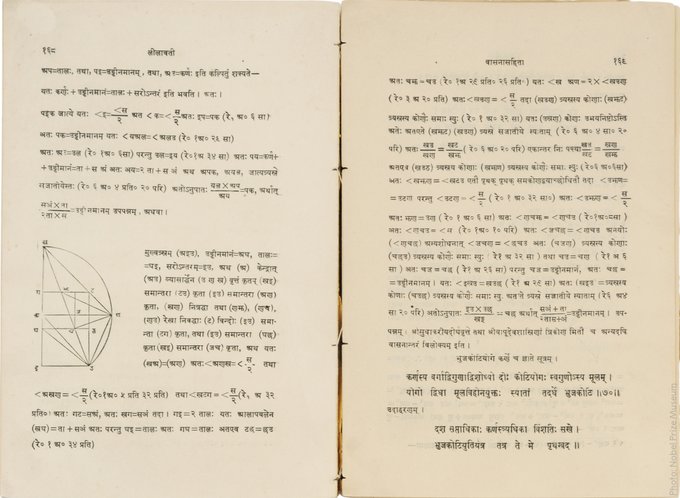

In the season of Nobel Prize declarations, what arouses curiosity is of a Mathematics book studied by Amartya Sen, winner of Nobel in Economics in 1998. The official handle for Nobel Prize shared a picture of Lilavati, a treatise on Mathematics in Sanskrit written in the Year 1150 by Bhaskara ll in the form of a book named after his daughter. A marvel in lessons, theories, and solving mathematical problems, equations and combinations, the book is often cited as an example of the depths to which knowledge in ancient India was pursued. Little attention is paid to such books by the present generations of the academic community. A reason could also be that not many know Sanskrit, a dead language primarily because of its complexity and difficulty for the ordinary person to grasp it. Its learning requires a humongous amount of time and hard work, which, for the new generation may not prove valuable in enhancing skills and abilities.

Sadly in India, researchers, scientists and students of higher studies are rarely encouraged. Education for most Indians culminates in a job where the workload is negligible. It may be because of such an environment that people like Amartya Sen and Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee, among the few Nobel Laureates born in India have their academic and research base now in the West. Indian conditions rarely accord the right climate to such brains to make a mark or prove themselves.