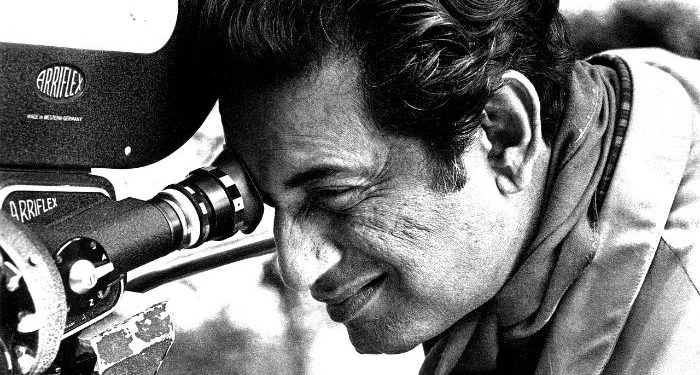

Anwesh Satpathy

In a review of Satyajit Ray’s ‘Apur Sansar’ (The World of Apu), the critic Dwight MacDonald castigated Ray for being “self-conscious.” MacDonald, along with many western critics of that time, didn’t consider Ray capable of handling the complexities of city life. This was because his movies were seen as being autobiographical and reflective of Ray’s own lived experience in India. This attitude stemmed from a stereotypical view of India, the lack of familiarity with its popular culture as well as its city life.

To a contemporary film critic or even someone with a cursory familiarity with Ray, this suggestion is laughable. Not only because his later work, in particular the Calcutta trilogy, dealt explicitly and brilliantly with alienation that came with capitalism but also because his lived experience was as far away from rural life as possible. Born in a family of scholars, Ray grew up in the cosmopolitan city of Calcutta. He was reluctant to study at Shantiniketan due to its “intellectual second rated-ness.” He sought to become a filmmaker after watching Vittorio de Sica’s Italian neo-realist movie ‘The Bicycle Thieves.’ It was the French director Jean Renoir who encouraged him to make ‘Pather Panchali.’

In other words, Ray was as cosmopolitan as it gets. It is no wonder that his portrayal of city life was accurate. It is, however, worth asking as to why his portrayal of Indian rural life strikes a chord even today.

To answer this, we need to grapple with Ray’s critique of commercial Indian cinema. In an interview with Pierre-Andre Boutang, Ray claimed that the Indian audience who are mostly exposed to Hindi commercial cinema were “backward and unsophisticated.” At first glance, this might appear a bit snobbish but Ray’s essays on filmmaking provide a more nuanced view.

Cinema started out as an international medium. Through the technique of mime, the likes of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton created an art-form that was universally accessible. With the development of technology and the introduction of talkies, mime no longer retained the centrality that it did in silent films. Dialogue and visual forms became more essential. This led to the development of distinct national styles in different countries. The Americans developed a Jazz-like tempo along with the nostalgia and sentimentality present in the blues. The French were more experimental, with musicians like Darius Milhaud making extensive use of polytonality popularised by Stravinsky in soundtracks and filmmakers like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut exploring existentialism and Marxism, often questioning the importance of cinema itself.

Indian cinema, on the other hand, has been devoid of such development as a rule. Indian movies have largely been formulaic. They fail to convey or display the rich heritage of literature, music, culture, painting or even geography that we have. In Ray’s words, Indian cinema has “remained as incongruous and clashing elements, refusing to coalesce into the stuff that is cinema.”

Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’ marks a remarkable and conscious departure from the conventions of Indian commercial cinema. While acutely aware of Western art forms, Ray consciously decided to make movies that were, in his own words, “distinct and indigenous.” Ray’s realism is derived from the works of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay. He remains true to the spirit of humanism and lyricism that characterises Bibhutibhushan’s novel. Ray even credits Bibhutibhusan for the pictorial aspect which plays an essential role in turning the movie into a truly indigenous one. As Darius Cooper has argued, Ray’s narratives strongly reflect the principles of Rasa elaborated by Bharata Muni and Abhinavagupta. A sense of epiphany of wonder and constancy of character is ever-present in The Apu Trilogy. For instance, Apu’s character retains constancy though aspects of him change subtly with life’s experiences. This constancy is made obvious to the viewer through contrast with his sister Durga in ‘Pather Panchali’ and his mother in ‘Aparajito.’

Ray’s quest to develop a form of cinema true to Indian experience can also be seen from his use of music. Though manifest most explicitly in ‘The Music Room’ (Jalsaghar), glimpses of it are present even in ‘Pather Panchali.’ Composed by Pandit Ravi Shankar, the soundtrack of the movie almost exclusively uses Indian instruments and classical music. However, it was on Ray’s request that Chunibala Devi (the 80-year-old playing Indir Thakrun) sang the iconic plaintive traditional song. The song wasn’t chosen but was one that Devi had remembered. The song haunts the viewer, especially as it plays in the background when the character of Indir Thakrun dies (made more haunting perhaps with the apt lyrics “Hari, the day is gone and night has fallen. Help me to pass over”).

Dissatisfied with the “spasmodic injection of song numbers” that continues to characterise many Bollywood movies, Ray decided to make the musical ‘Jalsaghar.’ This can be considered at once a critique of the use of music in commercial movies as well as a complete expression of what cinema can achieve. Ray documents the breakdown of the feudal system and the loss of prestige of the hedonistic landlord by making extensive use of Ustad Vilayat Khan’s compositions. It was one of the only films of its time which not only used music thematically but also incorporated extensive classical music.

Ray’s legacy, apart from his technical achievements and fierce originality, was the fact that he showed Indian filmmakers and artistes what cinema can be. Indian filmmakers weren’t suffering from lack of resources, rather from a lack of imagination. Ray’s diagnosis was vindicated as it provided directors like Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Tapan Sinha, Adoor Gopal Krishnan and Shyam Benegal an entirely new and unique space to explore. Indian cinema is yet to take a coherent form in the way that French, Japanese and Italian cinema have. However, Ray provided us with a glimpse of the potentialities of Indian cinema and left open possibilities that will no doubt, sooner or later, result in its crystallisation.

The writer is an author, blogger and a student at Jindal School of International Affairs.