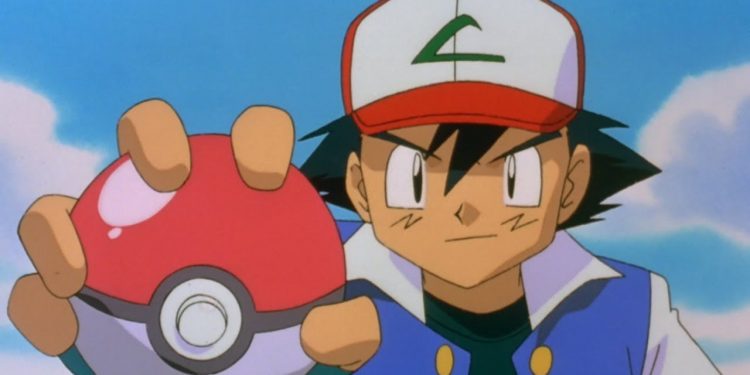

Boston: People who spent countless hours playing Pokemon videogames in their childhood have a specific brain region that activate when they see images of their favourites characters such as ‘Pikachu’ or ‘Charizard’, scientists in Stanford university here have found.

The findings, published in the journal ‘Nature Human Behaviour’, help shed light on two related mysteries about our visual system.

“It’s been an open question in the field why we have brain regions that respond to words and faces but not to, say, cars,” said Jesse Gomez, a graduate student at Stanford. “It’s also been a mystery why they appear in the same place in everyone’s brain,” said Gomez.

A partial answer comes from recent studies in monkeys at Harvard Medical School. Researchers there found that in order for regions dedicated to a new category of objects to develop in the visual cortex – the part of the brain that processes what we see – then exposure to those objects must start young when the brain is particularly malleable and sensitive to visual experience.

While wondering if there was a way to test whether this was also true in humans, Gomez recalled his own childhood and the countless hours he spent playing videogames, and one game in particular – Pokémon Red and Blue.

Gomez reasoned that if early childhood exposure is critical for developing dedicated brain regions, then his brain – and those of other adults who played Pokemon as kids – should respond more to Pokemon characters than other kinds of stimuli.

The first Pokémon game was released in 1996 and played by children as young as five years old, many of whom continued to play later versions of the game well into their teens and even early adulthood.

Researchers recruited adults who had played Pokemon extensively as children. When the test subjects were placed inside a functional MRI scanner and shown hundreds of random Pokemon characters, their brains responded more to the images compared to a control group who had not played the videogame as children.

The site of the brain activations for Pokémon was also consistent across individuals. It was located in the same anatomical structure – a brain fold located just behind our ears called the ‘occipitotemporal sulcus’.

The findings are just the latest evidence that our brains are capable of changing in response to experiential learning from a very early age, but that there are underlying constraints hardwired into the brain that shape and guide how those changes unfold.