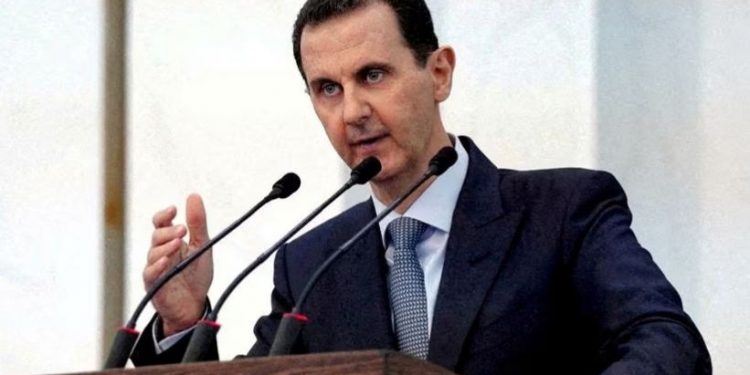

It’s endgame for Bashar al-Assad, who ruled Syria with an iron fist for 24 years, the last 13 years witnessing a bloody civil war, as Damascus fell to rebel forces on 8 December in a lightning-fast offensive. The ousted president has left the country for an undisclosed location hours before the Islamist insurgents entered the Syrian capital. Celebrations erupted across the city with crowds gathering in mosques to pray and young men indulging in celebratory firing. People stormed the presidential palace, tearing apart portraits of Assad even as soldiers and police officers abandoned their posts and fled. The rebels freed the prisoners who had been detained in Syrian jails for years, including the most infamous one at Saydnaya. Described as a “human slaughterhouse,” the Saydnaya prison has witnessed more than 30,000 executions during Assad’s regime. Bashar al-Assad, then an ophthalmologist in London, took the reins from his father Hafez Assad in 2000. Hafez, a career military officer, ruled Syria for nearly three decades, establishing a Soviet-style centralised economy and maintaining strict control over dissent. He promoted a secular ideology, aimed at suppressing sectarian divisions. Hafez forged an alliance with Iran’s Shiite clerical leadership, solidified Syrian dominance over Lebanon, and created a network of Palestinian and Lebanese militant groups. Initially, Bashar appeared to be a stark contrast to his authoritarian father.

However, when protests against his regime erupted in March 2011 at the peak of the Arab Spring revolution, Bashar, a member of the minority Alawite sect, resorted to brutal tactics to quell dissent. He claimed that his regime was more aligned with the needs of its people as he consistently denied the existence of a popular revolt, instead attributing the unrest to “foreign-backed terrorists” attempting to undermine his government. This narrative resonated with many in Syria’s minority communities, including Alawites, Christians, Druze, and Shiites, as well as some Sunnis who feared the rise of Sunni extremists more than they opposed Assad’s authoritarian rule. For years, experts believed that Assad had “won” the Syrian civil war, which has so far killed hundreds of thousands and displaced half of the country’s pre-war population of 23 million, but that assertion is far from accurate. He had only survived the conflict and that was also largely due to the support of Russian airpower and Iranian mercenaries. Assad’s fall is yet another example of how dictatorships, no matter how secular they are, do not last forever. Employing brutal tactics to suppress people and their voices is always a bad idea as, ultimately, it’s the people’s will that reigns supreme. And this is bound to happen everywhere, whether it’s an autocracy or a democracy. At the heart of the recent events in Syria is Abu Mohammed al-Golani, the militant leader whose remarkable insurgency led to Assad’s downfall.

Over the years, he has worked diligently to reshape his public persona, distancing himself from his long-standing connections to terror group al-Qaida. It is pertinent to note here that Golani is a designated terrorist in the US. His insurgent force, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, is going to play a key role in Syria’s next government formation. However, after the five-decade rule of the Assad family, keeping Syria intact could be a Herculean task for any new regime. It is a country of multiple ethnic and religious communities, often set against one another by years of conflict.

Most importantly, many of these groups are apprehensive about the potential rise of Sunni Islamist extremists. The country is also divided among various armed factions, with foreign powers such as Russia, Iran, the US, Turkey, and Israel all having a role to play. Now, with Iran, Russia and Israel preoccupied in other theatres of war and an isolationist Donald Trump returning as the US President, the Syrian people, it is afraid, have been left to fend for themselves.