Holy Ganges begins as a crystal clear river high in the icy Himalayas but pollution and excessive usage transforms it into toxic sludge in places on its journey through burgeoning cities, industrial hubs and past millions of devotees.

The government committed nearly $3 billion of funds to a five-year clean-up of the Ganges, due to be completed in 2020.

The state government in UP has undertaken emergency measures to ensure the water runs clear in Prayagraj during the Kumbh Mela; temporarily closing sewage drains and ordering heavily polluting tanneries upstream to be shut for a three-month period during the festival.

India’s Water Resources Minister Nitin Gadkari said last month the plans to clean the river are on track. Modi too has made the issue a top priority, telling Reuters in an interview last month the government was “working hard” on improving water quality.

But problems still remain. The BJP’s efforts have been hampered by failure to put plans into effect, meaning much of the money has gone unspent. Reuters found last year that only a tenth of the funds had been used in the first two years of the project, with officials struggling to find land for new treatment plants.

November, the United Nations said that the Ganges is still “woefully polluted and efforts to clean it severely lacking”. In a report it said that despite court orders urging state governments along the river to ensure no untreated sewage is dumped in the Ganges, the practice is still widespread. The UN estimates that as much as 80 percent of sewage discharged into two major tributaries that feed the river is still untreated.

This is the story of how it happens.

In the foothills of the Himalayas, the Alaknanda and Bhagirathi rivers converge in the small hill town of Devprayag. This is where the Ganges begins. By the banks of the river, Hindu priests offer prayers and bathe in the icy water.

Hindu devotees bath (top and bottom) and priests perform evening prayers (middle), in Devprayag, India. (REUTERS)

“Mother Ganges”

Pristine waters soon become a distant memory as the 2,525 km-long Ganges snakes its way down to the densely populated plains of north India, eventually forming a huge delta with the Brahmaputra River and emptying into the Bay of Bengal.

The river and its tributaries are a vital water source for hundreds of millions of people, who rely on it to drink, bathe and irrigate land.

At other points along the river, industrial waste and sewage pours in from open drains, turning the river red in some places, while clouds of toxic foam float on the surface in others.

The Ganges originates from the western Himalayas and flows south and east through north India and then enters Bangladesh.

It is Hinduism’s most sacred river and the faithful believe that bathing in the waters can absolve people of their sins.

The Ganges with its many tributaries covering Tibet, Nepal, India and Bangladesh are a vital water source for 400 million people. Most of India’s population can be found in the northern belt around the Ganges.

Monitoring stations set up by the Central Pollution Control Board measure various pollutants along the river. Data from these stations can be seen in the charts below.

Where life meets water

The latest government data shows that in the vast majority of places along the river where water quality is monitored, the levels of human waste in the Ganges mean it is not even safe to bathe in.

A Hindu devotee prepares to take a dip in a polluted canal flowing into the Ganges river during a religious procession in Kolkata, India. (REUTERS)

Human waste

Levels of fecal coliform indicate the amount of sewage in the water. The latest annual figures available show that in 2016, water from 41 of 45 sampling stations that collected coliform data contained in excess of 500 fecal coliform per 100 millilitres, the acceptable limit set by India’s Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB). The average level measured at Howrah-Shibpur, West Bengal, has reached more than 300 times the Indian government’s official limit.

Desirable limits: 500/100ml

Biochemical Oxygen

A measure called biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) is used to gauge “organic pollution”, which is caused by toxic compounds like metals, pesticides and insecticides. A low BOD in water indicates reasonable freedom from these pollutants.

Maximum demand: 3mg/l

India’s CPCB designates that water suitable for outdoor bathing should have a biochemical oxygen demand of 3mg/l or less. Among 56 sampling stations reporting data, 21 have excessive levels of BOD.

Open drains

Between them, homes and factories pump incredible amounts of waste water into the river every day. The most detailed report on how sewage from residential drains and industry pollutes the Ganges was published by India’s CPCB in 2013.

The data can be viewed here https://tmsnrt.rs/2W6hFIr .

