New Delhi: The leaked documents called ‘Xinjiang Papers’ contain six speeches by Chinese President Xi Jinping and other central government figures from 2014, which provide an important link between a wide range of recently-implemented rights-violating policies in Xinjiang and the central government.

The documents were leaked to Uyghur Tribunal and released by Adrian Zenz. This link is further reinforced by the fact that one of the files contains a cover letter from the Xinjiang government from October 2016 that mandates the study of Xi’s top secret April 2014 speeches.

Publicly available evidence, most of which has since been deleted, indicates that in late 2016, these documents as well as the three speeches delivered by Xi, Li Keqiang and Yu Zhengsheng in May 2014 at the Second Central Xinjiang Work Forum, were studied as containing the “strategic deployment of the party’s Central Committee for Xinjiang work”.

Documents collated by Zenz show that local government study sessions of this particular set of speeches aimed to “convey and learn the spirit of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s series of important speeches, arrange and deploy current and future key tasks”.

In late 2016, these “future key tasks” would have referred to the internment campaign, which began in spring 2017. Government reports indicate that in February 2017, just weeks prior to the internment campaign, leading cadres in prefectures and counties were subjected to an intensified study schedule of Xi’s two speeches for at least two hours every week, alongside Chen Quanguo’s own speeches.

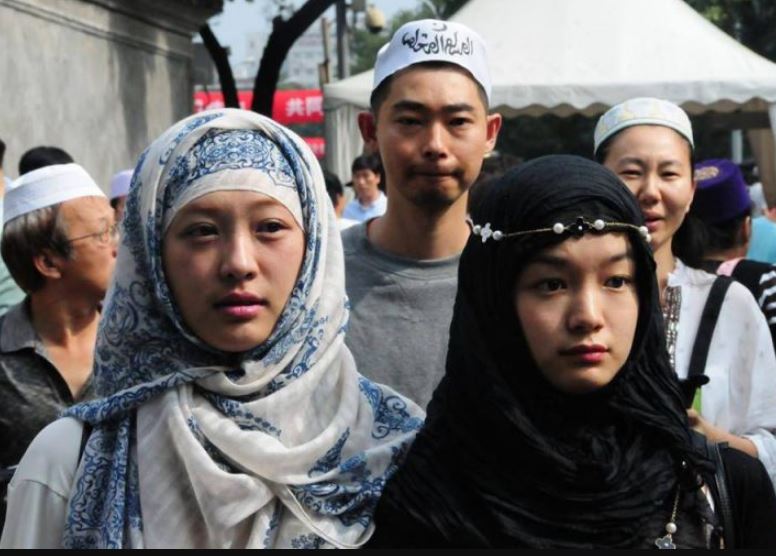

A February 8, 2017 work report from the Yili Prefecture government, a region with a population dominated by ethnic groups, reported a “serious and systematic study” of the speeches delivered by Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang and Yu Zhengsheng at the Second Xinjiang Work Conference in May 2014.

This report emphasises that the spirit of Xi’s speeches must reach every single member of the village work teams. The author had previously argued that the deployment of these teams after Chinese New Year each year determined the timing of the start of the internment campaign, given that these teams constitute a crucial element in identifying those who were sent to the camps.

Second, the files contain four important documents from 2017 and 2018 that directly implicate Xinjiang’s Party Secretary Chen Quanguo and his second in command, Zhu Hailun, in the internment campaign.

Compared to the material from 2014, these documents reflect a much more draconian approach to bring the region’s ethnic groups under control, without any of conciliatory overtones found in the 2014 speeches, Zenz said.

This more recent material contains direct evidence about the importance of the re-education camps and the need to intern substantial shares of the population by “rounding up all who should be rounded up”. In these speeches, Chen Quanguo repeatedly invokes the need to fulfil the will of the central government.

In one instance, he directly states that the “vocational skill education training centres” are an example of the “good methods [adopted by] Xinjiang to fully implement the central goal of the General Secretary [Xi Jinping] for Xinjiang work”.

Chen also states that “the vocational education training centers must be unswervingly operated for a long time”.

The two documents on the punishment of Xinjiang county-level party secretaries who failed to obey government orders show that cadres were expected to ruthlessly carry out whatever order they were given. Among other things, those who failed to “round up all who should be rounded up” faced severe consequences. This evidence further confirms that the responsibility for this atrocity squarely rests with the top-level leadership in both Xinjiang and Beijing.

Finally, the three documents issued by the central government on the “correct” history of Xinjiang, on improving the governance and control of Islam, and on the development of the XPCC in southern Xinjiang confirm the central government’s plans to fundamentally alter the religious and demographic composition in the region (and, in the case of Islam, likely in the entire nation), Zenz said.

Again, this demonstrates how the central government itself is behind the intention to reengineer Xinjiang’s ethnic cultures and communities.

Of particular interest here is also Xi’s statement that “regarding those who violate the law, those who should be seized should be seized, and those who should be sentenced should be sentenced, there must be no one above the law” made in his May 28, 2014 speech, which immediately preceded his remark that Xinjiang could enact that local legislation.

This is because it closely mirrors a statement found in several of Chen Quanguo’s speeches and highlighted in a New York Times article: “Rounding up all who should be rounded up”, Xi’s expression is mirrored word-for-word in a January 2015 government work report by Xinjiang’s Qiemo County.

One might argue that Xi specifically referred to persons who actually violated a law. However, later developments show that Xinjiang’s de-extremification strategy was already turning from a focus on those who had perpetrated acts of violence to preemptively and extrajudicially detain “susceptible” problem populations for re-education purposes.

Given the immediate context of Xi’s words — the statement that Xinjiang could enact its own related legislation, which later became the legal basis for the re-education camps — it is not difficult to see how his call to seize and sentence those who should be seized and sentenced logically evolved into Chen Quanguo’s demand to “rounding up all who should be rounded up” into extrajudicial internment facilities, Zenz said.