Dr S Saraswathi

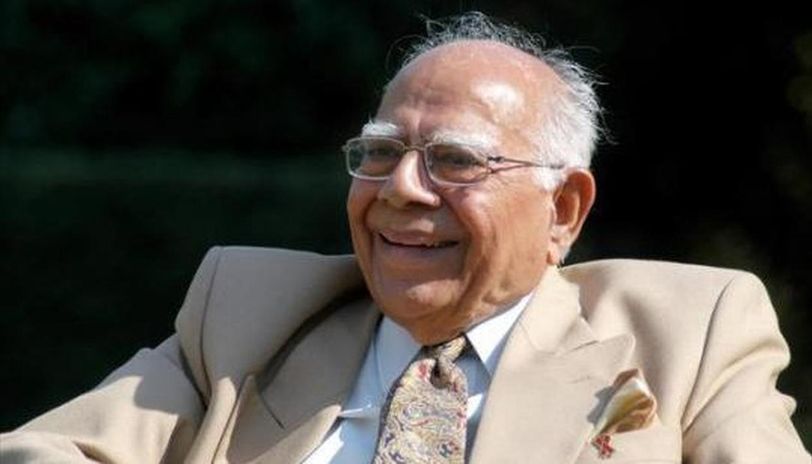

‘The Pros and Cons of Media Trial’ was the topic for the first Ram Jethmalani Memorial Lecture organised in Delhi the other day, in which renowned lawyers participated. At a time when media activism is going strong, it has become necessary to define its place in the rule of law, as the Supreme Court too has stressed this week.

One of the latest additions to most common journalist language is “Trial by Media”. It is generally used as a derogatory term by sections of the society affected by concerned reports, while the neutral public is game with it. Authors, reporters, and performers do not call their product as media trial. Trial by Media is indeed a misnomer for findings of investigative journalism that has grown as a special branch of journalism practised by bold journalists who research on real-life stories. Their task requires absolute commitment to truth and unbiased coverage. The more complicated the crime, the greater is the scope for investigation.

As the general public is curious to follow criminal cases handled by the public and private entities, media picks up such incidents to satisfy their audience. Many of the high-level crimes reflect political divisions. Media trial entered journalism in India in a big way with the Bijal Joshi rape case (2005), followed by the Priyadarshini Mattoo case (2006), the Jessica Lal case (2010) and more recently, the Aarushi murder case.

Investigative journalism is allowed in India. Readers and viewers are by and large thrilled with real life crime stories. The investigator, the facilitator, the publisher, and the sponsor are duty-bound to search and find out the truth. They are accountable for errors, biased reporting, partial coverage, and distorted disclosure. The task calls for a high level of moral responsibility and professional integrity.

Journals and television channels are no longer passive recipients and communicators of incoming newsroom reports. They are not post offices. Today, they are active explorers of truth hidden beneath the visible surface. In this transformation, journalists have become ‘creators’ of news revealing the inside of events and incidents and do not remain mere reporters of what is visible to the naked eye.

Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) launched in 1997 is a global network of reporters and organisations of about 267 investigative journalists probing serious cases of international crimes, corruption, and abuse of power. The most-stunning piece of investigative journalism so far is the Watergate revelations by Woodward and Bernstein (1974) that led to the resignation of the American President, Richard Nixon.

Popular kings in olden days adopted the practice of sending trusted secret agents to mix with people and ascertain what their subjects think and do. Some rulers used to go round their kingdom incognito. In modern free democracies, media’s professed role is to act as people’s agents and take upon the onerous job of unraveling the truth behind complicated crimes.

UN’s basic principles on the Independence of the Judiciary states in Article 6 that the judiciary is required “to ensure that judicial proceedings are conducted fairly and that the right of the parties is respected.” This principle is also in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) which provides that “everyone shall be entitled to fair and public hearing by a competent, independent, and impartial tribunal in the determination of any criminal charge or a suit at law.” ICCPR acknowledges that right to public trial is not absolute and that certain limitations on public access are necessary.

ICCPR also confirms freedom of expression as a fundamental feature of democratic society and includes under it freedom of press. European Convention on Human Rights also admits freedom of press as paramount. However, freedom-loving USA’s Supreme Court has confirmed the potential danger the impact of media could have on trials. This must be due to the continuance of jury system. The increasing tendency to use media when a matter is sub-judice is a subject of discussion among lawyers and laymen in India. In England, the court held that it is important to understand that any other authority cannot usurp the function of the court in a civilized society.

On the other hand, it is a debatable point whether media exposure before court trial can prejudice a case. Courts and judges go by written documents and evidence and, if so, cannot be influenced by media or public reaction. If media investigations expose evidence relevant for a case, it has to be welcomed. Therefore, adherence to truth must be the foundation of media investigation.

The writer is former director, ICSSR, New Delhi. INFA