Alex Hinton

Strange as it is to say, but it is no longer uncommon to hear talk of insurrection, martial law, and civil war in the United States. The arrest of militia leaders in Michigan on charges of planning to kidnap Governor Gretchen Whitmer and incite the overthrow of the state’s government suggests how far far-right politics in America is prepared to go.

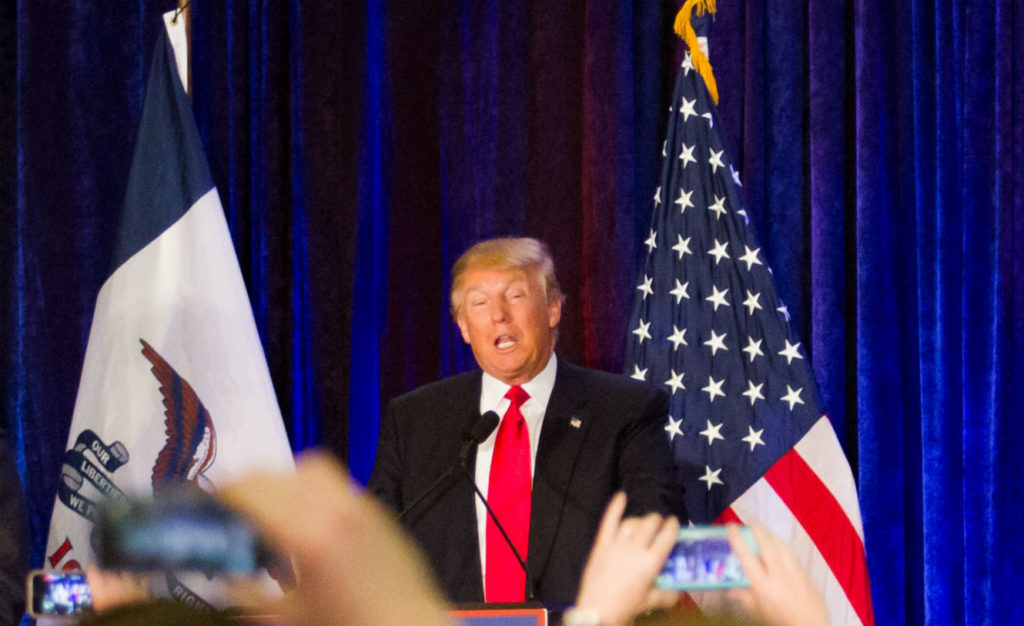

Apocalyptic warnings that next month’s election will descend into crisis are coming hard and fast. US President Donald Trump, now far behind in most polls, will not commit to a peaceful transfer of power. Instead, he encourages white-power militias and extremists, and sows disinformation about everything from mail-in ballots to COVID-19.

While the atmosphere in the US is already alarming, it is worth considering just how bad things could become. There is ample reason to worry that an election-related conflict could devolve into atrocity crimes against black and brown civilians on US soil. As someone who has spent his career studying genocide and mass violence, I fear that the chances of such violence are higher than most people think.

There are six reasons why Americans should prepare for the worst. First, the political, social, and economic situation in the US is deeply unstable. Such instability is a leading factor in all the robust models that researchers have developed over the past few decades to assess the risk of atrocities (including crimes against humanity, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and genocide).

In the atrocity-risk model used by the United Nations, the US checks several boxes: in addition to a runaway pandemic, it is experiencing economic distress, high unemployment, mass protests, natural disasters, and ever-deepening political polarisation. The presence of just one or two of these factors would be alarming enough; the US features more than a half-dozen.

A second risk factor is the country’s history of mass violence and human-rights abuses. Beyond the obvious examples of genocide committed against Native Americans and the enslavement of black people, the US interned Japanese-Americans during World War II and, more recently, engaged in torture as part of its War on Terror. Some argue that the Trump administration’s treatment of undocumented immigrants – including the separation of families – at the southern border constitutes crimes against humanity, and liken US immigrant detention centres to concentration camps.

A third risk factor is the political demonisation that has taken root, particularly on the right, with Trump relentlessly vilifying people of colour. He has referred to Mexicans as ‘rapists,’ Muslims as terrorists, and Latinos as criminal ‘animals.’ He smeared Haiti and all of Africa as ‘shithole countries.’ During the 2018 midterm election, Trump tried to mobilise his base by warning of an immigrant ‘infestation.’ Now, he regularly inveighs against black and brown ‘rioters’ and ‘left-wing radicals’ who are supposedly burning down cities and threatening to invade white suburbs and destroy the American ‘way of life.’

In this context, it certainly is no coincidence that hate crimes have risen dramatically during Trump’s presidency, including instances of violent anti-Semitism. When Trump labelled COVID-19 ‘the China virus’ and ‘kung flu,’ reports of anti-Asian animus surged.

Fourth, by undermining America’s constitutional system of checks and balances, Trump’s presidency has eroded many of the buffers for preventing unrest. Trump openly flaunts the rules, including those meant to curb corruption, and has succeeded in politicising independent agencies from the US Department of Justice to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Trump’s attorney general, William Barr, routinely intervenes on Trump and his cronies’ behalf, and supported the administration’s efforts to deploy federal troops against US citizens. Meanwhile, Trump has pardoned or granted clemency to criminal allies and alleged war criminals.

Such impunity further heightens the risk of violence, by signalling to Trump’s heavily armed followers that anything goes. Indeed, Trump has even voiced support for a 17-year-old gunman charged with murdering two protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

A fifth category of risk comprises catalysts that can make a bad situation worse, including contested elections, marches by armed groups, and other mass protests. Trump has already repeatedly questioned the integrity of the election, suggested that he won’t leave office, and proved eager to use force on civilians. Facing massive, largely peaceful protests, his first instinct was to invoke the Insurrection Act and activate the military.

This summer in Washington, DC, where federal law enforcement has jurisdiction, troops were issued bayonets and deployed to expel peaceful demonstrators from Lafayette Square. In response to nationwide Black Lives Matter marches, Trump’s supporters have taken to warning of sedition, insurrection, martial law, and coup attempts, and armed extremists like the Boogaloo and the Proud Boys have taken to the streets. At the first presidential debate, Trump, prompted to repudiate such groups, instead instructed them to ‘stand back and stand by.’

The sixth factor includes anything that could trigger atrocity crimes in today’s tinderbox political climate. There are many plausible scenarios. For example, Trump’s refusal to accept electoral defeat could spark mass protests (and probably some rioting), creating an ostensible pretext for him to invoke the Insurrection Act and deploy troops against US civilians.

Unrest would undoubtedly spread. Some protesters would respond with violence, prompting US soldiers and federal troops to use even more force. Images of people of colour firing guns would dominate Fox News and Facebook, a leading online disseminator of far-right propaganda that has already been implicated in genocide elsewhere. That would be the trigger: Trump would call for those ‘standing by’ to rise up and crush the black and brown ‘criminals’ and ‘radicals’ he has been demonising. The race war that the mass murderer Charles Manson tried to instigate 51 years ago – he called it ‘Helter Skelter’ – will have been launched by America’s president.

This is just one potential mass-atrocity scenario, but it is not hard to conjure others. Now more than ever, such risk assessments are necessary. By forcing us to consider the worst, they give us time to act. Genocide and mass atrocities have happened all too often, including in America. The question is not whether it could happen here, but whether it can be prevented.

Alex Hinton is Unesco Chair on Genocide Prevention at Rutgers University. ©Project Syndicate