Beijing: China, where the coronavirus outbreak emerged two years ago launched a locked-down Winter Olympics Friday. It proudly projected its might on the most global of stages even as some Western governments mounted a diplomatic boycott over the way China treats millions of its own people.

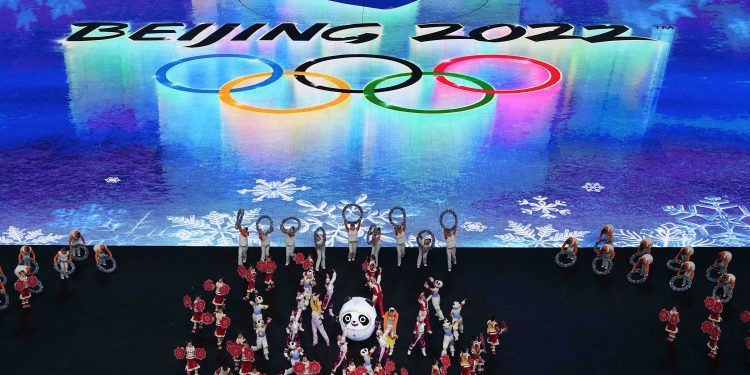

The opening ceremony began just after the arrival of Chinese President Xi Jinping and International Olympic Committee (IOA) President Thomas Bach at the same lattice-encased National Stadium that hosted the inaugural event at the 2008 Olympics.

With the dimming of the lights and a countdown in fireworks, Beijing became the first city to host both Winter and Summer Games. And while some are staying away from the second pandemic Olympics in six months, many other world leaders attended the opening ceremony. Among them the most notable was Russian President Vladimir Putin. He earlier in the day privately met Xi as a dangerous standoff unfolds at Russia’s border with Ukraine.

India announced a diplomatic boycott of the Games after China fielded Qi Fabao, the regimental commander of the People’s Liberation Army, who was injured during the 2020 military face-off with Indian soldiers in the Galwan Valley in eastern Ladakh, as a torchbearer for the event’s Torch Relay.

The Olympics – and the opening ceremony – are always an exercise in performance for the host nation. It is a chance to showcase its culture, define its place in the world, flaunt its best side. That’s something China in particular has been consumed with for decades. But at this year’s Beijing Games, the gulf between performance and reality will be particularly jarring.

Fourteen years ago, a Beijing opening ceremony that featured massive pyrotechnic displays and thousands of card-flipping performers set a new standard of extravagance to start an Olympics that no host since has matched. It was a fitting start to an event often billed as China’s ‘coming out’.

Now, no matter how you view it, China has arrived — but the hope for a more open country that accompanied those first Games has faded.

For Beijing, these Olympics are a confirmation of its status as world player and power. But for many outside China, particularly in the West, they have become a confirmation of the country’s increasingly authoritarian turn.

As if to underline that transformation, the opening ceremony Friday was staged at the same stadium — known as the Bird’s Nest – that held the 2008 version. Back then, Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei consulted on its construction. Now, he is one of the country’s best known dissidents and lives in exile.

Chinese authorities are crushing pro-democracy activism, tightening their control over Hong Kong, becoming more confrontational with Taiwan and interning Muslim Uyghurs in the far west – a crackdown the US Government and others have called genocide.

The pandemic also weighs heavily on this year’s Games, just as it did last summer in Tokyo. More than two years after the first Covid-19 cases were identified in China’s Hubei province, nearly six million human beings have died and hundreds of millions more around the world have been sickened.

The host country itself claims some of the lowest rates of death and illness from the virus, in part because of strict lockdowns imposed by the government aimed at quickly stamping out any outbreaks. Such measures instantly greeted anyone arriving to compete in or attend the Winter Games.

In the lead-up to the Olympics, China’s suppression of dissent was also on display in the controversy surrounding Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai. She disappeared from public view last year after accusing a former Communist Party official of sexual assault. Her accusation was quickly scrubbed from the internet, and discussion of it remains heavily censored.

In the shadow of those political issues, China put on its show. As Xi took his seat, the performers turned toward him and repeatedly bowed. A simultaneous cheer went up from them, and they raised and waved their pom poms toward their president – China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. A barrage of fireworks, including some that spelled out ‘Spring’, announced that the festivities were at hand.

A line of people dressed in costumes representing China’s varied ethnicities passed the national flag to the pole where it was raised – a show of unity that China often puts on as part of its narrative that its wide range of ethnic groups live together in peace and prosperity.

Politics elbowed its way into the proceedings, if gently. The parade of athletes from Taiwan – the island democracy that China says belongs to it – was greeted with a cheer from the crowd, as were the Russian competitors. An over-coated Putin stood and waved at the delegation, nodding crisply as they marched.

The stadium was relatively full – though by no means at capacity – after authorities decided to allow a select group to attend events.

Once the cauldron is lit, as with any Olympics, the attention will shift Saturday – at least partially – from the geopolitical issues of the day to the athletes themselves.

All eyes turn now to whether Alpine skiing superstar Mikaela Shiffrin, who already owns three Olympic medals, can exceed sky-high expectations. How snowboard sensation Shaun White will cap off his Olympic career – and if the sport’s current standard-bearer, Chloe Kim, will wow us again. And whether Russia’s women will sweep the medals in figure skating?

China is pinning its hopes on Eileen Gu, the 18-year-old, American-born freestyle skier who has chosen to compete for her mother’s native country and could win three gold medals.

As they compete, the conditions imposed by Chinese authorities offer a stark contrast to the party atmosphere of the 2008 Games. Some flight attendants, immigration officials and hotel staff have been covered head-to-toe in hazmat gear, masks and goggles. There is a daily testing regimen for all attendees, followed by lengthy quarantines for all those testing positive.

Even so, there is no passing from the Olympic venues through the ever-present cordons of chain-link fence – covered in cheery messages of a ‘shared future together’ – into the city itself, another point of divergence with the 2008 Games.

China itself has also transformed in the years since. Then, it was an emerging global economic force making its biggest leap yet onto the global stage by hosting those Games. Now it is a burgeoning superpower hosting these. Xi, who was the head of the 2008 Olympics, now runs the entire country and has encouraged a personality-driven campaign of adulation.

Gone are the hopeful statements from organisers and Western governments that hosting the Olympics would pressure the ruling Communist Party to clean up what they called its problematic human rights record and to become a more responsible international citizen.

Three decades after its troops crushed massive democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square, killing hundreds and perhaps thousands of Chinese, the government locked up an estimated one million members of minority groups, mostly Muslim Uyghurs from its far-western Xinjiang region, in mass internment camps. The situation has led human rights groups to dub these the ‘Genocide Games’.

China says the camps are ‘vocational training and education centres’ that are part of an anti-terror campaign and have closed. It denies any human rights violations.

Such behaviour was what led leaders of the United States, Britain, Australia and Canada, among others, to impose a diplomatic boycott on these Games, shunning appearances alongside Chinese leadership while allowing their athletes to compete.

Outside the Olympic ‘bubble’ that separates regular Beijingers from Olympians and their entourages, some expressed enthusiasm and pride at the world coming to their doorstep. Zhang Wenquan, a collector of Olympic memorabilia, said Friday that he was excited, but that was tempered by the virus that has changed so much for so many. “I think the effect of the fireworks is going to be much better than it in 2008,” he said. “I actually wanted to go to the venue to watch it. But because of the epidemic, there may be no chance,” he added.