If we blinked, we would have missed the visit of the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi. He was in New Delhi, 24-25 March 2022, meeting his Indian counterpart for three hours and a short meeting with the National Security Adviser. His visit to New Delhi was officially not announced in Beijing nor was he given any importance or serious audience in India. Unlike other dignitaries, Yi was ushered in at the airport through the normal lounge, not through the air-force station. As he happened to be around India, he dropped by New Delhi. All told, can the visit be downplayed as he represents China, which is in the eyes of world community because of its expansionism in its neighbourhood; and is a constant worry for New Delhi for its egregious attitude towards India.

Wang Yi was visiting Islamabad, Kabul and Kathmandu, and decided to have a stopover in New Delhi. Yi went to Kabul to meet the Taliban, including the UN designated terrorist, now the Afghan Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani. He was there, in the wake of the visit of Russian special envoy to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, for a conference next week in Beijing on Afghanistan land neighbours–Iran, Tajikistan, China, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Pakistan. He was in Islamabad to participate in the OIC meeting, wherein he mentioned Kashmir, and was promptly snubbed by New Delhi. His next stop was Kathmandu where he was going to take stock of their mega project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), plus other infrastructure projects.

Why did Wang Yi come to New Delhi? He was not really taking a stopover, as flying from Kabul to Kathmandu is not hours on end. There are a couple of theories doing the rounds. One, he wanted to gauge the Indian mood vis-à-vis the Russia-Ukraine war. Both Beijing and New Delhi, for their respective reasons, have taken similar positions. They have continuously abstained from voting in the UN to name or condemn the Russian invasion.

Second, China would be hosting both the BRICS and RIC summits later this year. Beijing would like Prime Minister Modi to attend both. Likewise, Xi Jinping should be cordially invited to SCO and G-20 meetings which will be hosted by New Delhi next year. Any dilution of BRICS, RIC or SCO will reflect poorly on Beijing as the initiator of such grouping. Beijing will not like these summits to go the SAARC way, become defunct, given the unabating conflict between India and Pakistan.

Be that as it may, the visit was significant, especially after the border stand-off between the two countries since April 2020; Indian soldiers dying in Galwan, and China occupying territories India claims to be hers; the patrolling point 5, Demchock, and Despang. That is not all. China has deployed 60,000 soldiers with missiles, rockets, and mobile airborne support. The stand-off continues spilling over to international forums. New Delhi maintains that there could be no other dialogue than the border disputes, that too, not until, China engages in demobilisation, disagreement and de-escalation. New Delhi fears that if the border stand-off is put on the backburner, it might end up reconciling to China’s salami slicing tactics used from time to time.

In the meantime, New Delhi’s China strategy consists of maintaining diplomatic openness and building capabilities while it puts the onus entirely on Beijing to bring about normalisation of relations. Furthermore, India is suspicious and wary of Chinese intensions. After 15 rounds of border commanders’ talks, and eight rounds of meetings of the special working mechanism for consultation and co-ordination on India-China border affairs, no substantial outcome has been achieved. On the contrary, Beijing has been occasionally sounding out its appetite for more territory. New Delhi has rightly denied Wang Yi to have access to the Prime Minister Modi. It would continue to press for normalisation of relations vis-à-vis the standoff at LAC.

Conversely, China has a different point of view. It would like India to put the border issue at a proper place in bilateral relations. It would rather adopt a three-step strategy on India. One, both the countries should invoke the long-term civilization approach as they have a long and rich civilizational background, at times intersecting with each other’s. The bilateralisms between Beijing and New Delhi should build on their civilizational legacies. Second, both countries should view each other’s development as win-win situation, not win-lose scenario.Third step, both countries should cooperate at multilateral spheres especially those inspired by Beijing– BRICS, RIC, SCO and so on.

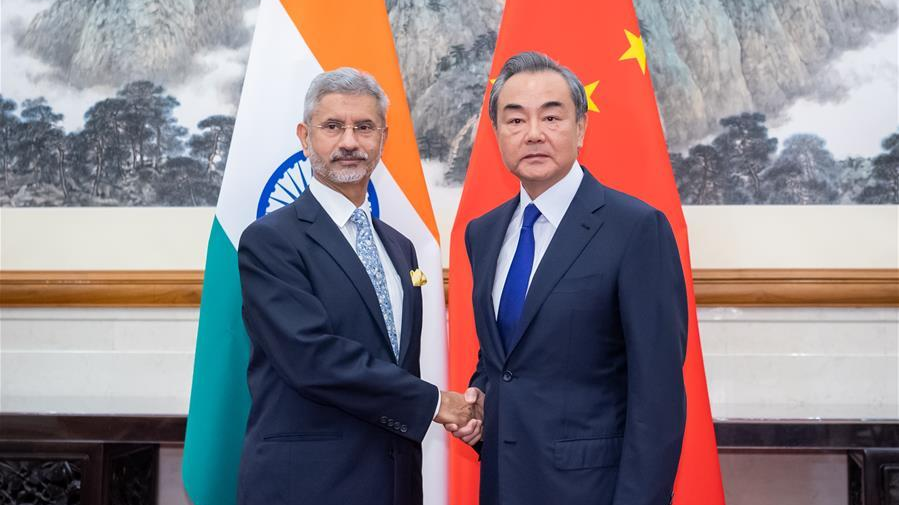

Against such a backdrop, less-publicised meetings of Wang Yi with S Jaishankar and Ajit Doval took place. The meeting with EAM lasted for three hours. What did Wang Yi and S. Jaishankar talk about? As it was anticipated, New Delhi would only reiterate its reservations on Beijing talking about Kashmir, and re-emphasise the urgency of resolving the border disputes. But they did talk about other issues too – trade, visa, Indian students, cooperation on health, Ukraine, Afghanistan and so on. India also raised the staggering trade deficit with China to the tune of $103 billion and the non-tariff barriers China imposes to isolate Indian companies. At any rate, China continues to hold the trade lever.

What is the way forward in India’s bilateralism with China? While New Delhi is building itself and making strategic alliances vis-à-vis China, it is deeply worried about the stand-off and build-up at the border. Beijing considers QUAD, which includes India, as the Asian NATO and grudges India joining the Western bloc.

Wang Yi said India-China should come close. His assertion is that if India and China come on the same page, the entire world will have to notice it. The world cannot ignore the combined strength of India and China. But for that to happen, Beijing needs to have a demilitarised approach, avoid the policy of balance of terror and work towards a synergy between the countries. Certainly, the onus is on China, as the largest economy in the region, to lead in peace, security and co-existence.

In submission, one could say that New Delhi cannot ignore China, but cannot integrate with it. Both India and China should work in good faith and unite to make a better and more promising Asia. Chinese economy is strong, but will its political structure characterised by the dictatorial tendencies of its leader be conducive to Beijing’s leadership role in the region?

The writer is Professor of International Politics, JIMMC. ©INFA