SN Misra

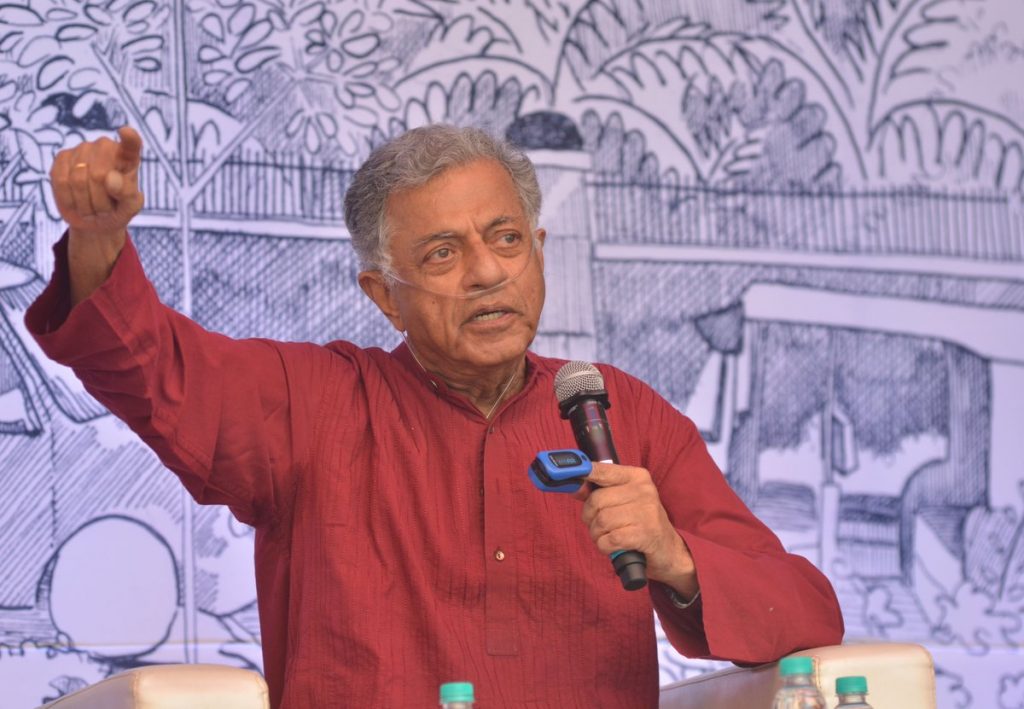

Girish Karnad along with Badal Sarkar in Bengali, Vijay Tendulkar in Marathi and Mohan Rakesh in Hindi produced scripts in the 1960s that remain luminous on stage and celluloid to this day. Although influenced by masters such as Ibsen, Brecht, Beckett and O’Neill, these scriptwriters were strongly rooted in indigenous culture, history and mythology, and tried to showcase their contemporary relevance.

Parallel cinema in India started with Satyajit Ray’s ‘Apu’ trilogy. Girish was an intellectual progenitor of Ray, and cut his academic and artistic teeth at Dharwad, the cultural capital of Karnataka. His father Dr Raghunath Karnad was influenced by the widow remarriage movement of Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar in Bengal and married a widow with a child. Girish was his fourth child.

Girish pursued mathematics and statistics in college and went on to get a first division and a Rhodes scholarship. He went to Oxford with the scholarship, and was elected President of Oxford Union from 1962 to 1963. During this time he sketched TS Eliot and got his autograph. Initially he wanted to write in English and become the Eliot of India. However, the Kannadiga in him prompted him to return to his roots and study the works of Da Ra Bendre, UR Ananthamurthy, Ramakant Joshi and Kuvempu, and adapt them admirably.

He wrote remarkable plays such as ‘Yajati’, ‘Naga-Mandala’, and ‘Tughlaq’. He was also closely involved with India’s parallel cinema in Hindi and acted in the movies of Shyam Benegal such as ‘Nishant’ (1975) and ‘Manthan’ (1976).

The play ‘Tughlaq’ catapulted him to fame; the play portrays how Muhammad bin Tughlaq was ahead of his time, but was impractical. The play was staged at Purana Qila (Old Fort) in Delhi in 1977, and directed by Ebrahim Alkazi, with Manohar Singh playing the role of the visionary king. India was then passing through the Emergency and it was rare sight to see an autocratic Prime Minister such as Indira Gandhi watching the play. Ironically, ‘Tughlaq’ was an allegory of the Nehruvian era, which started with the idealism of Fabian Socialism and ended up with the Hindu rate of growth (3.5 per cent). Girish, the idealist could not have been more caustic in the play. Girish made constant efforts to bring the epics to life, with resounding success.

He was also an intellectual rebel who was always in the news when the communal fabric of the country was sought to be vitiated. He protested against communalisation of Baba Budangiri shrine at Chikmagalur in 2004. He also suggested that the airport at Bangalore be named after Tipu Sultan who he claimed was a visionary and patriot. On the first anniversary of the death of journalist Gouri Lankesh, he wore a placard which read “Me Too Urban Naxal”. He believed in what Harold Joseph Laski had said: “Responsible dissent is the essence of democracy.” He felt a writer must have a strong voice to articulate dissent.

Dharwad, where he spent his youth, saw the unique confluence of Hindustani and Carnatic music. Hindustani musicians from the north performed alongside Carnatic musicians in Dharwad during the winters. But Karnataka today is in trouble with right wing ideology sparring interminably with opportunistic political parties. This used to trouble Girish to no end. He was profoundly influenced by masters of world cinema such as Akira Kurosawa and Ernst Ingmar Bergman. His film, ‘Ondanondu Kaladalli’ (Once Upon a Time), got Shankar Nag the best actor award at the international film festival in Delhi (1977). Girish then paid tributes to the Kurosawa film ‘Seven Samurai’ for the success. He was a cultural icon who could write in the local dialect and could think globally.

Girish was part of an intellectual troika that included Ray and Benegal. They not only promoted India’s pristine indigenous culture with parallel cinema, but also underscored the urgent need to preserve and promote our secular and multilateral cultural character. He was highly influenced by Renaissance of the West and loved Tagore’s poem ‘Where the Mind is Without Fear’. Girish was a true renaissance man; he never lost reason and voiced dissent against populism. His voice cannot be stilled by majoritarian vandalism.

The writer is a theatre buff.