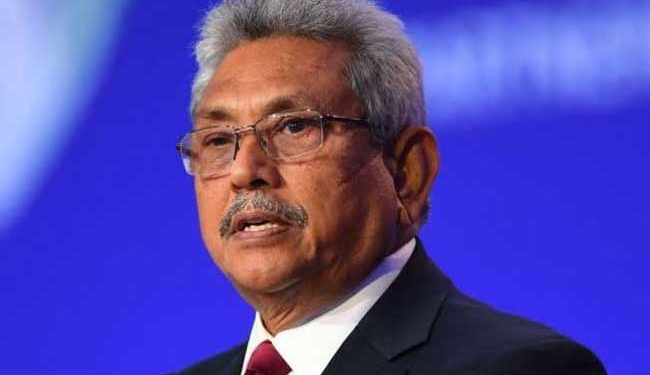

The news that Sri Lanka’s former President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, who fled the country after mass protests and resigned soon after, is expected to return home has baffled many. Cabinet minister Bandula Gunawardana has given a broad hint telling the media, “To my knowledge, he is expected to come back.” Gotabaya and his wife quietly boarded a military jet under cover of darkness after protesters had taken over his house and Presidential offices. They first flew to the Maldives and then to Singapore where they have been allowed to stay on a short visitor’s visa. Many thought Gotabaya would not set foot on Sri Lankan soil again at least for some time to avert possible prosecution for accusations of corruption and war crimes that date back over a decade. As long as he remained President, he enjoyed immunity from prosecution. Now that he is no longer in office, efforts have begun to probe the charges against him and arrest him. Calls are heard on the streets of Sri Lanka demanding he and his family be tried.

There has been much speculation on the whereabouts and final destination of Rajapaksa. The confirmation by the Sri Lankan minister has somewhat set it at rest, but triggered fresh conjectures about his motive. Singapore authorities also clarified that Rajapaksa has not applied for asylum and his visitor’s visa has been extended till August 11. His decision to return to Sri Lanka seems to have been prompted by the fact that he has few other options now as human rights groups and lawyers have been pressuring countries, including the US, not to accept him and help the process of law to try him for his alleged war crimes against Sri Lankan Tamils. Many of his political opponents too were brutally tortured at his behest and taken away, never to return home.

A rights group – South Africa-based International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP) – which documented alleged abuses in Sri Lanka by Gotabaya, has filed a criminal complaint with Singapore’s Attorney General, seeking his arrest for his role in the island nation’s decades-long civil war. The complaint states Rajapaksa committed serious breaches of the Geneva Conventions during the 25-year-long civil war when he was the country’s chief defence official. The civil strife ended in 2009. Rights groups, however, accused both sides – the government and the rebel group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elaam (LTTE) – of abuses during the war. The alleged war crimes by Gotabaya and the armed forces as listed by the rights group include murder, executions, torture, inhuman treatment, rape and other forms of sexual violence, deprivation of liberty, severe bodily and mental harm and starvation. In September 2008, Gotabaya ordered the immediate withdrawal of the United Nations and relief agencies from the war zone so that there would be no witnesses to the carnage perpetrated on Tamil civilians by the Sri Lankan army. The charges form the basis of the legal complaint.

The question is why Gotabaya is apparently keen on returning to Sri Lanka to face such grave charges along with those of corruption and financial irregularities. The answer could be that he, probably, thinks it would be better for him to face trial in his own country than on foreign soil as the ITJP is trying, taking advantage of the absence of immunity he has so long enjoyed as Sri Lankan President. Moreover, the new President, Ranil Wickremesinghe, and several ministers are known to have close links with him. The legal process may be short-circuited with the help of such friends in his own country. Law’s delay is proverbial and endemic almost everywhere. Sri Lanka is certainly no exception.