Paris: Astronomers Wednesday unveiled the first photo of a black hole, one of the star-devouring monsters scattered throughout the Universe and obscured by impenetrable shields of gravity.

The image of a dark core encircled by a flame-orange halo of white-hot gas and plasma looks like any number of artists’ renderings over the last 30 years.

But this time, it’s the real deal.

Scientists have been puzzling over invisible “dark stars” since the 18th century, but never has one been spied by a telescope, much less photographed.

The supermassive black hole now immortalised by a far-flung network of radio telescopes is 50 million lightyears away in a galaxy known as M87.

“It’s a distance that we could have barely imagined,” Frederic Gueth, an astronomer at France’s National Centre for Scientific Research and co-author of studies detailing the findings, told reporters.

Most speculation had centred on the other candidate targeted by the Event Horizon Telescope – Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the centre of our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

By comparison, Sag A* is 26,000 lightyears from Earth.

Locking down an image of M87’s supermassive black hole at such distance is comparable to photographing a pebble on the Moon.

European Space Agency astrophysicist Paul McNamara called it an “outstanding technical achievement”. It was also a team effort.

“Instead of constructing a giant telescope that would collapse under its own weight, we combined many observatories,” Michael Bremer, an astronomer at the Institute for Millimetric Radio Astronomy (IRAM) in Grenoble, told reporters.

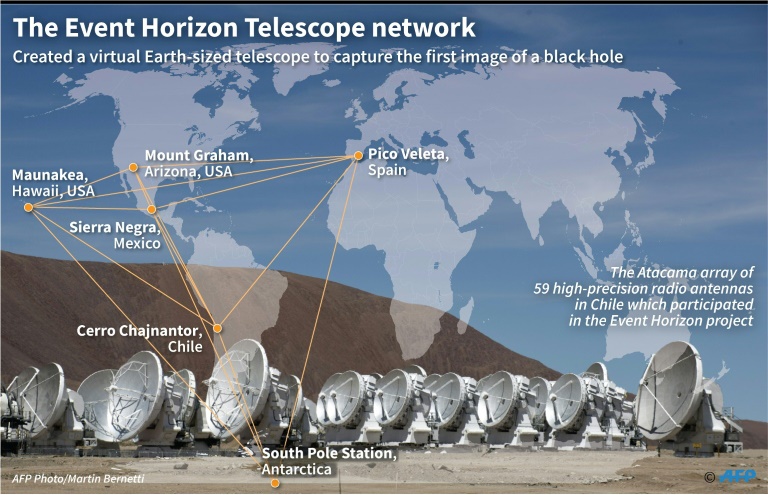

Over several days in April 2017, eight radio telescopes in Hawaii, Arizona, Spain, Mexico, Chile, and the South Pole zeroed in on Sag A* and M87.

Knit together “like fragments of a giant mirror,” in Bremer’s words, they formed a virtual observatory some 12,000 kilometres across – roughly the diameter of Earth. In the end, M87 was more photogenic. Like a fidgety child, Sag A* was too “active” to capture a clear picture, the researchers said.

“The telescope is not looking at the black hole per se, but the material it has captured,” a luminous disk of white-hot gas and plasma known as an accretion disk, said McNamara, who was not part of the team.

“The light from behind the black hole gets bent like a lens.” The unprecedented image – so often imagined in science and science fiction – has been analysed in six studies co-authored by 200 experts from 60-odd institutions and published Wednesday in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“I never thought that I would see a real one in my lifetime,” said CNRS astrophysicist Jean-Pierre Luminet, author in 1979 of the first digital simulation of a black hole.

Coined in the mid-60s by American physicist John Archibald Wheeler, the term “black hole” refers to a point in space where matter is so compressed as to create a gravity field from which even light cannot escape.

The more mass, the bigger the hole. At the same scale of compression, Earth would fit inside a thimble. The Sun would measure a mere six kilometres edge-to-edge.

A successful outcome depended in part on the vagaries of weather during the April 2017 observation period.