What comes to our mind when we think of Adivasi women? For most of us they are dark-skinned, decrepit and exotic; they live in the jungles and work relentlessly in the fields. The very renowned German historian-cum-philosopher Oswald Spengler once said: “The linear view of history is intellectually dead.” There are barely a handful of texts describing tribal women’s participation in India’s freedom struggle. To analyse the role and participation of women from its onset till recently through a gendered prism is something that is yet to manifest in the paradigm of literary research. The acknowledgement of the struggles of tribal women in mainstream discourse is the need of the hour. It is important that their struggles and their moments of unconditional bravery should be made a part of our collective memories.

The Santhal Hool (revolt) which started in the year 1855 began as a form of protest against the draconian revenue system of the East India Company. There is a lot of literature about both Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu who spearheaded the movement but we would hardly find any history of Tilka Murmu who got killed during this rebellion. It is surprising to observe that there has barely been anything which narrates the huge participation of tribal women during the Santhal rebellion.

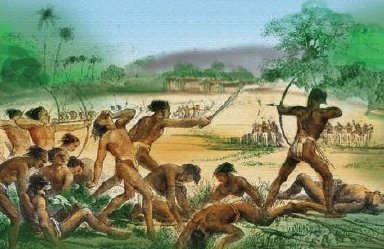

It is important to note that most of the tribal revolutions that emerged during the British Raj were related to the agenda of exploitation and displacement. In fact, we find women leaders outnumbered their male counterparts in some of the most crucial movements during that time. Birsha Munda, during 1895 gave a clarion call for revolution and a large number of women participated in the movement. And one of the most significant contributions of that time was made by Sali, another Adivasi woman. Sali was the most trusted fighter who led the movement with Birsa Munda and fought valiantly against the British. The women fighters used to attach archer tabs around their stomach to disguise themselves as pregnant to smuggle the weapons.

It seems history has been too unkind to record evenly the legacy of the undying spirit of the true patriot, Gurubari Jani. She and her associates came to Puri district of Odisha with a mission to get trained in the art of delivering speeches, organising constructive programmes and martial arts events to fight against the atrocities of the British. Her husband Raidhar Jani accompanied her during her one year and two months training. Once Gurubari Jani’s house was gheraoed by the police as Raidhar remained absconding, busy organising freedom fighters in different regions of Odisha. Having known that the police were marching towards his house he climbed upon a massively branched tree standing on the courtyard of his house. Police failed to trace him and subsequently got vindictive and started intimidating Gurubari Jani. She was mercilessly dragged by the police and stripped half-naked. And that’s not the end; she then was forced and threatened to share about her husband’s whereabouts otherwise she would be put to death and her breasts would be mutilated.

Mungari Oraon, from Oraon tribe is the first Adivasi martyr of Assam. During the 1930s she used to work as a domestic help in the house of a British official. Subsequently, she acted as a spy and started passing confidential information to the Indian National Congress. Mungari got caught amid her secret operation and was killed by her owner. As the Congress was predominantly run by the upper-caste Hindu there were allegations that the tea tribe community was not encouraged enough to participate in the freedom movement. In spite of all these constraints they participated massively.

There were then the Pahariya mutiny in Chota Nagpur region in 1778, the Tanti mutiny in 1786, the Tamar mutiny in 1789, the Sardar mutiny in 1830 which witnessed how the Adivasi women in the frontline fought against colonial rule.

The true meaning of ‘Azadi Ka Amrit Mahostav’ can be justified when our nation acknowledges the legacy of these unsung indigenous heroines who sacrificed their lives to free the country from the British.

The writer is Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Maitreyi College, University of Delhi.