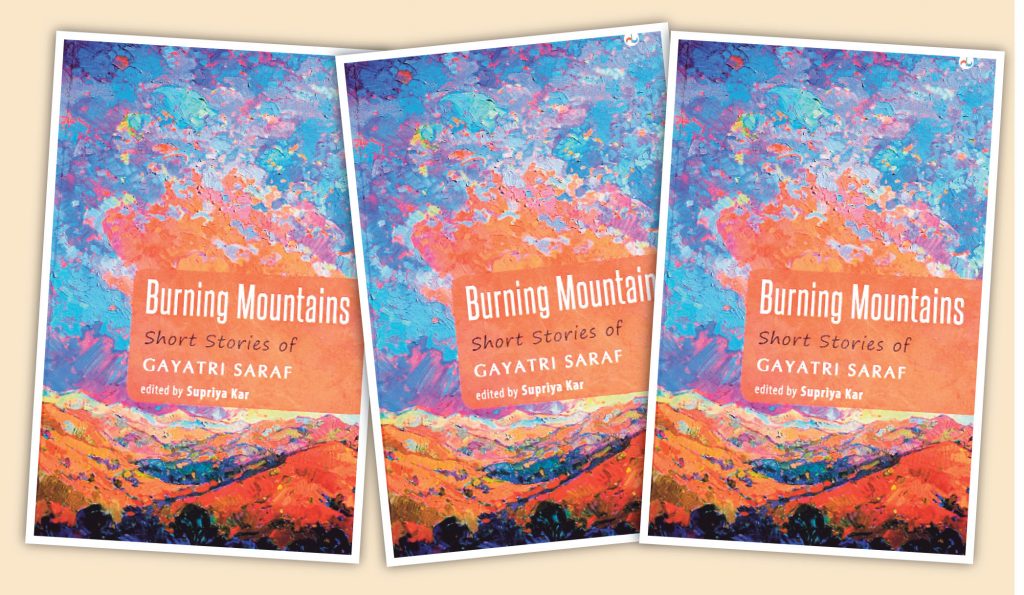

Gayatri Saraf’s Burning Mountains is a compilation of her 14 critically acclaimed Odia stories, translated into English. Recipient of the Central Sahitya Akademi award for her anthology of short stories – Itabhatira Shilpi – in 2017, Gayatri has also bagged the President’s medal for teaching in 2004.

The translation of the cover story Burning Mountains, which was first published in South Asian Review in 2009, amplifies the plight of bonded labourers of Odisha who are trafficked to the brick kilns of Andhra Pradesh. While the Odia labourers toil hard across the day, the modesty of their women is outraged by brick kiln contractors and their henchmen at night. Newspapers replete with such sordid tales of poverty, exploitation and hunger go into the creative process of Gayatri’s fiction wherein penury coerces women of Bolangir and Kalahandi to sell their children for paltry sums of money. The story takes its cue from a real life situation reported in the media some years ago. The situation has not changed a wee-bit today even as politicos advocate alleviating the backward regions. But, none has done anything substantial to curb labour migration from Odisha.

Ironically, Ukia is the representative protagonist and a victim of the despondent social system in Gayatri’s Burning Mountains. The author essays to trace the extinct clan of Ukias from among a myriad of hungry women who sell their babies for food:

“Did she hide herself in the heaps of papers? Where she could go? She’s there, she exists. She exists as a terrible truth. She exists in the dry, cracked earth of villages among the burning mountains; she’s in the desperate cries for food and water. Our eyes don’t have the clarity to see everything. We, therefore, conveniently declare that she doesn’t exist…”

The story titled Artist of the Brick Kiln incorporated in this volume has been transcreated from her award-winning book. The background theme of the story is again the transmigration of farm labourers from Odisha to the brick kilns of the neighbouring state where torture, humiliation and a life bereft of human rights greet them. Poverty drives a family of three innocent villagers to fall into the trap of a labour contractor. The lure of rich life in distant hills entangles the Odias who end up toiling hard in kneading lumps of fly-ash into making bricks somewhere in Andhra Pradesh. The author’s delineation of the sad plight of Odia dadans can be surmised as follows:

Here the laughter of women and there a wailing could be heard. In the midst of all this were the three helpless creatures. Their courage was failing, despite that they trudged on stealthily. Oh God! Where’s the end of this kiln? Oh god save us, oh hills, oh spring, oh witches help us…!

The concluding piece of the volume, Spring of Innocence is a bizarre story of a child’s self-respect. Translated by Supriya Kar, the story showcases a schoolgirl’s sense of propriety and discipline at a school event where she refuses to partake lunch as she had not been issued a lunch coupon. She excuses herself from a queue and wouldn’t even take food without a coupon ignoring the DEO’s request.

“The girl did not budge. She remembered her parents. They didn’t have a BPL card. Her father didn’t go and stand in a queue in front of the ration store. Her mother didn’t have a health card; she didn’t stand in a queue to get benefits from the government health centre. Here a token was required to have one’s meal. How could she stand in the queue without the required token?’’ This sketchy narration brings to light the whole gamut of social deprivation the child undergoes.

Colours of a Butterfly, Basumati is No more and India that is Bharat are among the best stories with substance in this volume. The Odia stories have been translated with great care to retain the spirit of the text. And they read like original English.

RAMESH PATNAIK,OP