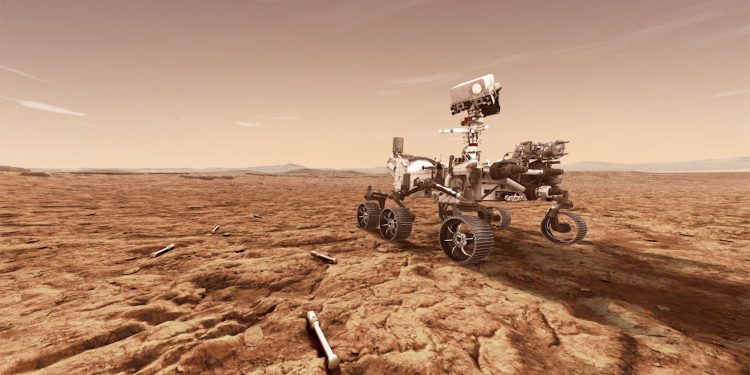

New York: Researchers have revealed that water on Mars, in the form of brines, may not be as widespread as previously thought.

The research team combined data on brine evaporation rates, collected through experiments at the centre’s Mars simulation chamber, with a global weather circulation model of the planet to create planetwide maps of where brines are most likely to be found.

According to the study, published in The Planetary Science Journal, brines are mixtures of water and salts that are more resistant to boiling, freezing and evaporation than pure water.

Finding them has implications for where scientists will look for past or present life on Mars and where humans who eventually travel to the planet could look for water.

“We took all major phase changes of liquids into account — freezing, boiling and evaporation – instead of just a single phase, as has commonly been the approach in the past,” said study author Vincent Chevrier from the University of Arkansas in the US.

“It is looking at all the properties at the same time, instead of one at a time. Then we build maps taking into account all those processes simultaneously,” Chevrier added.

Doing so indicates that previous studies may have overestimated how long brines remain on the surface in the cold, thin and arid Martian atmosphere.

“The most important conclusion is that if you do not take all these processes together, you always overestimate the stability of brines. That is the reality of the situation,” Chevrier said.

Favourable conditions for stable brines on the planet’s surface are most likely to be present in mid-to high-northern latitudes, and in large impact craters in the southern hemisphere, he said. In the shallow subsurface, brines might be present near the equator.

In the best-case scenario, brines could be present for up to 12 hours per day. “Nowhere is any brine stable for an entire day on Mars,” Chevrier noted.

IANS