecting religious and cultural sensitivities.

Some of the more provocative posters and slogans from the march discussing divorce, sexual harassment and menstruation drew a quick backlash and a slew of threats against the organisers.

Last month, anti-march campaigners filed a petition in Lahore to block this year’s event, which is set for Sunday.

Lawyer Azhar Siddique alleged it is being funded by ‘various anti-state parties’ with the aim of sowing ‘anarchy’ in society.

The judge ruled that a ban would be unconstitutional, but warned marchers to refrain from spreading ‘hate speech and immorality’.

A separate petition in Islamabad calling for a ban on the march was also dismissed Friday.

Nighat Dad, part of the Aurat march organising committee, was unfazed by the backlash to previous events.

“In reality, men like Khalil-ur-Rehman Qamar are threatened, which is why they are coming up with all kinds of ridiculous arguments against the women’s movement,” she told AFP.

Women have long fought for basic rights in Pakistan, where activists often face harassment and threats for the work they do.

Sirmed, the activist, is known to have received multiple death threats.

In 2012, she escaped unharmed when unknown assailants fired upon her car. Her home was ransacked in 2018 and her laptops, passport and other travel documents were taken.

Amnesty International expressed support for the Aurat march, saying in a statement that the ‘horrific threats of violence, intimidation and harassment of the marchers must stop’.

Much of Pakistani society operates under a strict code of ‘honour’, systemising the oppression of women in matters such as the right to choose who to marry, reproductive rights and even the right to an education.

According to estimates by the Honour Based Violence Awareness Network, at least 1,000 women fall victim to honour killings in Pakistan each year.

Pakistan ranked a dismal 136 on the UN Development Programme’s Gender Inequality Index in 2018, doing worse than most of its South Asian neighbours.

AFP