Prateek Pattanaik

One of the most fascinating poems in Odia is the 14th-century ‘Kalasa Chautisa’ of Bachha Dasa. Among the oldest extant texts in the language, it presents a farcical picture of the wedding of Shiva and Parvati. Minutes before Parvati’s wedding, her friends come rushing to her chamber — their poor friend is being married off to a terribly antique beggar. They describe to Parvati how horrible her fiancé, whom she has never seen until now, looks like. He has no lineage, not even a penny, not even a proper barber. An old bull sits near him as the ash-smeared pauper coughs uncontrollably.

“You look like his daughter or granddaughter” they say. Poor Parvati bursts into tears. If only she knew all along. She goes to her mother and tells her all this. The queen is surprised; both of them now wail over the father’s decision. Parvati threatens her father to gulp poison if the ceremony is not brought to a halt. How dare he marry her off to such an unworthy fellow?

The entire poem is a great example of slapstick comedy, albeit more than 600 years old. In the villages of Odisha, many folk songs abound with such themes, in which the bride or the groom’s friends prank them by joking about their partners to-be. Though a wedding of gods, the whole ritual is imagined as a very humanised affair. Parvati even accuses her father of selling her off for money, a too-common dynamic in the erstwhile society, where an unwilling girl would be married off to an old merchant by greedy parents. In Sambalpur, famous for its celebrations, families act as parents to both the deities. Betel nuts are offered to other divinities, inviting them to the wedding. There is everything one would expect in a wedding.

Minutes before Parvati’s wedding, her friends come rushing to her chamber — their poor friend is being married off to a terribly antique beggar. They describe to Parvati how horrible her fiancé, whom she has never seen until now, looks like

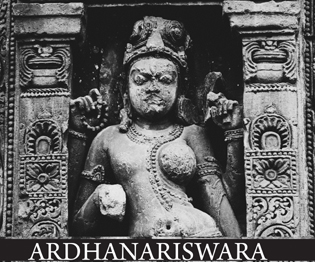

The wedding scene of Shiva and Parvati is common in temples across Odisha. In these sculptures, some over a thousand years old, the couple sit together with a fire in front, while Vishnu offers his sister Parvati’s hand to his friend Shiva. In other friezes, the couple plays dice, or Shiva plays the vina for his wife’s entertainment. In some others, they simply gaze into each other’s eyes. This figure is called Hara-Parbati across Odisha and folk belief advises young lovers to appease them. In medieval poems, Radha prays to Shiva, yearning for Krishna.

Back in the ‘Kalasa Chautisa’, Parvati’s father consoles her to not worry. Her husband-to-be is the god of gods. That consoles the mother-daughter duo. The story ends with Shiva appearing in a handsome form, revealing this was all a joke he had been playing. The rituals are completed and at midnight the newly-wed couple moves around the city seeking blessings from elders. In Puri, about a week later, their friends Jagannatha and Lakshmi are brought together in marriage and then it is their turn to be the guests.

The writer researches and documents vulnerable aspects of Odisha’s culture using technology. e-Mail: pattaprateek@gmail.com