Santosh Kumar Mohapatra

The main argument made by the Union government for the new Parliament building is that the current structure is too old and showing signs of structural corrosion and cannot accommodate rising numbers of representatives in the future. It is true that, in the future, there may be a need for a hall that can accommodate more people’s representatives. But that time is far away. And, the current structure is not in such a bad shape that it needs rest. It can be used for another 50 years with renovation.

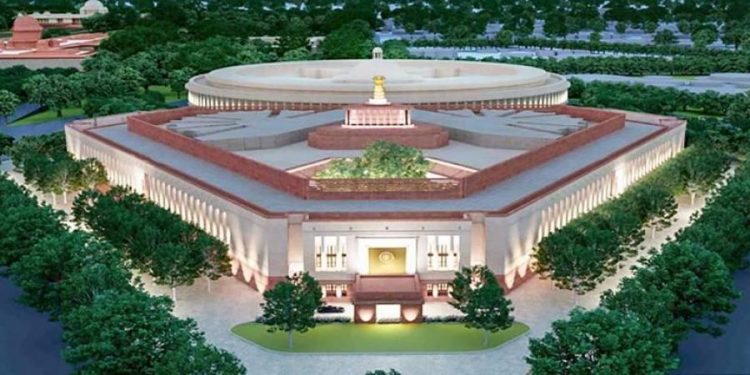

Parliament buildings across the world have become iconic symbols of the countries. Unlike India, many developed countries that can easily afford such costly projects are using much older parliamentary halls or similar halls as symbols of heritage. While their interiors may have been revamped, the facades have remained the same.

The United States Capitol was completed in 1800; the Binnenhof of the Netherlands was built primarily in the 13th century; the Palazzo Madama in Rome was completed in 1505; the Luxembourg Palace at Paris, France was originally built during 1615–1645. Compared to these parliament buildings, India’s Sansad Bhavan is relatively new —the building was completed in 1927.

Many things are being told in support of the construction of the new building such as a sacred venue for strengthening democracy, facilitating Aatmanirbhar Bharat, and enhancing national pride. But certain questions that creep in my mind pertain to the Central Vista project’s timing, hurriedness and the massive cost, and the heritage value of the existing complex. The timing of construction smacks of insensitivity as the project is planned at a time when the economy is crumbling, people are grappling to cope with the pandemic and there is a massive shortage of resources to provide stimulus package to rejuvenate the economy and alleviate the unprecedented sufferings of millions.

Undoubtedly, the new building will provide a congenial space to debate public issues in a collegial manner. But the current one is not much behind in that aspect. And do our legislators need so many comforts when a large number of people are languishing in poverty, starvation, inequality, unemployment and even many have to sleep in streets and pavements.

Further, the vibrancy and strength of democracy does not depend upon how beautiful and luxurious the parliament hall is, but on how much the parliament ensures genuine and qualitative debate, how other pillars of democracy act impartially, how many honest people without any criminal background occupy the seats of the hall, and how people are able to give independent opinions. Just the right to suffrage is not an indicator of the success of a democracy.

In reality, democracy is shrivelling in India as its position is declining in the global democracy index. The world’s biggest democracy slipped 10 places in the 2019 global rankings to 51st place due to “an erosion of civil liberties in the country.” Other pillars of democracy, especially the media, are gradually emasculated. This is reflected in the ‘The Reporters Without Borders’ annual global press freedom index released on April 21. The index has ranked India at 142 among 180 countries. In 2016, India was ranked at 133. There is annihilation of critical thinking, suppression of dissent, hatred is created against dissenters, and media is subverted by veiled threats or allurement of advertisements.

The problems associated with our democracy and the functioning of the government have nothing to do with the structure of the parliament hall. The factors that impede our democracy are failure of the parliament to ensure qualitative debates, ignoring the Opposition while passing bills, lack of discussion on important bills before their passing, and people with criminal backgrounds getting easy entry to the hall as people’s representatives thereby damaging the sanctity of the hall.

The author is an Odisha-based economist and columnist.