The estimate could be conservative. The CPCB currently monitors 161 drains discharging water into the Ganges, it said in its 2018 report on water quality monitoring. Of those, 151 are what it calls “priority drains” – those discharging more than a million litres of water per day.

Untreated sewage flows from an open drain into the Ganges river in Kanpur, India. (REUTERS)

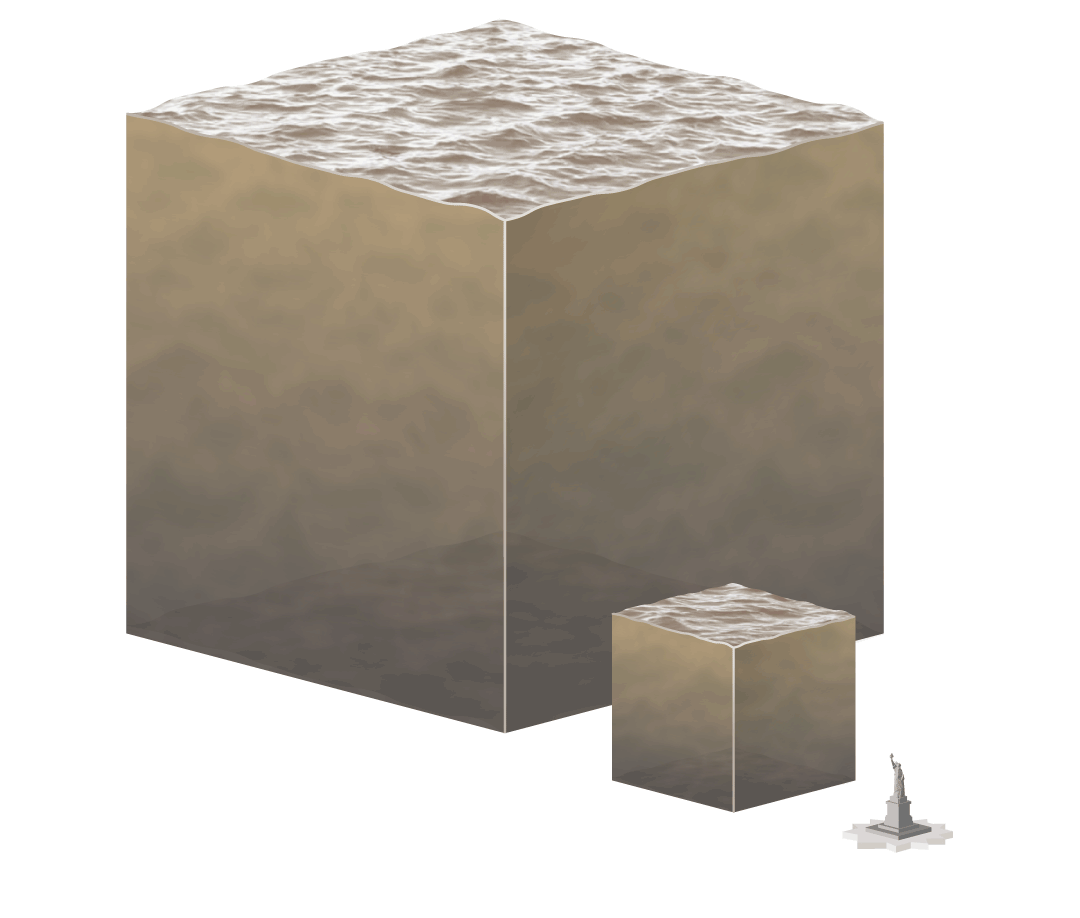

If just one day’s wastewater was pumped into the river was packed into half litre soda bottles, they would stretch to the moon and back nearly four times. If it was formed into a cube, it would be twice the height of the Statue of Liberty.

182 billion litres, Wastewater of 30 days : 6 billion litres, Wastewater of 1 day : Statue of Liberty

Religious impact

For Hindus, the Ganges is personified as the goddess Ganga. Huge religious festivals are held regularly along its banks.

Many believe that drinking the water of the Ganges brings good fortune.

