Djoomart Otorbaev

I still have vivid memories of my first trip to Turkey in 1993. After the Soviet Union’s collapse two years previously, we Kyrgyz gained access to a world we had hitherto only imagined. We all had Turkish relatives somewhere in the West with whom we had lost contact. And there was a similar emotional reaction on the Turkish side: Turkey was the first state to recognise the independence of my country and the other Soviet Central Asian republics.

So, when I arrived at Atatürk airport in Istanbul, I approached ordinary Turks and tried to speak with them. To my disappointment, we didn’t understand each other. I realised that although many elements of our respective languages were similar, differences in pronunciation and the many Persian, Arabic, and Latin words that had become a part of modern Turkish prevented me from communicating freely with the people I met. Despite a shared culture and traditions, history had separated Turkic-speaking people not only geographically and linguistically but also in essence.

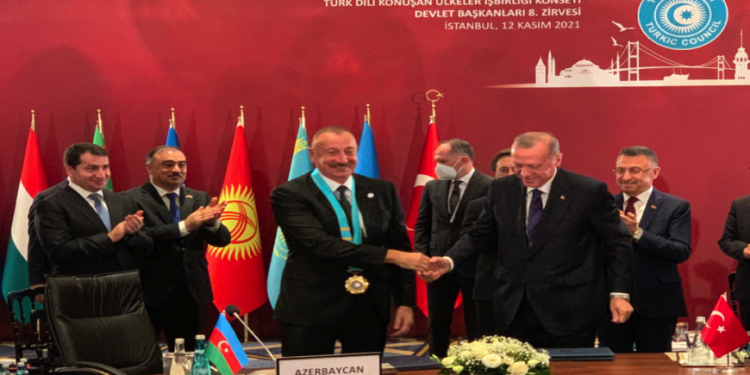

But a gradual cultural rapprochement has taken place in the 30 years since the ex-Soviet Turkic states gained independence, and major powers are increasingly taking note. The latest step came at a summit in Istanbul in November, when the seven members of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States – Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, plus Hungary and Turkmenistan as observers – renamed themselves the Organisation of Turkic States.

The OTS spans 6,149 kilometers from Hungary to Kyrgyzstan and has a combined population of over 170 million and an aggregate GDP of over $1.3 trillion. In Istanbul, the assembled leaders proclaimed that an alliance based on deep roots, kinship, brotherhood, and political solidarity would guide cooperation in economic development, trade, and investment. The countries pledged to pay special attention to strengthening their cultural and humanitarian ties.

It is no secret that Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan wants to turn Turkey into a pivotal regional player. To realise this goal, the country could pursue one of three models: pan-Islamism, neo-Ottomanism, or pan-Turkism. With pan-Islamism, the Turks have serious competitors in Saudi Arabia and Iran. Neo-Ottomanism is untenable, because Turkey has lost its influence in its former European and Asian territories. But when it comes to pan-Turkism, the country has no rivals. For example, Turkey recently cemented its special relationship with Azerbaijan by actively supporting it in its 2020 war with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh.

So far, there is no sign that Turkey is seeking to dominate the Turkic world, and even if it wanted to, the Central Asian states have too much geopolitical room for manoeuvre. Because the region is now a playground for three global powers – Russia, China, and the United States – the Central Asians are able to play them off against each other.

All states build partnerships to promote their domestic and foreign priorities. And because the Central Asian countries value their multi-vector orientation, they will not put all of their diplomatic eggs in one basket. Instead, they will continue to cooperate with Russia for historical reasons, China for economic investment, and the US for security.

Erdoğan, a realist at heart, no doubt understands this, and will not seek to reorient the other Turkic countries exclusively in Turkey’s direction. He is playing for more regional influence, not necessarily exclusive leadership.

Russia seems to grasp this reality, and may even seek full OTS membership. Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has said previously that, “I see no problems with us joining this organisation.” And strengthening cooperation between the ex-Soviet Turkic states and Turkey may also strengthen Turkey’s bilateral relationship with Russia. Some even speculate that Turkey, instead of trying to join a European Union that has barred its door, will instead opt for the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union, joining Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan (Uzbekistan is an observer).

For its part, China has been studiously silent on the new Turkic union. But the Global Times recently published a commentary about the OTS that may well have expressed the Chinese government’s fears. “This organisation,” the newspaper said, “may trigger the rise of extreme nationalism, which could intensify ethnic conflicts and hit the regional stability and security.”

Moreover, it added, “There are also groundless sayings that Uyghur people in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region are of the same ethnic group as Turks. […] China should remain vigilant against the spread of pan-Turkism and pan-Islamism that the Organisation of Turkic States may bring about.”

The plight of the Uyghur minority, a Turkic ethnic group in Xinjiang province, is undeniably a sensitive issue for China. But if the OTS serves to reinforce and deepen regional economic ties and thus strengthen Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, it is likely to turn a blind eye to what China does in Xinjiang.

The West, meanwhile, has so far said little about the OTS. But with the Eurasian chessboard becoming increasingly pivotal as great-power competition heats up, it is unlikely to remain silent for long.

The writer is a former Prime Minister of Kyrgyzstan. ©Project syndicate