“No one complains after drinking the water,” said Depak Soni, an ayurvedic doctor running a hospital dispensing alternative medicine at the Kumbh Mela in Prayagraj. “I am also drinking it. There are no problems.”

Devotees take a holy dip at Sangam, the confluence of the Ganges, Yamuna and Saraswati rivers, during “Kumbh Mela”, or the Pitcher Festival, in Prayagraj, previously known as Allahabad, India. (REUTERS)

But the 14 ayurvedic hospitals at the festival are treating around 1,000 patients a day, said Suman Kushwaha, a second doctor, with many complaining of dysentery and diarrhoea.

“There are problems with the food here but the water is also one of the causes,” she said.

Elsewhere, millions are cremated alongside the river or their ashes immersed in its waters. The impact of this practice is keenly felt in Varanasi, the ancient and most holy of cities for Hindus.

There, thousands of Indians immerse themselves and idols of their gods every day, believing a dip in the Ganges absolves a lifetime of sins, despite pollution from the tanneries of Kanpur, an industrial city some 300 km upstream. Open drains in the city also add to the problem.

Temples and residential buildings are seen on the banks of the Ganges river in Varanasi (top). People immerse dead bodies in the Ganges river and leave them on the banks of the river prior to cremation in Varanasi (middle). People also sleep on the banks of the Ganges (bottom). (REUTERS)

Religious students practise yoga, pilgrims seek spiritual purification and families cremate their dead by the water’s edge, scattering ashes so that souls go to heaven and escape the cycle of rebirth.

Along the bathing ghats, prayers invoking followers to keep the Ganges clean fill the hot evening air.

Sewage

In many places, India’s antiquated sewage system is unable to handle the huge amounts of waste produced along the river. A 2016 report by the Centre for Science and Environment found that 78% of sewage in India remains untreated.

Untreated sewage from a residential area flows into the Ganges river in Mirzapur, India. (REUTERS)

Over three-quarters of the sewage generated in the towns and cities of India’s crowded northern plains flows untreated into the Ganges, according to a National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) presentation seen by Reuters in 2017, which has not been made public.

In addition, the NMCG presentation showed, about 4.8 billion litres of sewage from 118 towns and cities flows into the Ganges every day. The functioning capacity to treat sewage is only one billion litres per day.

According to official data, the Modi administration has cleared the construction of plants along with the rehabilitation of existing plants with a combined capacity to clean an additional two billion litres per day. That leaves a shortfall of around 1.8 billion litres per day.

State administrations have struggled to find land for new treatment plants, while complex tendering processes have put bidders off pitching for new clean-up projects, officials said.

Industrial pollution

The river is also the destination for waste produced by hundreds of industrial units described by the CPBC as Grossly Polluting Industries (GPI).

A study by India’s water ministry released December 19 said the CPBC had found 961 GPIs along the banks of the Ganges in 2017-18, of which 209 are non-compliant with regulations regarding wastewater.

Employees load buffalo hides in a rolling drum inside a leather tannery at an industrial area in Kanpur, India. (REUTERS)

The problems are striking in Kanpur, near Varanasi. Here, toxic pollution from tanneries flows down slum-lined open sewers, straight into the Ganges. Tannery workers haul chemical-soaked buffalo hides into huge drums. The filthy run-off is dumped in the river.

Sliding under bridges, the water’s colour turns dark gray. Waste pours in from open drains, as clouds of foam float on its surface. At one stretch, the river turns red.

Polluted water in the Ganges river and foam overflowing from a sewage drain connecting the Ganges areseen in Kanpur, India. (REUTERS)

Tanneries make up the largest number of grossly polluting industries by far. They dump a lower volume of water into the river than some other industries, but high levels of toxic chemicals are used in the treatment of the hides. The government maintains its efforts to clean up the river are on course. Water Resources Minister Nitin Gadkari said in December that the Ganges will be 70-80 percent clean within three months and 100 percent clean by March 2020. He did not give details on how the government had arrived at the figures, and did not respond to requests for further comment.

Reuters